Los Angeles-based artist Math Bass, whose current solo show Off the Clock at MoMA PS1 runs through August 31st, 2015, has been carving out a dynamic practice that freely shifts from performance to sculpture to painting to installation, taking up all of the images and objects therein in the same way that one might think of a rotating cast of actors whose appearances stay the same while their characters continue to change from project to project. In other words, outwardly, the works themselves often stay relatively the same, but their behaviors and relationships towards one another continually get redirected and configured. Similarly, Bass’s work traverses one-off and collaborative performances (in which audience members sometimes participate) that involve sculptural sets and props, singular sculptures, interactive architectural installations, and graphic paintings that incorporate her own lexicon of symbols and signs.

While Bass’s practice continues to evolve, it’s an evolution that occurs through conscious recycling and clever interchangeability rather than constantly seeking out the next new thing or drastic change of direction. In this way, previous performances and videos can inform and triangulate a current sculpture or installation, as is the case in Off the Clock, which brings together an array of works formed over the past three years that speak to each other through their shared histories. Each work has stemmed from past performances or previous sculptural projects and now finds themselves repositioned in time and space as well as within the roles that they play in juxtaposition to one another. Off the Clock marks an important and rare example of an exhibition that at the surface seems purely abstract but gradually reveals itself to stand for and interrogate larger questions about perception, language, interchangeability, and perhaps most centrally, where and how the body of the viewer is configured within a given space—not just the space within this show, but space on a much broader and ultimately more intimate level.

To begin, I wanted to talk about the connection between your current work, which is geared towards the creation of environments as exhibitions, and the strong performative impulse that I imagine is still present in your work but was perhaps more at the forefront a few years ago. Do you feel as though performance continues to be a through-line of your practice even if in a more abstracted sense than in the past?

Yeah, that’s true. It’s hard for me to always verbally explain the ways that my work has functioned or changed over time.

I know, I realize this is the case for lots of artists as they choose not to express their ideas in a purely verbal way. But with that in mind, it’s kind of funny because there is also an integration of vocabularies and linguistic symbols that runs throughout your work, particularly in your paintings.

Yes, that is there. I am really interested in language as a structural and psychic tool. It is a physical thing and yet at the same time it is also so ephemeral and in that way it opens up these psychic spaces. I like to find ways that a single sentence or the coupling of a few sentences can pull in two different directions simultaneously, which creates this tension in between those polarities. It is between those two poles that I find that a space can be activated and where the performativity of language occurs. In that sense, the way that both language and performativity gets carried out in my work is that I continue to return to those kinds of tensions.

Installation view, Math Bass: Off the Clock at MoMA PS1, New York, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1. Photograph by Pablo Enriquez.

Is that something that you plan out ahead of time? Sometimes your work appears as if a specific frame or set of borders have been preconceived and then set into motion through other paintings, sculptures, and objects within the exhibition. Is that the case?

I don’t usually approach things from a very premeditated position. I’m never saying to myself beforehand, “If I do this I will achieve this effect.”

That’s interesting because something that I noticed from Off the Clock, and also at your show Lies Inside at Overduin & Co. last year, is that the positioning of the viewer seems as though it is a central concern in the way that both shows were put together. I guess that is not actually how your process unfolds?

I am interested in the way that the position of the body opens up a frame and that depending on where you are in relationship to an object or an image within that space you are opening up different frames while also becoming part of them. So that definitely also has to do with performativity in regards to these installations, though I really don’t even want to call them installations, particularly the work in Off the Clock.

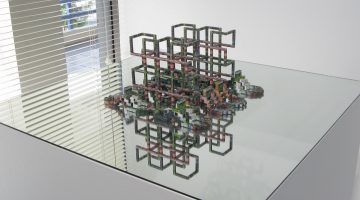

Installation view, Lies Inside at Overduin & Co., New York, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Overduin & Co.

Oh really, why is that?

Well I don’t really feel like it is an installation because everything in it is discrete. I feel like every object or image can function on its own. But maybe I can let go of that idea, maybe the term “installation” doesn’t have to mean that everything has to be supported by each other and therefore always stay together.

I think it is kind of important to make that distinction actually. It seems like people say “installation” to refer to anything that is not a singular work, but technically an installation would mean a set of objects that are meant to be exhibited together in the same or relatively similar configuration.

That also leads into something else that I wanted to ask you about Off the Clock. Can it be seen as a documentary project since a lot of the work has been exhibited previously but in different formats and contexts? Because now there is this culmination of, as you say, “discrete works” that have been shown in the past in fragments and are now all coming together at the same time.

Yes, for this show I pulled from a few different bodies of work. It was a combination of making new work and revisiting older works and remaking them. It ended up being really important to me that I remake certain pieces and sort of go back into them, rather than show the originals. Even though I thought to myself, “Why am I doing this?! I have already made this!” In some instances it was useful for me to return to them and think through them again, and in other cases it was necessary because the originals had been made quickly and were not in the best condition.

