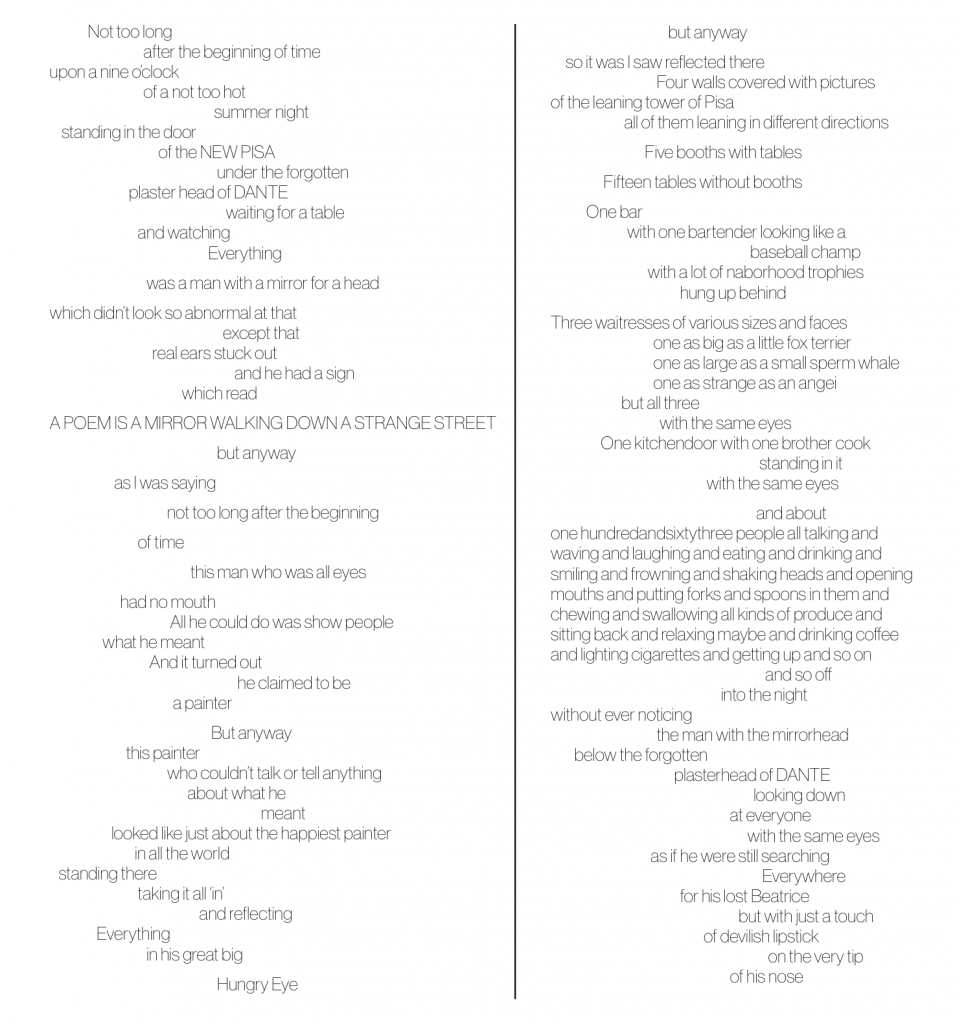

This conversation between Lawrence Ferlinghetti and John Held, Jr. appeared as four installments in issues 15, 16, 17, and 18 of SFAQ, over the course of 2014.

PART 1 OF 4

John Held, Jr.: I’d like to talk to you today about your painting, rather than your poetry or publishing, which receives the bulk of attention directed to you. I don’t know of any painter who had a more difficult childhood than you. I don’t know how deeply you want to discuss this, but I wonder how it impacted your development as a painter?

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: Well, it would take a book to answer that. I’ve got a project going now, which I’ll probably never finish. The book would be called, “Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man,” which would pretty much cover your question. But I don’t know. I don’t think there’s really anything specific that would apply to painting.

After several setbacks in childhood, you found yourself in the midst of a wealthy family, due to your aunt taking a job as a housekeeper.

No. She wasn’t a housekeeper. She was a French tutor for the daughter in that family. In other words, she was the French governess.

At some point she disappeared.

