In the mid-1950s, while yet thirteen years old, Henry Martin haunted the Philadelphia Museum of Art, paying special attention to the Walter C. Arensberg Collection, and in particular, the art of Marcel Duchamp. Fifteen years later, he was in Milan, Italy, assisting Arturo Schwartz in the preparation of the monumental monograph, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (Abrams, 1969). Between those seminal years, he attended Maine’s Bowdoin College, schooled by Ray Johnson scholar William S. Wilson; moved to New York, where he befriended Johnson, as well as members of Fluxus; and relocated to Italy on a permanent basis, initially as a university professor, becoming a foreign correspondent for Art International, Art and Artists, Studio International, and Art News. His subsequent career has been just as significant, meeting artists associated with Arte Povera and Nuclear Art, writing the first English monograph on Nouveau Réaliste, Arman (Abrams, 1973), and several books on the artist George Brecht, conducting an essential interview with Ray Johnson, curating a number of important Fluxus exhibitions, and joining the Emily Harvey Foundation board of directors in continuing the late gallerist’s support of contemporary artists, poets and musicians. I interviewed him at the Emily Harvey Gallery (Archivio Emily Harvey) during the course of my residency at the Foundation in Venice, Italy, during November and December 2014.

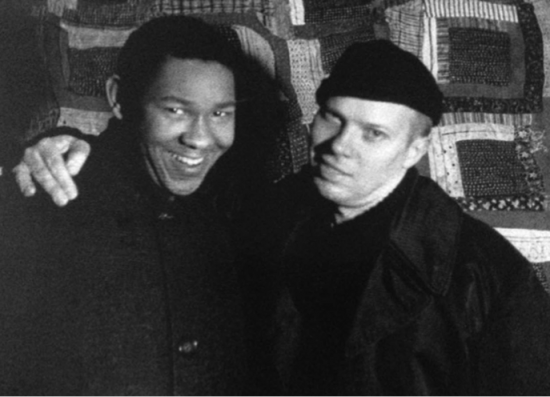

Henry Martin and Ray Johnson. 1964. Photographed by William S. Wilson. Courtesy of William S. Wilson.

You’ve interviewed so many people—Ray Johnson, George Brecht, Francesco Conz, to name a few—but has anyone ever interviewed you?

No, I don’t think so. Oh, yes, a friend named Lea Vergine did an interview with me for Uomo Vogue—“Vogue for Men.” That was very strange. Lea is an Italian art critic. She’s married to Enzo Mari, who is sort of the last remaining prince of Italian design. She’s been a friend for a long time. She did a series of interviews for Uomo Vogue, which became a book called The Last Eccentrics, and I was one of the last eccentrics. I don’t know if I deserved that.

Did that only appear in Italian? Both the magazine article and the book?

Yes, only in Italian.

You mentioned to me previously that you were a student in the 1950s.

I was at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. I was there from 1959 through 1963. In my sophomore year, 1960–1961, I had the enormous good fortune to study Chaucer with Bill Wilson [William S. Wilson, Ray Johnson scholar and collector].

He had come up from New York to teach?

No. He was teaching there at Bowdoin College. Bill taught there for two years. He taught in both my freshman and sophomore years. I don’t know if I knew about Bill, I don’t think I could have. But somehow or another, I saw fit to take his Chaucer course. That was important for very many reasons. Chaucer is the reason I learned Italian. So, that’s sort of a footnote, for Bill was important in many other ways.

Such as?

Well, he was the most intelligent person I had ever met. He was the strangest person I had ever met. How can I put it? He saw a possible strangeness in me, of which he approved. That’s very important if you are nineteen or twenty and don’t know who you are, and have only figured out that most of what the world is doing is of no interest to you and fills you with anguish. Bill was the kind of person who could look at you and more or less say, “I know who you are and what you’re doing, and please keep it up.” That’s the way that Bill came to be so important for me. It was through Bill and his wife Ann, who was even crazier—it was through them that I went to New York when I got out of Bowdoin.

That was 1963?

Yes. Because otherwise, you know, they could have shipped me off to some chic Midwestern graduate school.

Did you grow up in Maine?

No. I’m a native of Pennsylvania. I grew up just outside of Philadelphia. I grew up on the Arensberg Collection, really [laughs].

It was at the Philadelphia Museum of Art at that time?

Oh, yes. It’s been there ever since Arensberg left it. I was thirteen in 1955, so it could have been 1955, because I remember the Arensberg collection from before the time I could drive.

What drew you to that particular collection?

Well, my mother was always taking me to museums, and what interested me most, I think, at that time, was a huge Rubens, Prometheus Bound. I was always very fond of that. Then somehow or another, what first attracted me to the Arensberg collection were the paintings by Dalí. There was one particular painting, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War), 1936, one of those things with beautiful light and battle scenes and bodies all over the place, people dying, and the king in miniature in the middle. There was that, and there were the Brancusis. There was a huge wonderful Mayan calendar—this great big circular stone. And then, there was Duchamp. There were all these weird things there, and it was intensely fascinating.

