The essence of Lee Mingwei’s art lies in the relationships between people—family, friends, and complete strangers. Many of his works invite the viewer to take part by following simple instructions. Acts like “giving” and “exchange” give rise to a relation centered on something invisible, prompting us to think about “trust” between ourselves and another person. Indeed, Lee insists on not considering people or things as individual, independent entities, calling instead attention to the liminal space where they are intricately interconnected. Many of Lee’s works make us rethink everyday activities like “walking,” “eating,” and “sleeping.” Zen philosophy, which Lee encountered in his childhood, emphasizes being in the “here and now,” rather than being bound by doctrines and theories. It involves questioning our awareness of the minor actions and actual experiences that make up our daily lives. The Taiwan-born artist was in Tokyo for a big retrospective exhibition at the Mori Art Museum, and he was kind enough to share his thoughts on his art practice. Lee’s family history has been linked to Japan since the 1920s when this country ruled over Taiwan, during which time his grandfather studied law at Meiji University in Tokyo while his grandmother learned Western medicine at Tokyo Women’s Medical School.

The essence of my practice is very simple. It’s based on the idea of hospitality and trust, particularly between strangers. When people come to my exhibitions, they get personally involved in my projects. So it’s not just looking at paintings or sculptures or something else you can’t interact with. Many of my projects are based on your kindness and understanding. Without your participation my works are meaningless.

The Mending Project

In the ancient Chinese creation myth, for example, Nüwa is the goddess who mended the sky when it was in danger of collapse. This said, mending for me is also a very personal thing because in Taiwan in the 1960s, the country was very poor so we usually didn’t replace worn-out things with new ones: we used to repair them. This gesture of mending, and the fact that my mother would do it for me, brings me something emotionally satisfying.

When you think about it, cloth is like a second skin for us, and even if you mend something for a stranger, this is a kind of experience that is understood across the border and naturally creates a human bond that transcends cultural barriers. It is about care and giving a gift to somebody. So I was carrying all these feelings and memories and ideas inside myself that were just waiting to be used somehow, and the spark that gave me the final inspiration for the project was 9/11. My friend John’s office was in one of the towers and all 400 of his colleagues died. Luckily for him he was a little late that day and missed the destruction by just a few minutes. When he returned home he collected a few people while walking to 72nd Street. There were so many people out in the street, looking completely lost, so he invited some of them to stay with us. I remember that evening I did two very unusual things: I went to the supermarket and bought all the cakes I could find and I started mending all the pieces of cloth that I always wanted to mend but never found the time to do. It took me eight years to turn this experience into a project. I realized I could do this mending for myself and for strangers. So this is the origin of the Mending Project. When you come to the gallery, you should bring a piece of clothing that you want repaired. You will find me or another person sitting at a table. We will ask your permission to borrow it for the duration of the show because the piece of thread we will use will remain attached to the clothing on one side and the yarn wall on the other . Eventually, all these threads are going to create a big web. This connectivity, or connection with the community, goes back to before 9/11 to when I was a weaver at California College of the Arts. I truly believe that all my projects, and especially this one, are a way to weave human psychology, social relationship, and memory together.

