This is an unusual approach to an interview, in that it is more of a conversation between strangers: one that I staged without having actually been there.

Not only is Kim Anno a painter, photographer, video-maker, activist, mother, and professor, she has also been a mentor and creative inspiration to me for several years, since my time as a graduate student. Ville Kansanen, is a photographer whose work I was recently introduced to by a mutual colleague while directing a media project in the Caribbean. Although the two artists had never worked together, let alone even met each other, I was struck by how much Ville’s images evoked the same prophetic and melancholic qualities that I have come to know in Kim’s work. They both stage the movement of bodies in water, they both work with states of flux, they are both confronting loss and human struggle among unstable shorelines and, as it turns out, they are both based in the Bay Area. I arranged for Kim and Ville to meet up and discuss their respective practices, and provided, from afar, only a few prompts and questions of my own. I wanted to see in which ways their approaches to image-making might echo or deflect one another. Here is the result.

-Lauren Marsden, Contributing Editor, SFAQ

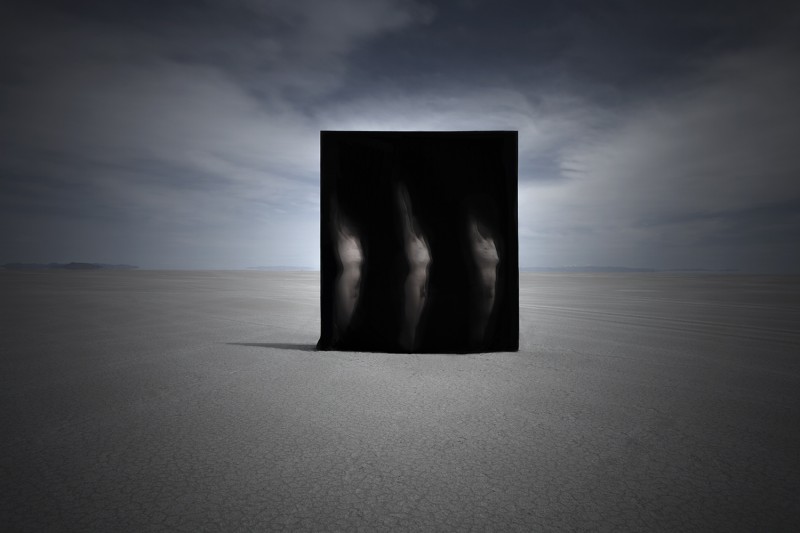

Ville Kansanen. “Death Sheet”– Panamint Valley (Death Valley, CA), 2014, Digital Photograph, 30×20”. Courtesy the artist.

ON THE “UN-SCENIC”

Ville Kansanen: We’re looking at this photograph of Panamint Valley in Death Valley, which used to be an enormous lake. For me, these places are very strange, because I grew up around very fertile lakes. And obviously these are all gone. I can sort of see the lake there, but it’s not there, so it becomes an instant nostalgic landscape for me in a way. It’s capturing a sort of devastation. Obviously, it has implications about our future and how we’re depleting our waters, especially in California.

Kim Anno: The image looks post-apocalyptic: The last human being arrived on the spot where everything has been wiped out. And then this flutter of the image to the black shape is a kind of tension between the memory of a group of people. I’m looking at this other picture of you lying down and this one is really emotional. Is this a salt flat?

Ville Kansanen. “Erasure” – Bonneville Salt Flats, UT 2014, Digital Photograph, 20×30″. Courtesy the artist.

That’s Bonneville. A lot of these are meant to be less literal landscapes. They follow the tradition of surrealists, as an internal landscape, as Roberto Matta called it, “inscapes.” The idea is an erasure, in a way. I’m trying to create this relationship with the landscape, where I almost erase myself and try as much as possible to become a part of it.

…to become a part of the surroundings.

Yeah.

Kim Anno. “Erasing Las Vegas #2,” 2013. Photograph, 22×32”. Shot from the Paris Hotel, Vegas. Courtesy the artist.