I went back to France with her before she disappeared, when I was only about three or four years old. I stayed long enough to learn the language. When I got to the Sorbonne after the Second World War, I had the accent but had only baby vocabulary. I was in the graduate school and I really had to work my butt off, because everything was in French, including the soutenance. Do you know what that is? The soutenance is to uphold your thesis in public in one of those beautiful Renaissance lecture halls at the Sorbonne, with three professors sitting jury on the stage, and you facing them and the audience behind you. I was more afraid in making a mistake in French than in what I was talking about, because I knew more about American poetry than they did. I could just about say anything I wanted to about it, Walt Whitman, for instance, or Edna St. Vincent Millay. So, actually it happened—my oldest friend in the world, George Whitman, who just died four years ago now—he came to the soutenance. He didn’t have his bookstore yet. He didn’t have Shakespeare and Company. I’m talking about 1948. I think he started Shakespeare and Company in about 1950. It turned out those academics—this is before the 1960s revolution when the students revolted against the antiquated system and the antiquated teaching methods—everything was so boring for those professors—here comes this guy from America who’s spouting off about poetry they’d never heard of, and it got quite lively. I got through the soutenance.

There’s a great story about this, which I wish you would relate. You were doing quite well during the thesis defense and then a lull occurred and the tide seemed to shift, and you gave them a great quote about translation.

Where did you read this?

It was in the Neeli Cherkovski biography [Doubleday & Company, 1979].

Today I’d be murdered by women’s lib. I was just quoting a famous French author, someone like Balzac, who said, “A translation is like a woman. When she is beautiful, she is not faithful. When she is faithful, she is not beautiful.”

It’s a great quote, and quite perceptive about the art of translation.

Well, I’d rather not noise that quote around these days. I’d be murdered by my fellow editors at City Lights.

Well, it helped break the ice for you during your thesis presentation.

It got a big laugh from the three professors, because they weren’t used to any levity or wit.

George Whitman was the most important American bookseller in Europe, so it’s very interesting that your lives were so intertwined.

Have you been there to Shakespeare and Company?

I was there in 1978, and had the pleasure of being taken up to his apartment over the shop, which I considered a great honor.

I was going to graduate school at Columbia in 1946, and his sister was in the graduate Philosophy Department. I met her there and when I went to Paris, she gave me George’s address.

He was one of the first people you met in Paris.

The first. His was the only address I had, and he was living in a third-class hotel, the Hotel de Suez on the boulevard Saint-Michel. Really a dump. He had a room about ten feet by ten feet, and it was stacked up to the ceiling with books on three walls, and George was in the middle in an old broken down easy chair making his dinner over a can of sterno. Sterno was a can of fluid you would buy and light it with a match. It was what bums used . . .

They used to drink it. It had alcohol in it.

George was selling books out of his hotel room. So, that was the idea when I got to San Francisco—I thought of having a used bookstore like George’s. But unfortunately, just then, in 1953, what became known as the paperback revolution, just took over the book industry. Up until then, there were no quality paperbacks, just cheap thrillers, some science fiction and murder mysteries. The big publishers in New York started publishing quality fiction in paperback, and there was no place to buy these books, because they were only merchandise on newsstands. So, that’s where City Lights rushed in. We were the first ones . . . We’re on the wrong subject now. We’re supposed to be on art.