Henry Martin in the Arensberg Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, circa 1975. Photograph by Berty Skuber. Courtesy of Henry Martin.

Were you drawn to Duchamp at thirteen?

Oh, absolutely. It was very strange. I have no idea why. I wrote a piece about that once for Leggere, an Italian magazine. It’s all about taking the bus to get to Fairmount Park and going to the museum to see the Arensberg Collection. For a while, the great mystery for me was how Duchamp managed to break the Glass [Large Glass, 1915–1923] exactly that way, because it could not have occurred to me at that time that there was anything accidental about anything. So, my question was, how did he manage to break the glass in exactly the way he wanted to? It didn’t occur to me that it could possibly be an accident.

Well, that’s a fantastic background.

It was very strange, because, you know, I was attracted to these things—the Large Glass. I loved the cage with the marble sugar cubes—Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy. There was also a very strange Portrait of Dr. R. Dumouchel. I didn’t know anything about it. I couldn’t make sense of anything at all, but it was a place for me of enormous fascination. There were also the Brancusis, his various versions of Bird in Space. I had no idea of his relationship with Duchamp at the time. I didn’t know anything about it until a little bit later, maybe 1963 or 1965, when I knew Gene Swenson. Gene did this very important exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, in Philadelphia, called The Other Tradition. Gene was another person I met because of Bill. I had gone to New York in 1963 because of Bill. He had already introduced me to Ray Johnson, and through Ray I met Gene, and through Gene, and on and on and on.

I’ve read the first time you met Ray was when you brought some lobsters down from Maine?

That was the lobster trip, yes, in 1961 or 1962 [laughs]. For a long time, he sent me pictures of lobsters. To which I had no idea how to respond, because that was the thing with Ray. Many people don’t really understand Ray, because they always sort of reduce him to the level at which they knew him. Ray was solitary, but he also had enormous capacities, enormous capabilities of empathy. Ray could and would meet you wherever you were. He could fly with the angels and run with the wolves, and do babysitting in between. Ray’s task with me was more like babysitting, I think. I’m not sure.

You lived near each other.

I had an apartment on East 3rd Street. Way over there between Avenue C and Avenue D, right above Houston Street. Ray lived right below Houston Street on Suffolk Street—76 Suffolk Street. We would often meet at the post office. He’d ask me to come meet him at the post office, which was on a square near 6th Street between Avenue A and Avenue B. It was Tompkins Square Park. Ray did one of the pages for his Book about Death of a statue of somebody in Tompkins Square Park—somebody who was dubbed “the postman’s friend.” Samuel somebody. Samuel Cox. I’m amazed that I remember all these things. We would meet at the post office at Tompkins Square, and at the corner of Houston Street and Avenue B. There was a Puerto Rican donut shop there, where we would frequently meet. Ray would take me to places, introduce me to people and things. He was very wonderful in that way. I’ve written about that.

An extremely impressive visit one day—he took me to an eye hospital. He had conjunctivitis. He phoned me up and said, “Henry, let’s go to the eye hospital.” I said, “Sure, Ray.” We took the bus, because the eye hospital was on First Avenue and 14th Street. We took the bus, and Ray was sort of standing erect, his hands in front of him, a cap on his head. There was something strange about him, and I couldn’t tell what it was. Then I realized there was something that Ray was not looking at. It was as though he wasn’t looking at something because he wanted me to look at it. He didn’t want to tell me to look at it. I looked around and there was an advertisement for a bank with a picture of a very distinguished gentleman with grey hair and a grey suit, who had a silver dollar in his eye, like a monocle. I saw that, and for the rest of the day the whole world was all about eye imagery.

It was Ray’s presence, sometimes his attention, sometimes his dis-attention, his instructions—you couldn’t tell. It was impossible to tell, but somehow he turned the whole day into a day of optometry. He was going to the eye hospital, and he was taking me to the eye hospital, and it went on starting in the morning and throughout the afternoon.

We ended up at a Spanish restaurant. There were two restaurants we would go to. One was Il Faro, on East 14th Street, which was Italian, and then there was El Faro, on West 14th Street, and that was Spanish. So, we ended up at El Faro, and Ray ordered paella. They took the cover off this thing, and it was a face with two oysters for eyes. That was how the day ended. The whole day had been like that. That’s the way it could be with Ray. And then, two days later, he brought me a collage, which I still have, of course. And what is the collage? It is not an eye—e-y-e—it is a black paper cut out in the form of an I—“I” as in “me.” That’s the way it was with Ray.

How were you supporting yourself at this time?

I was teaching. I was teaching at P. S. 78 on East 5th Street. First I was in graduate school. I went to graduate school at NYU in 1963-64. I got a master’s degree there in English Literature. But it was becoming ever more clear to me that I was not an academic. That was one of the routes people would have sent me down, but that wasn’t really where I was, and it made me unhappy. So, after my master’s degree, I didn’t want to continue on to a Ph.D. I thought I’d have to, but I really didn’t want to at that time, so I got a job teaching junior high school at P. S. 78. Then there was another one in Bedford-Stuyvesant, and then Italy happened.