This is another thing that crosses my interest too. For some of the pictures that I took in Las Vegas, I take this mirror and various colored gels and then I re-shoot the city as a reflected image. It’s a dissolution of Las Vegas. So, this mirror is a good way to really change something or make something really mutable, like you said, erasing yourself. I was trying to do that in Las Vegas because the un-tenability and disaster of the place is so enormous. What I’m doing is erasing Las Vegas.

I’m thinking about doing a whole series just about Mono Lake. I feel like Mono Lake is a very poetic: an in-between conduit. If you think about it, it has this strange history of being drained for LA water use and then you have this disaster tourism because of the tufa formations that everybody wants to go look at. The only reason you see them is because the water is depleted. They are supposed to be underwater. It’s somewhere between a desert and a lush lake.

Ville Kansanen. “Reclined” – Mono Lake, CA, 2014, Digital Photograph, 30×20″. Courtesy the artist.

It was much worse and then the Save Mono Lake people got the water back into the lake because it was disappearing altogether. I see this one with your white shirt and your black pants on and this is a white collar outfit. That’s something I certainly have been using too and dressing my actors in formal business attire. What was your feeling in that?

This particular photograph stands in for my father. He was an executive at an oil company, but I also feel that the black pants and the white collar shirt is the Everyman uniform in a lot of ways. You could assign almost anything you want to it.

Ville Kansanen. “Father III” – Grant Lake, CA, 2014, Digital Photograph, 30×20″. Courtesy the artist.

In my mind, what I do is try to imagine a future landscape that is fundamentally changed by climate change and that all those consequences are already dealt with and people are still able to have culture and still able to have leisure time in the midst of disaster. I look at models like the Cellist of Sarajevo, who sits in the bombed-out rubble, playing the cello. For me, using popular music, contemporary Classical music, and dancers, is to have people moving in and among the submerged cities or the dried cities. It could be either desert or ocean that’s flooded in. I’m trying to imagine those things without using special effects. I’m not trying to computer-generate it but use analogue ways to suggest it. And you and I were just discussing the use of mirrors and you are using this telescope on your phone.

The Cellist of Sarajevo. Courtesy the Internet.

Yeah. I created this project called The Survey, which was about imagining landing in Death Valley without knowing anything about it. So you are just trying to figure out what the hell it is and what’s going on in it. I use this telescope so you have to really focus on certain things and it also suggests that you are in a machine. Like when you see this underwater footage of those little submersibles and they just have this little porthole and that’s all they see and they have to look around constantly to get an idea of the full landscape.

You’re looking at Death Valley through a telescope on your phone and it looks like the moon or something so there’s a kind of distance mechanism.

Exactly. Especially Death Valley because it has been photographed to death. You see it over and over again in a very specific way: the sublime, surreal landscape. I wanted to disrupt that idea of Death Valley. When you remove all that vastness out of it, it becomes a much more alive and vibrant landscape. We are always trying to find the perfect, beautiful thing to look at. So landscape is really just land, which is segmented into different portions and then you scan it.

Kim Anno. “Ball in Play,” 2013. Medium format photograph 28×42”. From:

Water City: Durban, shot in South Africa. Courtesy the artist.

I totally agree. I’m also looking at the sublime of a landscape and tinkering with it and teasing out the way a human being domesticates the image or tries to capture and control the image. In fact, we want nature at a distance. We really want it in a postcard. We don’t have postcards of the maggots eating the carcasses or the creatures eating the other creatures—the other part of nature that is the un-scenic part. We don’t have pictures of those things, because we don’t want to think about them. We only want to think about nature in its beautiful and sublime qualities.

You said recently in your lecture at SFAI that people love Vegas. I hate Vegas personally.

Even Liberals love Vegas.