So all of the older works at PS1 are actually new versions of their originals?

Not all of them, but some. Others did not need to be remade and some of them had in the past not been used as sculptures but more as performance props or as parts of sets. I am interested in recirculating these works and thinking of them like characters. I have returned to the same sentences that I have used in songs that appear in multiple projects in different ways—they have been in performances, PowerPoints, texts . . . it’s the same idea with the objects that are currently at PS1. For example the cast concrete pants have been used as part of a set that I made for a performance at the Hammer and now they are functioning as singular sculptures in Off the Clock. It’s interesting for me to see how these characters continue to shift and expand in relation to one another as they progress through different formats.

I am wondering if, after selecting certain older works to include in the show and others to recreate, you began making the new works with the intention of responding to your previous works?

I don’t know if I was fully responding to my previous work or more just expanding off of it. For example I made a new piece that looks kind of like two hard-edged dog figures that are connected, which comes from a similar piece that had been two separate dogs. There is also a new version of a piece called Slingbed, which looks like something in between a gurney and a lounge chair that had been used in a performance in the past. I also made new paintings that directly relate to those that were in Lies Inside. With every project it seems like a mad dash and a huge overhaul, and then after the show opens, and I can finally decompress. Afterward, it is hard for me to find an access point into the work. So Off the Clock allowed me to re-enter into a lot of previous work that I felt sort of detached from, which was really nice.

Installation view, Math Bass: Off the Clock at MoMA PS1, New York, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1. Photograph by Pablo Enriquez.

That makes sense. Maybe it was less of a responsive or reflexive approach but more just meditative. Did you make all the new work in New York?

No, most of them I made in my LA studio and shipped to PS1, but I did pour the concrete pants at the museum.

And altogether Off the Clock represents at least three or four years of work, right?

Yes, about three and a half years of my work in different capacities.

Wow! They have functioned in different ways throughout various types of projects over that time and now have finally all been exhibited alongside one another. Does it feel as though they have come to some state of completion or will they continue to be reworked into future projects?

I really like the idea of being able to continue to reconfigure works, though some of course get phased out and then maybe reappear much later and by then have become something totally different but have still stemmed from the same sort of visual or conceptual root of one initial, discrete element.

I am interested in work that is able to function in that way as well, particularly because it can manifest in different ways but continue to ultimately convey the same message. I am still wondering how you see all of these pieces, or characters as you referred to them, now that they have all been shown together. Does that somehow change their meaning for you? Would you be able to do another show like this or is this sort of an end point for their ability to work with one another?

No, I don’t think I would do another show like this. For me this show is this show, and I don’t know what my next will be like. But with this one, it felt sort of like an opening up of everything I’d done over the past few years, and then a closing in a way. Of course, I don’t want to be too definitive about that because I am not totally sure what will happen in the future.

Right. Does it ever gets confusing for you working in this recycling mode? Do you ever start to question the meaning of a particular piece when you are now inserting it into a context that is so different from the one in which it was initially created? Do you ever worry about its legibility as it flows through these various contexts?

You mean is there an aspect of something that becomes almost autoerotic going on?

Yeah, in a way . . . I guess that can be good or bad depending on how you utilize it.

There is definitely that sort of line that you realize exists when you are essentially creating your own language, and that at some point you can potentially go so deep into it that then you start to think, “Wait, this may be illegible to anyone else.”

Is that a concern for you when you think of the viewer?

No, not really.

There is symbology inserted into your work—mainly the paintings—that you must realize viewers are going to make direct references to, like the cigarette, for example, or abstracted letters, steps, or clouds.

Well, some of those symbols that occur within the paintings are more recognizable. I’ve always called that particular image “the cigarette” when thinking about it, even though I wasn’t really trying to depict the actual pictorial representation of a real cigarette. Although, when I first started that series the images were cruder, and the cigarette was much more of a real-looking cigarette. Over time it’s become more formalized and it looks like a shape with a gradient and a plume of smoke. So yes, you can still make the reference to a cigarette, but at other times throughout the series it reads as a column, or a matchstick, or sometimes it becomes more abstract and just looks like any other formal or architectural shape. And in that way it gets used as something that breaks up a plane or gets laid on top of another image in order to disrupt its continuity.

Sometimes everything looks as though it is all on one axis and is contained within a grid and then there is this cigarette or other object that comes into that space that tilts and disrupts the flatness. I did always call that particular image a cigarette, but I have names like that for all of the images or symbols that come into my work.

Really? Even for the things that are much more abstract?

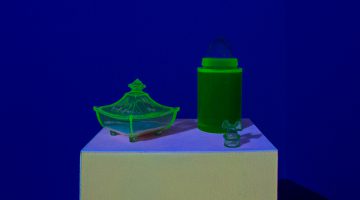

Yes. For example, I had made this amorphous green, tarped object and I always called it “the hedge.”

So do you mainly give those kinds of names just for yourself in order to keep track of them, or do they end up becoming the titles of the works, too?