How did Italy happen and why?

Italy happened – it’s another Bill Wilson connection. One of my friends at Bowdoin College—a lovely person, David Berry—was from Maine, an old name family. His mother was Priscilla Alden something. There were two boys. Bruce, who was one year older then me, and David, who was three years older. They had a lovely farm in Bowdoinham. Priscilla was Bill’s friend. David was quite special, because he had accidentally shot himself in the arm when he was fourteen or fifteen. He played the mandolin beautifully even though he had very little mobility in his right hand. David had been my classmate in Bill’s Chaucer course. David’s home in Bowdoinham was one of the places we went. David graduated a couple of years before I did.

He reappeared in my mail yesterday, because there is a Maine mail artist who is applying for a residency at the Emily Harvey Foundation, and I wrote back, “Do you know Dave Berry, by any chance?” He replied, “Yes, I do. And if I get the fellowship, Dave will pay me a visit.” David had graduated from Bowdoin, and he had come to Italy. I don’t know why. He taught for two years at the Bocconi University in Milan. At that point, David didn’t want to teach for a living, and he wanted to go to India. That didn’t happen, and he came back to the States to run his farm. David decided he wasn’t going to stay in Italy, so he wrote to me and said, “Henry, one of the things I do here is teach a Chaucer course, and they need somebody who can handle Chaucer and Beowulf at the university in Milan. Would you like to do that?” I was kind of undecided, and I wrote a note to Bill, even though we were both in New York City. I told him that David had suggested that I take his job in Milan. Bill wrote back, “Go, go, go to Italy. Romantics always do.” [Laughs.]

What year was this?

That would have been 1965. I sailed on a boat from New York harbor in August 1965, and came to Italy, landed in Naples, and headed to Milan, because that was where the job was going to be. Meanwhile, I had begun, again at Bill’s suggestion, to write about art, he had suggested that I write an article about his mother’s work. So, by the time I left for Italy I had written about May Wilson and also about Lowell Nesbitt.

Where were they published?

I don’t know why Lowell asked me to write that piece, and I don’t know where, or if, it was published. The piece on May Wilson was a little thing used in a catalog, and it began, “May Wilson has invited us into a crypt to take a look at her doll’s house.” So, I had written about May and written about Lowell, and Gene Swenson at that point had published a couple of articles in a Sicilian magazine called Collage. He told me to send these things to Palermo, so I did just before I left the country. I stayed at an impossible hotel in Rome. I’d been there for a couple of days when a friend who was using the apartment I had left in New York City forwarded me a telegram with an invitation to come to Palermo as the guest of a festival. So, I did. And that’s where I began to meet my Italian friends in the art world.

How long did you stay in Milan?

I was in Milan for four years. I left in 1969. Bocconi University was a private university that was run by the Confindustria—the major association of the great Italian corporations, including Fiat—and the university had two departments, economy/commerce, which they were interested in, and modern languages, which they weren’t. The law in Italy was such that a university had to have two faculties. So, that’s where I was teaching, at the faculty for modern languages. Everything got very hairy in 1968, because the university was occupied by the students. All that was very exciting.

It was especially wonderful, because I was twenty-six by that time. My students were the same age, because things took longer in Europe. They were getting out of high school at nineteen or twenty. University took longer in Europe than it did in the United States. It was a weird situation, because I was, on one hand, faculty, but surrounded by students the same age as myself.

It was a very exciting period, but the reaction of the university to all the student protests was to close down the faculty of modern languages. When that happened, they didn’t fire us, but from that point on staying at the university would have been a question of simply doing examinations to get rid of all the students. I didn’t want to hang around the university to help close it down. At that point, my grandmother had just died, and she had left me a little money. It wasn’t very much, maybe five or six thousand dollars. I said to myself, “Well, why don’t you see if you can live on your typewriter?” and oddly enough, I could.

Who were you writing for?

By then I was writing for Art International, and for Art and Artists, and also for Studio International.

As a foreign correspondent from Italy?

As a correspondent from Milan. I had also written a book about Arman. That was my first book. I did that for Harry Abrams in 1969. That happened because I knew Ileana Sonnabend [among other things, married to Leo Castelli], whom I had met in Palermo, when I first arrived in Italy. In Milan, I was friends with people like [Gian Enzo] Sperone, [Michelangelo] Pistoletto, and all those people who were later Arte Povera. They were connected with Ileana. There’s a connection, and I’m not sure how it worked out, but at one point she asked me to do an article on Arman. I think that’s how it worked out, probably for Art International. Later Harry Abrams was planning to do a book on Arman. Pierre Restany was supposed to do it, but Pierre was utterly unreliable. Pierre would say, “I’m going to do the book,” and then give it to you twenty years later. Arman was tired of waiting for him. Harry Abrams was tired of waiting for him. At a certain point, Arman asked me if I would do the book. So, I did the book. It was the first book on Arman.