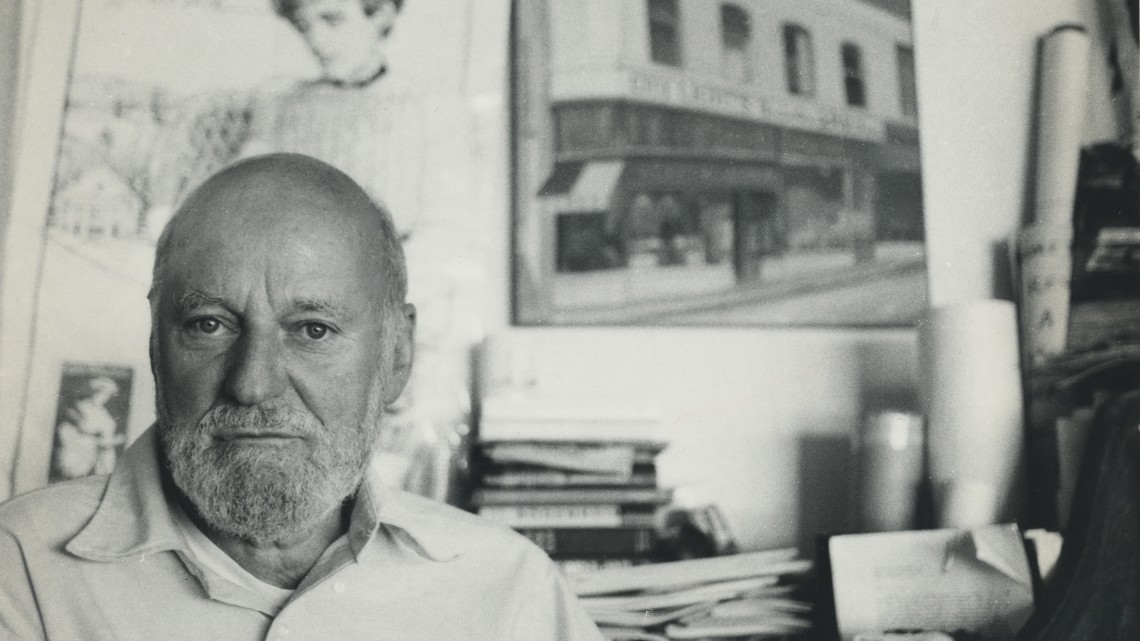

Lawrence Ferlinghetti in front of his San Francisco bookstore City Lights in 1996, as seen in Ferlinghetti: A Rebirth of Wonder, a film by Chris Felver. A First Run Features release. Photograph by Chris Felver.

It’s good background. You met Peter Martin, and you stumbled into this when you saw him opening up a bookstore.

You know who he was?

He edited Beatitude, didn’t he?

No. No. Beatitude came along long after he left. He had a little magazine called City Lights, which was the first pop culture magazine that I ever saw. He published the first Pauline Kael film criticism. He graduated from Berkeley about 1950, maybe. Pauline Kael was one of his contemporaries, and she went on KPFA, and then she became famous at the New Yorker. The main thing about Peter was he only stuck around for a year. He got divorced and moved to New York. He was the son of Carlo Tresca. You know who that was?

He was a Communist that was assassinated, right?

He was an anarchist. Assassinated on the streets of New York. Probably by the mafia. We had this anarchist background for the bookstore. I was getting my anarchism from Kenneth Rexroth on his weekly programs at KPFA.

Can I just go back to New York City before we get to San Francisco? You did your Master’s thesis at Columbia University. It was on the critic John Ruskin commenting on the work of the painter J. M. W. Turner.

It was Ruskin on Turner. Ruskin wrote a series of volumes called Modern Painters, and it was all pointed toward Turner. The whole thesis of the series was that there was no light in the paintings until he got to Turner, and then suddenly light burst on the canvas. I was in the Columbia Library and found the Kelmscott Editions of Modern Painters by Ruskin. Quarto size, beautiful books printed by the Kelmscott Press around the 1890s in England. Full reproductions of all of Turner’s works.

He was almost an Abstract Expressionist in certain works.

The last show I saw of Turner’s works at the Tate Gallery, almost twenty years ago, was totally – no figuration left. The whole room, a huge room, was nothing but pure light – just canvases with light and no figuration in the paintings, or hardly any. Extraordinary.

The interesting thing is that you were writing about a writer and a painter, and later on, you would replicate that in your own life. Although the thesis we were talking about at the Sorbonne was specifically about poetry and the city, and didn’t have anything to do with painting. But while you were in Paris, in addition to attending the Sorbonne, you were attending the Académie Julian.

Well, I was in and out of there. I wasn’t registered in the school. I was just going to their open studio. For about two francs, you could draw from the model. It was great. Well, we did get to the art.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but when you did move to San Francisco, you lived in the old studio of Hassel Smith [the painter then teaching at the California School of Fine Arts]?

Oh, you couldn’t live there. He had just moved out. He was just rejecting figurative painting and becoming a totally abstract—non-objective—painter. I make a distinction between abstract and non-objective. Abstract is still an abstraction of an actual physical object, whereas non-objective doesn’t begin with an abstraction. New York Abstract Expressionism is actually a misnomer, because they were doing non-objective painting. It was one of their principle grounds that they weren’t basing it on anything that existed, but it was a totally new, novel creation every painting.