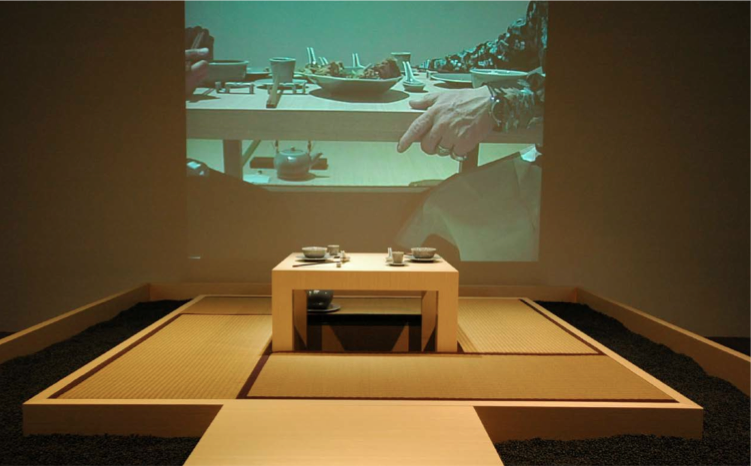

The Dining Project

This project began when I was studying at Yale for my graduate program. When I first arrived I felt kind of lost as I didn’t know anybody. I was both excited and anxious about my new experience. I put out this message all over the campus inviting people to my place in order to have a conversation over a meal. At the end of the day I had about 45 calls on my machine asking me what it was all about. I ended up cooking quite a few meals that year. I think every other day I had someone at my place and my guests were all strangers. It worked this way: I would call these people ask about their dietary preferences, then go to the supermarket to get the fresh ingredients I needed. By the time this person arrived, the meal would be ready and we would share it together. When I moved this experience to a gallery environment, I took something that is familiar and put it into an unusual context that became a frame to re-examine this experience of dining. The way to participate is to fill out a lottery card with your name and phone number so we can contact you. If your card is picked, all you have to do is arrive at the appointed time and be prepared to enjoy the meal. I know that many people are going to ask if this can be called art and this is exactly what I want everybody to do with my work; to start questioning the idea of art itself. There isn’t any documentation as I feel that any would pollute the experience, so it’s a very ephemeral project. But it’s extremely important that it is a one-on-one experience with a stranger. Imagine if I cook a meal for someone I know. The dynamic is going to be quite different.

The Dining Project, 1997. Installation view of Duologue. Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, Taiwan, 2007. Collection of JUT Museum Pre-Opening Office, Taiwan. Photograph by Lee Studio. Courtesy of the Mori Art Museum, Japan.

The Sleeping Project

The seed for this idea came when I was travelling between Paris and Prague after graduating from high school. I was sharing my sleeper-car train compartment with an elderly gentleman, and he was telling me about his family. They were all put into a concentration camp, including him, and after three years, when the survivors were liberated, he was the only one left. He told me about his life in the camp and his relationship with other people who were there. After a while he said he was tired and went to sleep. But I couldn’t sleep at all because of what I’d heard. I’d never heard anything like that. That was the seed of the Sleeping Project. When I conceived the project in 2000, I wanted to create an environment that would be conducive to the same kind of intimacy and human connection I had felt on that train many years before. When installed, I requested that the museum design the sleeping space and the furniture in such a way that the environment would be very comfortable, soothing, and relaxing. One person is chosen, again through a lottery, and invited to share a “bedroom” with me for one night. The person will come around 9:00 pm and, once the gallery door closes, it is interesting to see how two strangers “dance through the night.” Of course, it’s important that there’s no sexual tension in this experience. This experience is not documented, which means the content of the conversations that unfold are not be recorded or made public, but I ask each person in advance to bring something personal that they keep next to their bed; something like the books they are reading or the glass they are using for water, and leave this object with us for the duration of the show.

The Moving Garden

The Moving Garden was originally commissioned for the Lyon Biennale in 2009. It was the first time I went to Lyon. When I travel I often take two books with me: one is Lewis Hyde’s The Gift and the other one is the Japanese classic The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon. I was so fascinated with Hyde’s idea of gift-giving. I think it’s the whole core of my practice. Hyde describes artists as individuals blessed with a gift from heaven who in turn give gifts in the form of experiences that move people. Even before him, the anthropologist Marcel Mauss, who was active from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th, had been interested in the rituals of gift-giving and exchange in ancient civilizations and indigenous cultures that set them apart from the market economies that prioritize competition and profit.

Back in Lyon, I remember sitting and reading The Gift along the Rhône River, and I saw hundreds of flowers coming from upstream. The river was just filled with flowers. This poetic image, along with Hyde’s ideas about gift-giving that I was reading in that moment, gave me the idea for this project. For The Moving Garden set up a very long granite table with a sort of channel in the middle filled with hundreds of fresh flowers. When you leave the venue, I would like you to do two things, for me and for yourself. First, you should make a detour from the museum to your next destination, following a route different from the one you took to arrive. The second and more important thing is that along the detour you give the flower to a complete stranger, as a gift. For me, this is a mutual process. On one side, you are the gift giver. But on the other side, when this person accepts your gift, he or she is giving you a gift as well. In this sense it’s extremely important that you give the flower to a complete stranger. Not your mother, your lover, or your friend, because it would be too easy, but someone you have just met in the street. There is a huge crossing into another realm that you need to do. Imagine: when you have this flower in your hand, you already look different from the rest of the crowd. That flower in your hand gives you a special privilege. Other people are going to perceive you quite differently. Should I give it to this gentleman, or maybe to this young lady? Or this child? This way, by giving the flowers you have received from me to a stranger, each visitor contributes to extending a beautiful chain of gifts across the city.