It’s the same thing with Mono Lake and the tufas. People love those things and they really represent something terrible: the depletion of something really precious. But people just love it for that. I feel like Vegas has the same thing. And the way society works is that we are all aware of these problems, but we go with it anyway.

We are just passively accepting everything. I don’t want to say that I am clean of that. I’ve also tried to implicate my own participation in that. I try to choose images that I too revere and I try to tinker with the very images that I would want to leave alone.

Kim Anno. “Kids in Retreat,” Water City, Berkeley, 2014. Shot in Alameda Beach. Courtesy the artist.

ON HUMAN SUBJECTS

Who are the people that I work with? I’m really careful to try to work with local people from the areas that I’m working in, so that the impact of climate and issues are on those people, so that it’s not necessarily people flown in from other places, but actual dancers, musicians, singers, and actors from that site, especially young people because they are the architects of what’s to come. They are inheritors of the sins of their fathers.

Most of my work is self-portraiture so it’s me in a way. It’s always a solitary character. Sometimes I’ll multiply myself, which is more of a comment on our multiplicity as human beings, how we experience selfhood, and how we go through life in flux.

Ville Kansanen. “The Procession” – Bonneville Salt Flats, CA, 2014, Digital Photograph, 30×20″. Courtesy the artist.

You were talking about the inscapes or the psychological spaces you make with the figures and there’s a feeling or an acknowledgement of suffering. Like, when one is laying down and the neck is crooked, the mind is trying to console the body. Do you want to talk about that?

I’m trying to deal with my sense of solitude or my sense of loneliness in the world and a lot of this work is from this period when I was severely depressed and was coming out of it. Being depressed is a full body experience. You become really aware of your mind-body relationship and you become very aware that if something hurts in your body, it hurts in your mind. It also tries to deal with a lot of internal suffering.

I admire that. I have not been able to use myself, that’s for sure. I’m much more comfortable being the person who’s on the other side of the camera. I have actually wanted to photograph the images of suffering, but I’ve been swayed by a lot of my participants because many of them don’t want me to portray really bad or suffering scenes. They want to feel hope. So, I have a sense of responsibility, but on the other hand I feel like I do need to present real struggle.

Kim Anno. “Leo and Denise” 2012, from “Men and Women in Water Cities, Chapter One.” Courtesy the artist.

ON BODIES IN/OF WATER

Your work is obviously driven by the issue of climate change. You use water a lot.

I was born and raised in Los Angeles. It’s a beach town and I had a primary relationship with the ocean. My brother always talks about my father being an ocean warrior. I have a lot of desire and empathy for living on the beach and being close to the ocean and also, respect for the vastness of it, and the specter of its threatening dualities with the land and the people.

I think that’s why I connected with the island nations and their challenges around sea level rise. They are relocating people today. In the Maldives, they need to relocate 160,000 people and they are looking for countries to take these people in, because they don’t have any resources on their atolls. So, I had some real feeling about that. This is the beginning of a big thing that we don’t know how to stop. So, we have to figure out how to live in the new world, especially for the coastal communities of which I was raised. So, that’s been really interesting to me to figure out how to image the new coastal life and what can we preserve. I’m interested in intellectual life and leisure, culture and music, and how those things can still be there despite the new disaster.

Kim Anno. “Tea House #3” from “Water City, Berkeley,” 2014. 28×38”. Photograph. Courtesy the artist.

It’s like damage control in a way. Or what the sacrifices are going to be to continue to have a life and still be in this damaged environment. I feel like there is a certain sense of struggle, especially when you have people who have clothing on and they’re in the water, it weighs them down and everything is slower and harder to do.

Esther Williams during the filming of Jupiter’s Darling, 1955

It’s such a technical challenge when I’m shooting. I had to study Esther Williams. I barely understand how she could do this. She has these big tanks that she made these films in. I’d love to go there and shoot. That’s part of the metaphor to me is the clothing in the water is so hard. I’m presenting the obstacles.