Was Arman living in New York or Paris, at that time?

Both. He was in New York and Paris, and also had a house in Vence [France] on the Cote d’Azure.

Were you going back and forth between Milan and New York at this time?

No. The first time I went back to New York was when I was working on the book. I was Milan correspondent for Art and Artists, Art International, Studio International, and maybe even Art News by then. So, it was a possible life. I was also doing a lot of translating. Teaching English had been a great way to learn Italian. It was a possible life. It wasn’t a luxurious life, but it was possible.

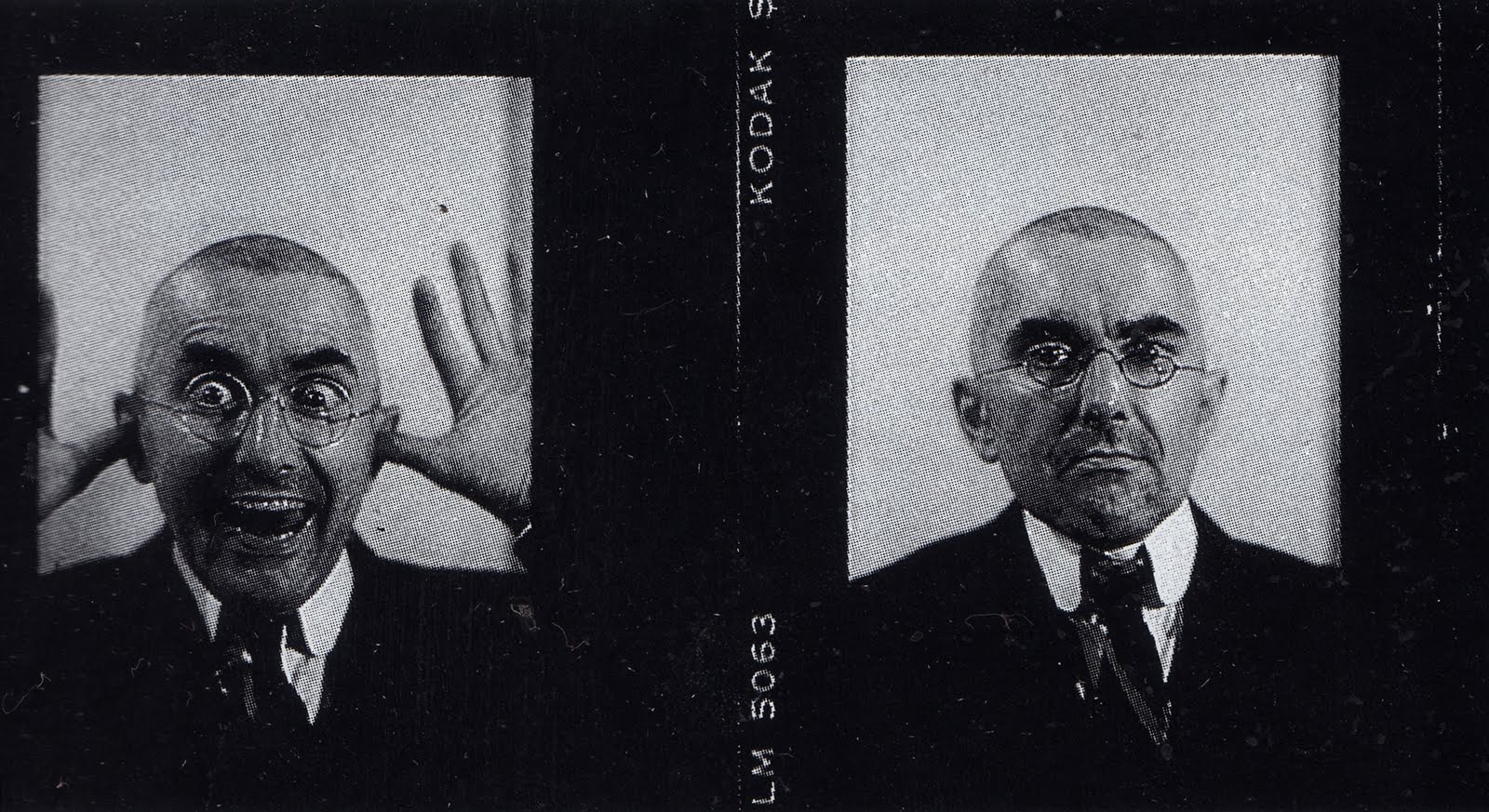

George Maciunas. Courtesy of the Internet.

Maybe I can take you back to those earlier New York years, for I assume being there in 1963, you were exposed to Fluxus.

Ray took me to . . . I’m not sure if it was Ray, but I remember meeting George Maciunas and Henry Flynt. It was at a place downtown, on Canal Street.

You mentioned earlier that Maciunas scared you.