Fabric of Memory

This project was commissioned by the Liverpool Biennial in 2008, but it was born out of not one but two seeds that were planted in me rather unknowingly. One of them was an image of my mother holding my hand. I was four years old; it was the first day of kindergarten and I didn’t want to go. So my mom made a set of new clothes for me to wear that day and she said, “If you feel sad, think that mom made these clothes for you and it’s like she’s hugging you.” As for the second, years ago I went to see an exhibition of 5000-year-old objects from Xinjiang province in western China, which is more of a Turkish Muslim area. Among the displays there was a piece of a child’s clothing that caught my attention, and the description said that the mother and the child had been buried in the same space. I put these two things together and shaped them into something that could acquire universal meaning. I designed a stage and put a number of boxes on this platform that look like gift packages. Visitors have to take off their shoes, get onto the platform, and open up these boxes that have been wrapped with a ribbon. When you open one of the boxes you’ll find the object and, underneath the lid, the story of both the gift giver and the receiver. Each box is a very private little world that deserves respect created by generous people.

The Letter Writing Project

This project was part of my first museum show at the Whitney in New York in 1998, though it really began with my own experience of writing a letter to my grandmother after she died. She is the person who, more than anybody else, has influenced me spiritually, and in this letter I wrote the feelings of gratitude I wished I had expressed to her before she passed away. The project itself is based on a very simple idea involving letter-writing booths. There are three letter-writing booths. Each one refers to a different posture of meditation in Chinese Buddhist practice: one is standing, one is sitting, and one is kneeling. In each, is paper and pencils with which you can hopefully write a letter of gratitude, forgiveness, or an apology that you were previously not able to express to someone. Once you are finished you have to put it into an envelope that you are free to seal or leave open so that other people can read it. Then you must leave it on the rack inside the booth. You may also want to add the address of the person to whom you have written the letter, in which case we put a stamp on and mail it for you. I’m providing an opportunity to change the relation between you and the letter receiver, but more importantly the relationship between you and yourself.

Guernica in Sand

This project deals mainly with the idea of impermanence. My partner and I took a very long trip to Bolivia, and while we were travelling on a highland desert we were suddenly caught in a sand storm that almost engulfed our car. I then realized that though sand is so small, it comes from huge rocks and is a great medium to talk about impermanence. This project is divided into three stages. In the first stage, people can see this very large sand rendition of Picasso’s painting Guernica. I use this painting and title because it is an iconic painting in Western art history that has so much political weight. There is a tiny area with sand buckets and an unfinished stool. The second phase begins around the seventh week of the exhibition. At sunrise I start working on the unfinished part. Then one person from the audience will be allowed to walk onto the sand painting. You can see the dynamic between the person who is finishing up the work and the person who is walking on it. I try not to define who is making and who is destroying because, in a sense, we are both doing each. After the first person is done, a second person is allowed to walk on the sand, and then a third one, and so on. At the end of the day I stop the person who happens to be walking on the painting at that time. Each of us takes a broom and brushes all the sand toward the middle of the painting. That’s the third and final stage of the project.

This is by far the most performative of all my projects and also a very intense experience for me. The first time I did it in London, when the first person walked on to the sand painting, I could just not stop from crying. It was an emotional experience seeing the painting stepped on after spending all those hours creating the work with my assistants. Then you think about the reason why Picasso originally created this painting; his reaction to the carpet bombing that obliterated the city killing thousands of people in one day.

Guernica in Sand, 2007. Performance view of Impermanence. Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago . Photograph by Anita Kan. Courtesy of the Mori Art Museum, Japan.

The Living Room

This project was originally created for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston after my residency in 1999. Upon receipt, I was invited to go through the Gardner collection so that I could get a few ideas for my project. I was very naïve because I had just started my practice in 1997 after graduating from Yale and this was my first residency. I thought I could go there, come up with a quick idea, and then spend one month playing around, but all I was able to come up with was a half-baked proposal. But they were very kind to me and told me to take my time. Unfortunately, Ms. Gardner wasn’t there at the time, but after one week I noticed that all the people who were working in the museum had all these stories about Ms. Gardner and her collection. I decided to create a living room with a host who would tell people stories about their own collection. For instance, every two days we had a volunteer show his or her personal collection. We all collect things and each of these objects say much about who we are and how we relate to the world. I did this again in Tokyo, though this time around all of the hosts were people who have lived or are still living in Roppongi [the district where the Mori Art Museum is located], and have witnessed how the area has changed and developed, in some cases going back as far as WWII. The collections they showed visitors were made all the more important by their personal memory of things past.