There’s this work where I dragged these sheets out into the water. I’m thinking about creating a video piece out of it. I have this fascination with dragging things into water and out of water. It’s something that I’ve been thinking about a lot, as a struggle. I was looking at your work and…

…I had the parachute.

Exactly. That also triggered something in me. For me, the sheets in water represent a feeling of love, but also loss. For me, water a cleansing body. What Finns do is we have saunas next to lakes. That’s how we spend our summers. The tradition of the sauna is that you go in and get really hot and then you go into cold water and you clean yourself. That’s the predominant culture way of how Finns would bathe. It is also a very spiritual thing. Other cultures share this too, like the Native American sweat lodges.

Ville Kansanen. “Thaw” – Mono Lake, CA, 2014, Digital Photograph, 30×20″. Courtesy the artist.

Yes, it’s ceremonial and very important.

But the lake adds this dimension to it. You sweat everything out and then you go in and become refreshed. It’s like being reborn in a lot of ways.

Was bringing the sheets a way of being reborn?

Yes. It’s also a metaphor for fleeting things like happiness and love. A lot of positive emotions for me are momentary. Whereas melancholy, you can always conjure it and bring it back and dwell on it.

Ville Kansanen. “In Absentia” – Owens Lake, CA, 2013, Digital Photograph, 20×30″. Courtesy the artist.

ON LOCATION

I think a lot about the location and it requires a lot of scouting, a lot of looking and thinking and what makes sense to be here. I have three locations for shots coming up and one is in Las Vegas and that will be an ongoing thing. I’m still always looking to figure out how to interact with Las Vegas and its weirdness. The other is Southern Florida and I’m about to shoot in the fall in Key West and work with these Afro-Caribbean dancers and procession people. Key West is completely challenged always by weather and now fundamentally challenged by climate change. The third one is in Crete, in Greece. I’m really interested in that because of the Minoan history there, which was of these ancient people before the Classic period and they actually had a huge civilization. Crete was the center of Western civilization in Europe. It had plumbing and everything, like a huge city. And then it was destroyed by the largest volcanic blast in the history of the planet. And the Minoan people—some of them survived but they eventually died off. So they were really challenged by climate and volcanic activity. There’s something about that that tells us about the days that we’re in and the days to come. That’s why I want to shoot there and work with the young people there.

What do you have next for your locations? Do you go back and forth to the same locations or will you choose new ones?

I go back and forth a lot. Mono Lake, I’ve been there dozens of times. I’ve been there just to bathe there. I’ve been there lots of times and not photographed anything at all. So that’s something that I really love. Finally, I feel at least somewhat of a Dennis Cosgrove—who writes extensively about landscape and geography—he has this concept of an insider, where landscape just stops being a tourist attraction and you sort of are in it and you experience it very differently…and especially Mono, which is very peculiar because it’s a lake, but it behaves like the sea. People have gone boating and disappeared. And that’s pretty unheard of for a lake. You can see the lake from one side to the other but you get these enormous storms. I’m almost a pseudo-local in that area in a lot of ways. It becomes a part of who I am.

Kim Anno. “Men and Women in Water Cities, chapter One,” 2012. Film still, variable size, including 60 feet x18 feet. Courtesy the artist.

The more you go back to a place, the more you understand the placeness of it and the ramifications of human proximity to it and human interaction, you kind of see it more. The first time you go, it’s like you’re sort of a tourist or a voyeur but then as you go back again then, as you say, you develop a relationship and it’s with you and you have a deeper relationship to it. If I got to go back to the Lion preserve in Africa, that would be amazing, because it was such a special place…hearing the roar of lions around you. It’s like a thousand acres and you are wandering around and the lions are all there and you’re with them.

That reminds me of Andy Goldsworthy when you get over this idea of landscape being this beautiful, pastoral thing and I think this applies to almost everything, where you scrape through the first obvious thing and you finally start seeing what it is and how it works. I think getting over that hump and realizing you’re over it is really special. Then, you realize you can make real work in it.