Oh, he frightened me to death. He was a horrible person. First of all, his life was made of his own proselytism. He was a very violent person. He was always colonizing other people’s minds. Which is okay, if the people around you are Dick Higgins, Ben Patterson, Alison Knowles, Philip Corner, or La Monte Young, who were grownups. But you don’t do that to a boy, and that’s what I was. I was just this nice kid—a nice kid that Ray took to places. Ray was the person I needed in my life. I did not need George Maciunas. I mean, he frightened me. During that first visit there was a pair of spectacles that Daniel Spoerri had done. Nails jut forward from the inside surface of the lenses, so to put on the glasses, you would blind yourself. This just occurs to me now, but that’s just the opposite of the story I just told you about Ray. Ray was all about opening people’s eyes—not necessarily, but Ray for me was all about opening my eyes. That visit to Maciunas’s was about the spectacles and blindness. I had no interest in that. I was a very delicate person. I was delicate and open to influence. I had no idea who I was, or what I wanted to be—what was right or wrong for me. I just didn’t need that kind of violence in my life. But you know, Alison was wonderful. Dick was very kind and nice. I met all kinds of people through Ray and Bill.

When did you meet George Brecht?

Oh, that’s a very beautiful story. That again is Ray. That would have been in the spring of 1965. George had already gone to Italy. Ray took me to see a George Brecht show at the Fischbach Gallery. I don’t know what kind of impression it made on me, I couldn’t say now. But it was just the way George was, or how I later learned him to be. Relaxed and contemplative. Very light and very deep at the same time. The acceptance of superficiality. Bill Wilson often talks about surfaces—the metaphorical importance of surfaces, dealing with surfaces of things, not plumbing too deeply. If you plumb too deeply you can lose your own ability to know things. You can grow ignorant of your own stupidity. So, there is that problem there.

When I left New York, Ray gave me a small sealed bottle that contained the water from a New York ice cube, which I was to deliver to George in Rome, so he could transform it into a Roman ice cube. That didn’t work out. George was no longer there. I left the bottle of water with somebody else, to be delivered to him. But it never got to him.

At a certain point, I was working with Arturo Schwarz, because I helped him correct the manuscripts for his book on Duchamp. Arturo is a natural polyglot, but there wasn’t any language that he wrote with absolute certainty. It was very difficult to work with him, because he was very attached to every word he wrote. You had to explain to him, “You cannot say that, Arturo, it can’t be done. It’s not English. It doesn’t work. Tell me what you want to say, and I will say it for you.” I had to work sentence by sentence with him, word by word. I would tell him why a verb had to be where it was. What a direct object was—very cautiously working around this thing that he really believed in, always knowing too that he knew more about it than just about anybody else. George was having a show with Arturo Schwarz, whom I knew quite well because of the intimacy of the work I was doing for him. And Arturo asked me if I’d like to do an interview with George, since Jim Fitzsimmons at Art International had expressed an interest in some such sort of article, or maybe an essay.