Sometimes they do. I find titling works to be difficult. Sometimes I just can’t think of anything and don’t want to spend hours trying to come up with something clever. But, at the same time, I do think that titles can be a really effective tool for understanding a work, so I do like coming up with them even though at times it can be agonizing.

I often get a lot out of the title of an artwork. Sometimes I may not have known the name of a work and then when I find out it can really add to or shift my understanding of it. Because of that I am always interested to learn about different artists’ titling processes. Do you usually come up with yours after having made something or can they be a guiding force at the onset?

It depends. Sometimes it can be helpful to start off with one. For example, I did a two-person show with Leidy Churchman at Human Resources in LA in 2013 titled Monte Cristo. It was collaborative in that we were making our own works at the same time and were in constant conversation with each other about them and the show. We had come up with that title at the very beginning, even before either of us had any idea what the work would be. In that instance, as we were making work we were thinking about Monte Christo, and . . .

He seeped in?

Yeah, somehow Monte Cristo came through in both of our works. We each evoked this kind of island that you could really feel within the exhibition. But it doesn’t always work like that. Other times I will have already made something and then all of the sudden the title will pop into my head.

Installation view, Math Bass: Off the Clock at MoMA PS1, New York, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1. Photograph by Pablo Enriquez.

As I am looking at your paintings I see a very formal and even palette-based connection to Fernand Léger. Is that someone that you have considered as a reference? His works are mainly figurative, but I am wondering when it was that you first made this transition from more ephemeral, performance-based work to these very formal, starkly color-contrasted paintings that you have been showing recently?

I’d have to look at his work to see the connection, but generally I’ve incorporated drawing and other 2D work into my practice so it wasn’t really a total shift, although earlier on I did tend to use paint more as a prop. I did a lot of these large text-based paintings on raw canvas. They weren’t stretched so they were more like banners than paintings. They had phrases painted on them like, “Who says you have to be a dead dog?” or, “Who says you have to be an historical dog?” At that time I was working with raw canvas and gesso and using this font that was really just basic shapes that sort of represented letters.

Did those older works on raw canvas also have the same kind of graphic quality as your current paintings?

The graphic, hard-edged aesthetic I use has been pretty continuous, even with my video work. I have been thinking recently about what a symbol is and the way that it can be understood as the ultimate flattening of a referent or signifier, and that through creating a symbol we can flatten and then easily identify and understand something. So I am generally interested in pictorial flattening.

I realized when working with artworks that comment on the Internet, that when information, even if it is not imagery, is flattened or condensed is when it is easiest to manipulate. Even when just writing an email you realize that you need to structure your ideas a certain way, give the overall message certain contours, in order to make it easily digestible for the person receiving it. And we of course see this even more with text messages or tweets. It kind of gets back to our discussion about legibility.

It’s true, I do think a lot about physically compressing in order to expand conceptually or intellectually, and in a lot of ways that is what we are doing all the time with information.

Is condensing an expansive means to an end for you?

I think that using the minimal amount of information necessary in order to convey something is beneficial. Maybe it sounds cheesy but ultimately that is poetry.

Is it a practice that relates to minimalism for you?

I don’t think about it in that way. I just think about it in terms of what the fewest number of elements are that can still activate this work as far as it can go. It’s also important to know when to cut something—when to realize that something just isn’t working and that you need to move on to the next idea or piece. I generally don’t like to have a lot of stuff in my life. I don’t really own a lot of stuff. For a long time I lived in my studio and there was almost nothing in it.

Right, I read about how the wall pieces that create these thresholds or divisions within Off the Clock were directly implanted from the studio to the museum.

Yes, that’s Lauren Davis Fisher’s sculpture. She measured out this nook in my studio and then cut out this shape that is where the staircase goes to the second floor of the building and made the wall-sculpture based on those dimensions. In a way she took this articulated negative space from one site (my studio) and transposed it into the walls of PS1. There is also a video in the show in which you can see the nook with the cutout and the wall that she made in its image, so you can really get a sense of the relationship there. That sculpture fleshed out a space that doesn’t actually exist, so it reads as exposing the interior of this wall from my studio and superimposing one space onto another. That was our collaborative gesture. In one room it is flush with the wall of the museum and in the other room it is pivoted so it is kind of like, as a viewer, you are re-experiencing an environment you just left.

Is this idea of the mirror image or symmetry something that was important for you to run throughout the show?

I do like symmetry but I am mostly interested in the places where something symmetrical suddenly becomes unbalanced. But yes, there are also some paintings in Off the Clock that I think are intentionally mirroring that kind of shift that the wall piece really activates. In some of the paintings one image will repeat and then the whole set will shift and continue on with the same elements.

I think it gives the show a great sense of continuity. I guess my last question is, what you are working on for the future and will it include any of these same themes?

I am working right now on a performance-based piece that will be part of Performa in New York in November, and it will continue to generally take up some of the same issues that I have been addressing in other recent shows.