Ashes

Steve McQueen

Thomas Dane Gallery

3 & 11 Duke Street St James’s, London SWIY 6BN, United Kingdom

“I knew Ashes, he was a friend.” That’s the first line of dialogue in Steve McQueen’s film Ashes, shown at the Thomas Dane Gallery in London. The space is hidden inside the stately, bourgeois façades of Duke Street in St. James’s, filled with the airs of establishment, privilege, aristocracy, and tradition. It is rather pleasant to consider McQueen as a commanding presence among this little corner of London: a black filmmaker who opens the wounds of slavery and oppression wide, not just for those feeling the reverberations of suffering through their ancestors, but the wounds of those who propagated it for centuries. Institutionalized slavery began in places like this, in the tiny salons and meeting rooms where men drank brandies and traded stock in human beings as carelessly as they traded stock in tea. Stepping into the two-part gallery space (one is a small walk-up, the other a larger space downstairs where the film is screened) is disorienting as a clean set of rooms without a hint of classical embellishment.

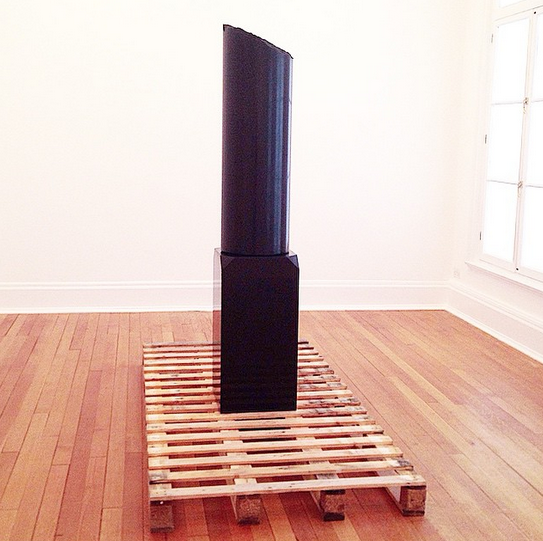

Broken Column, 2014.

The first part of the exhibition centers around a sculpture in the upstairs gallery. First seen is a sketch of a broken black pillar mounted on a white plinth. This curious little drawing wants to be something more, more than a reference to a larger, more prominent structure. But in the next room, the monument stands. A magnificent cylinder of black Zimbabwean marble, cracked at the middle, placed on a wooden shipping crate. The piece is called Broken Column. The title sounds simple enough, but this being Steve McQueen, even the words used to name the work are carefully chosen and expertly handled. The column might have supported some grand home or palace in its place of origin—implicitly referencing an African country—but may not have been strictly limited to Zimbabwe. Now, it stands mutilated and humbled; an artifact ripped from its rightful place and carted off to a foreign environment. It is “broken” (not “cracked” or “halved”), as in a broken man or broken being: one who has suffered and continues to be maligned. It is a “column” (not a “pillar” or “monolith”), once belonging to a greater architectural body and a beautiful piece of craftsmanship, on its own. Its status as an object and metaphor converge at the point of pain, an entity now reduced to little more than something to be bought, sold, and resold many times over. It is, in every sense, enslaved.

Ashes, 2014. Installation view at Thomas Dane Gallery.

The film in the downstairs gallery is screened in a large, dark space with the projection visible from both sides, and visitors are compelled to sit on the floor. On the screen, the shimmering cocoa-toned skin of a black boy with blond-tipped dreadlocks smiles widely for his viewers. He knows he is being filmed and loves every minute of it. He bobs up and down, sitting and standing on the upside-down keel of a small boat cutting through an azure ocean. Overhead, a Caribbean man recounts his memory of a boy called Ashes, who lived in Grenada and had become involved with a local drug gang. Another man’s voice is heard, another acquaintance of the boy, who relays the gruesome details of how he stood up to the drug gang, only to be gunned down in cold blood. It takes several rounds through the dialogue loop for the story to become clear, and for it to become more and more tragic. A boy, full of life and possibility, is just a memory preserved on a grainy filmstrip as he cavorts with his audience through smiles and sensuous swipes of seawater from his face. He represents not only the dark nature of criminal activity and how it seduces those even with ebullient and happy lives, but also with how a film can act as a confessor: a private world where façades can be dropped and desires are visible to the world.

Ashes, 2014. Still. Installation view at Thomas Dane Gallery.

McQueen builds two elements of tribute in two formats. While Broken Column is only a fraction of its former glory, it stands beautifully, nonetheless. Ashes is a memorial with a similar measure of pride; the boy’s end was grisly and anonymous, but he becomes victorious in the guise of his capture on film as a suave, spirited bon vivant. His mastery unchallenged as a visual artist, Steve McQueen has returned to his seat of power in the art world following his triumph with 12 Years A Slave. Long may he reign.