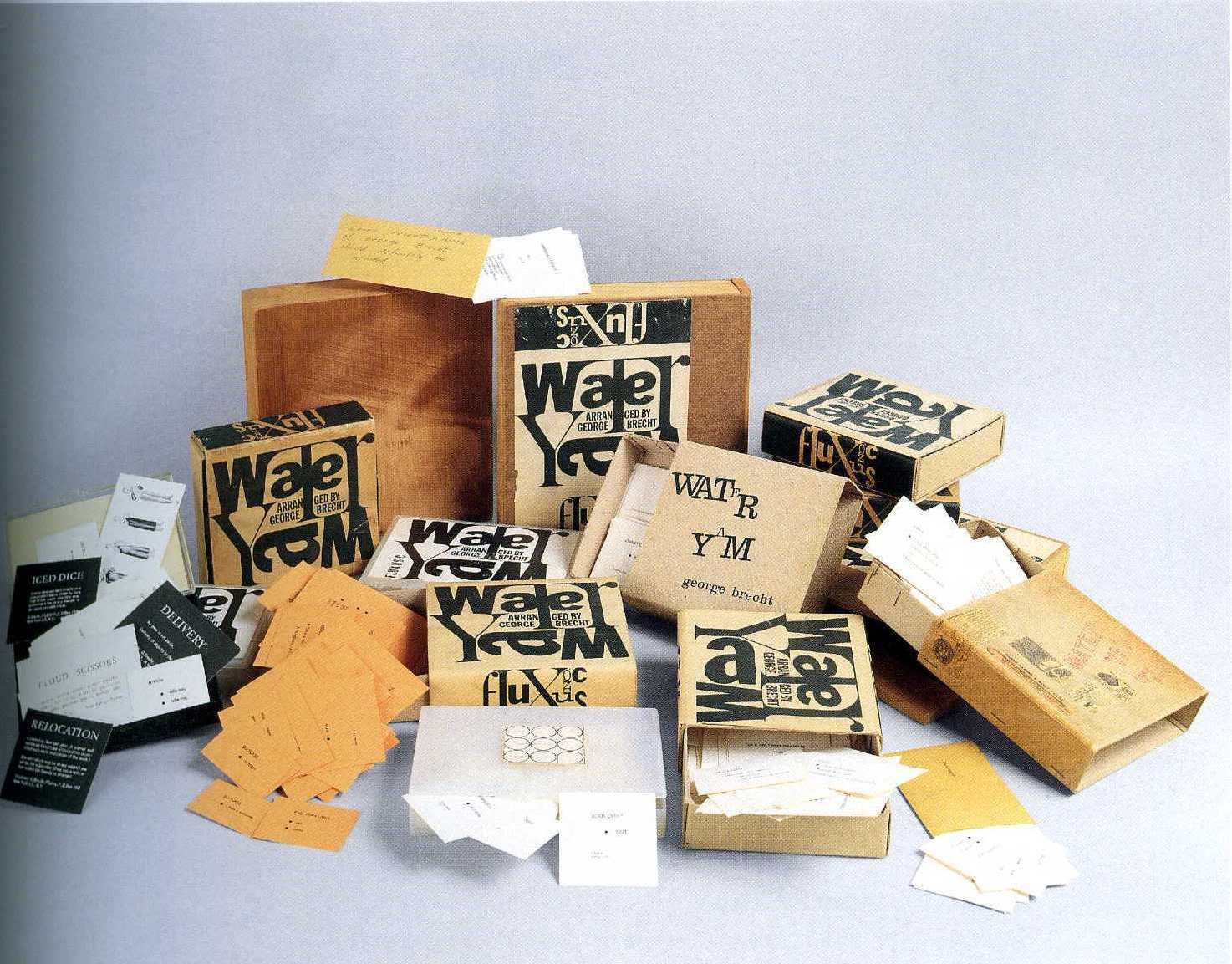

That was the first interview I did with him. It was 1967. That was the beginning of my whole relationship with George, which lasted until the end of his life. A few years after that interview, I did the book for Gino Di Maggio for Mudima Edizioni’s An Introduction to George Brecht’s Book of the Tumbler on Fire. Then there was a second interview when George had a “hetrospective” in Berne. A show called Beyond Events. The title on one of his very first shows, or maybe of one of his early essays, had been Toward Events. By the time of that second interview, I was no longer really an art critic. I could be trusted not to sound like an art critic, by that time.

And what time was that?

By the middle seventies. I was still sort of an art critic, I guess, when I wrote the first book on George, but not all that much. It was a very open book too. I did an essay, republished my first interview with George, but I also republished all the other interviews people had done with George. It was a very open situation. After that, George would turn to me whenever something needed a comment. George would come to me and ask me to write something—like the piece I did on his Event Glasses or the one on his VOID Stones. It was a relationship that lasted until he died [2008].

He was hanging around with the Rutgers crowd—Allan Kaprow, George Segal, Geoffrey Hendricks—but he was a scientist by profession, at that time.

He was a chemist. That’s something he talks about in one of the interviews I did with him. He talked about the way scientists relate to the world in general. George always had this sense of marvel—of wonder—in front of everything. George could look at the shape of an icicle. He wasn’t given to ecstasy, but he was given to looking at things with great wonder—with great wonder. Things asked George questions, let’s put it that way. Always fundamental questions, and like all fundamental questions, as all fundamental questions always do, they bemused him. That’s how that was. What his life had been like in New Jersey, I don’t know. He knew those people, because he was in New Jersey. He was living in New Jersey and working at Johnson and Johnson, and he would have been connected with people who were around him in New Jersey, and people respected George.

George Brecht, Water Yam Editions, 1963-1986. Private collection.

Robert Watts, for instance.He and Bob were good friends. George had an aura. He had been to John Cage’s composition course [The New School for Social Research, 1958]. He was very impressive, because there was no shit about George. There was no fooling around. George was interested in an ultimate font of things. He had a wonderful philosophical mind. He was very much into Oriental thought. It may have been George who introduced me to the I Ching. All these people were sort of playful—Fluxus playfulness. There was an attitude of play there too in George, but there was a fundamental seriousness. People respected that. You couldn’t not respect George. It just wasn’t possible. I don’t know how intimately he connected with other artists.

It was a natural thing to do, but there was also a natural distance. He was in and out of relationships with people. Rather like Ray. George was more solitary, because Ray also had this very frenetic life. Ray knew zillions of people, but basically he was out there alone in Locust Valley. George was basically alone in a wonderful little house he had in Cologne. First he was in the South of France with Robert Filliou. And then he was in Cologne. It was a marvelous house with an attic apartment, which had been built for a painter. There was a huge glass wall with a northern exposure in this bourgeois neighborhood. It looked like a house René Magritte would have lived in.

A Ray Johnson house.

Yes, it was like that.

In the Mail Art world, which is the world I come from, George Brecht and Robert Filliou, and their shop, La Çédille qui Sourit, has gained mythic status, with their development of the concept of an Eternal Network, an international community of artists, cooperating rather than competing.

I knew Filliou, although not tremendously well. But there was also a period when Berty [Skuber, Henry’s wife] and I were often in the South of France, and Robert was living in one of those towns in the Var. We visited him a couple of times, and also saw him at the home of mutual friends. And then there was the wonderful time that Berty and I met him in New York.

When would that have been?

Maybe in 1976, that very first time that Berty and I went to New York together. We met him there quite by chance, on what occasion I don’t remember. It may have been when I did the interview with Ray.

That was in 1982.

No, it couldn’t have been that, because John-Daniel [Henry and Berty’s son] was born in 1978, and Johnny wasn’t there when we ran into Robert in New York. It must have been some earlier trip. It was Robert who sent Berty to her first New York dealer, Jill Kornblee. That’s what happened. He sent her first to . . . I forget who it was, but he was at the beginning of a chain of people which lead to Jill Kornblee. He was very nice. He introduced us to John Gibson, and John Gibson introduced us John Weber, and then John Weber introduced us to Jill Kornblee. That’s how that worked.

Robert was doing a show with John Gibson, and it was a show with cards mounted on music stands. He had come to New York with only one music stand and a little box with cards, but it never occurred to him that music stands in America are very different from music stands in Europe. Music stands in Europe have a clip on one side. But not in America.

I remember with Berty, we walked all over New York City with Robert trying to get him the music stands he needed. He thought it would be the easiest thing in the world, but it ended up that he had to have fifty music stands flown in from Paris, or somebody did it for him. So. Berty and I were running around the city with Robert trying to find music stands, and it was then he introduced us to these other people. But the Eternal Network. I don’t know. I don’t think it had anything to do with networking with other people. It wasn’t like a mail art network, or anything like that, at all.

Although Filliou did go to Vancouver and mixed with the Western Front, and a newly emerging mail art network that was a presence there.

His notion of the Eternal Network was very open to everything and anything, but I don’t know if he had a sociological idea, as far as I can tell. The Eternal Network was one of those ideas like the Genial Republic. It was an imaginary place in which he lived. Like his concept of the Principal of Equivalence—well made, badly-made, not-made, were all the same thing. To make sense of these ideas you have to realize he was a Tibetan monk. He told me a wonderful story about a meeting with one of his Tibetan teachers. Robert had said something about the tremendous difference between the East and the West to his Tibetan teacher. The teacher responded, “It’s not really all that different, because after all, you people in the West think that television is life, and we believe that life is television.” [Laughs.]

When did you and Berty move to Bolzano [South Tyrol, Northern Italy]?

We didn’t move to Bolzano. She is from that area. Bolzano is up on the road that goes from Verona to Munich. It’s a German-speaking area. Bolzano, the capital of the Province, is about fifty miles south of the Brenner Pass. After Milan, I was in Rome for a while. In Rome, I was working on a book. A little book published by Gino DiMaggio. The subject of the book was Gianfranco Baruchello and his work. I created a kind of a dictionary of the cardinal images in Baruchello’s work. It’s called Fragments of a Possible Apocalypse. I worked on that throughout a spring and summer in Rome.

At that point, I had had enough of Rome. It was an art world life in Rome. That was the attraction of Rome, and I didn’t find that attractive at all. So, I asked for help from a friend, who has remained a very good friend. He’s our oldest friend in Italy, from Bolzano. He’d been a student of mine at Bocconi University. I asked him to find me a place up in the mountains, because that’s where he was from. The idea was to spend the winter there and to write a book and ski. It was in the course of this that Berty and I met though another artist friend. I guess we must have met in 1970 or 1971, because I left the university in 1969, and I was in Rome briefly. I moved to the Bolzano area—to the village of Fié allo Sciliar—in 1971, and met Berty shortly after.

You did a Ray Johnson show with the Arturo Schwarz Gallery in Milan in 1972, Evaporations by Ray Johnson.

It wasn’t the Evaporations show. Ray may have done the Evaporations show with Arturo. I think he had two shows with Arturo. I’m not sure, but one show was his Potato Mashers show. Arturo, Ray, or both, asked me if I would write the essay for the catalog. So, that’s what I did.

So, you moved up to Northern Italy, and you met Berty in Bolzano.

We were both friends with an artist named Sergio Dangelo. Danglelo was famous for Nuclear Art. Dangelo was a friend of Berty’s, and my last apartment in Milan had been just above his studio. One day when I had to go down from Fié to Bolzano, I ran into another friend who just happened to mention that Sergio would be in Bolzano on the following evening for a small show. So, I went to the show, and Sergio said, “Well, now that you’ve come to my show, I also want you to see the show of my friend, Berty Skuber.” That was the occasion when Berty and I first met.

You’ve been living in the mountains above Bolzano ever since?

I came to Italy to take a two-year teaching stint as a junior professor, and I stayed in Italy the rest of my life. In 1971 or 1972 I went to a small town in Southern Tyrol intending to stay a winter, and now I’ve been there for forty years. Johnny was born in 1978. We live in a fabulous place. It can’t be believed. Farms up there are not that large by American standards, but it’s in the mountains, and we rent an old farmhouse. The farmer is fifty meters up the hill behind us. We don’t see their house, but it’s a presence. Aside from them, we don’t see another house, aside from a group of houses on the other side of the valley. We see them directly across the valley, but to get to them from where we live would be an hour’s trip by car. The place where we live is perfectly isolated.

You’ve curated shows in the area.

Yes and no. I’ve never done anything professionally that was serious or constant. My one constant has been as a translator. It’s part of me. I’m good at languages. I don’t have a lot of imagination, so I use other people’s imagination. That’s what a translator does—he’s a language expert at the service of other people’s imagination. I’ve only curated two or three shows, ever. And always only because somebody asked me to do it.

The first time I did it, there was a show of American graphics at a local museum, and I’m an American and an art critic, so they asked me to do that, and I did it. This also put us more closely in touch with a wonderful man—later the first director of the new Bolzano Museion—named Piero Siena. Piero was very much like my father: very handsome, very urbane, beautifully dressed and always soft-spoken. Women adored him, and he also had a kind of attentive reserve.

What did your father do?

My father ran a type of laundry business. He had concessions in nightclubs, personnel for parking lots, hatchecks, restrooms. He also did this for racetracks in Philadelphia and New Jersey, and also in Florida. He had the concessions for the two main racetracks in New Jersey. One was in the south in Atlantic City, and the other was in the north in Monmouth. I don’t know where I’m getting these words from. You’re bringing back memories I didn’t know I had. In Florida, he did the concessions for Hialeah.

There was a point at which Piero said, “Do you want to do a Fluxus show? You know all these people. Why don’t you do it?” I did, and it was a fabulous show [Museo d’Arte Moderna, Bolzano, 1992]. The point of the show was that I didn’t call it “Fluxus.” I called it “Fluxers,” remembering too that George Brecht always said, “Fluxus was Maciunas.” With Maciunas gone, there was nothing left. The Fluxus group for George Brecht was like a man walking his dog in one direction, a lady walking her dog in another direction, the dogs stop and sniff for a while, and it’s over and done with.

I’ve always felt that if there is anything to be said about these people, it’s because each of them has an independent life. They are not defined by their relationship to each other. I mean, Philip [Corner] is a musician, and he does the things he does. Alison [Knowles] is Alison. Geoffrey [Hendricks] is Geoffrey. George [Brecht] is George.

It was a great show at the museum in Bolzano. It was great because they had eight large rooms and a huge central room. In the central room, I borrowed the Fluxus collection of Ken Friedman from the Henie Onstad Art Centre in Oslo, Norway. Each of the other rooms showed major works or groups of works by only two or at most three artists. There was a beautiful piece by Alison Knowles, which was a clay circle on the floor with objects on it.

There were both historical works from the Friedman Collection, and newer works?

The other stuff is work they did there. There was a beautiful room with works by Alison and George, and a big installation by Geoffrey. Joe Jones too had a beautiful group of works. Joe died on the day before the show closed. It was a Saturday, and Ben Patterson or Michael Berger phoned us that he had died. On Sunday morning, Berty and I went down to the Museum and turned on all of Joe’s music machines, and let them run until the batteries died. That was our tribute to Joe.

Have you given your papers to this same museum?

No. My Ray Johnson papers have gone to MUMOK (Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien) in Vienna. It’s a museum of modern and contemporary art.

Why did you decide to deposit them there?

They were interested. Berty is very good friends with Sophie Haaser, who is the Registrar of the Museum, and also with Egidio Marzona. Egidio is an important collector and one of the major donors to that Museum. I don’t know how they knew about my Ray Johnson papers, but they did. Maybe we just told them, because I had boxes and boxes full of Ray Johnson correspondence. It began in 1959, and continued until his death [January 13, 1995]. So, what do you do with that stuff? You can burn it. Which would make perfect sense, but you really don’t want to do that either. And it’s not the kind of thing you can leave to children. I mean, what are they going to do with it? The problem was to find a home for the stuff, and MUMOK was interested, so it went to them.

How many letters are in the collection?

There were hundreds. The things we have left—there are a few pieces of correspondence I kept, and the other things we have by Ray are things that he gave or sent to Berty. Very beautiful correspondence. I told you that at the beginning Ray was sending me lobsters, and I was just this dumb kid who didn’t know anything about anything. I didn’t really know how to respond to his messages. Ray put up with that. He was like that. He was a mentor, in a way. But with Berty, it was different. They were two mature artists, and they could communicate with each other through objects. For a while, they were sending each other pictures and drawings of pieces of twisted wire, and sometimes the actual twisted wires, things they found in the streets. They would find these things and send them to each other. There were other things too. Wonderful things. Two or three of the envelopes that Ray sent or gave to Berty are among the most beautiful things I remember him ever to have done.

Well, thank you very much, Henry.

I hope it proves useful in some way.

We’ll see.

I had no idea I could remember all these things.

I really wanted to do this, because as I said at the beginning, I couldn’t find an interview with you in English.

Well, there aren’t any. Nobody bothers with me.