You were doing art criticism for Art Digest around this time.

Hubert Crehan was a painter living in Berkeley, and he was the West Coast editor of Art Digest. He got me to do a monthly column, and it happened that the Anton Refregier murals were in the post office—the Rincon Annex at the foot of Mission Street, about one block from the Embarcadero—and they’re still there. Because what happened was that the American Legion or some other organization wanted to get rid of them, said they were not obscene but defamed American history. Actually, the murals depicted white men beating up Indians and killing them and so forth. I wrote a column defending the murals, and eventually they weren’t taken down, so they’re still there. Refregier was evidently a Communist, and that was a strike against him, and they wanted to get rid of him and his murals.

What other things did you write about for Arts Digest?

I also did a review of Jay DeFeo. I was brand new in town. I didn’t know anybody in the art world. So, I could say anything I wanted to without offending my friends, because I didn’t have any friends in the art world. I wrote that looking at one of her paintings, I didn’t know whether she painted it or backed into it. And she never forgave me for that. Twenty-five years latter I met her at some party, and she really brought it up. [Laughs]

That was a good way to meet artists and get to know the art scene in San Francisco – for better or worse.

It’s too bad Kenneth Baker [San Francisco Chronicle art critic] can’t commit himself more. In particular, he wouldn’t make a statement like that. In fact, we’re wondering at Krevsky Gallery, where is Kenneth Baker? He’s never reviewed a show at the Krevsky’s gallery, and he’s been there for twenty years. There was a very important show curated by Peter Selz at the Meridian Gallery about a year ago. It was really an important show, and Baker didn’t review it.

I reviewed it. That was an incredible show. It had yourself, Jack Hirschman . . . I believe the name of the show was “The Painted Word,” if I remember correctly. Robert Duncan was in the show. The person who really impressed me, aside from yourself, was Kenneth Patchen. Patchen’s work was really unbelievable. Did you attend salons with Patchen?

He didn’t go to parties or salons. We published two of his books of poetry, and we had a publication party at City Lights, but he never showed up. He was only living three blocks away.

Did you ever attend the salons hosted by Duncan and Jess, by the way?

No. I went to Kenneth Rexroth’s Friday night soirees, and Duncan was often there. Generally, I stay away from discussion groups of any kind. At Rexroth’s you just went and listened. He had encyclopedic knowledge. When I first went there, I had just arrived in town, and I was totally awed by his range of knowledge. Later, I realized how much of it was . . . he had a way of letting you know that he knew all about whatever the subject was. [Laughs] Many times he made up things and exaggerated things, but there was a huge amount of knowledge there. It was extraordinary what he could come up with.

But he would say things like, “Oh yeah, I met Oscar Wilde when he came through San Francisco.” Well, you look up the facts and you find out that Wilde was here around 1910 or 12, and Rexroth would have been two years old near Chicago. [Laughs] He had an autobiography published by Doubleday, and Doubleday insisted it be called an autobiographical novel. There were so many doubtful truths in there. But, he was an old Wobblie and you could get great anarchist arguing points from him. He could make you believe that anarchism was a possible way to run society. Which was quite possible back when he was still alive in 1960, but today the population of America has doubled since that time, and so what was possible with a small population, like the 19th century, is (now) impossible to manage that many people on anarchist principles.

Anarchism was one of your first “coming of age” educations, wasn’t it? Previous to that you had been an Eagle Scout. And when you were still in the Navy, you witnessed the effects of the bombing of Nagasaki only weeks afterwards. That also had a profound effect on your thinking.

Well, I didn’t know it at the time, but years later I started saying that seeing the devastation in Nagasaki about six weeks after the bomb was dropped made me an instant pacifist. That was kind of an exaggeration, because I don’t remember consciously thinking anything like that at the time. I was still a good all-American boy. So, it was only after I came out here under the influence of Rexroth and started thinking things like if the Japanese were white skinned, we would have never dropped the bomb.

PART 2 OF 4

I’d like to return back to your Paris days, if I might. That was a heyday for Surrealism. Duchamp was there, André Breton, and they were involved with staging a Surrealistic exhibition about that time.

That was the dominant trend in Paris at the time. I knew the son of the biographer of Marcel Duchamp, Robert Lebel. His son Jean-Jacques Lebel, organized a series of international poetry readings starting in the sixties, and I went to several of them. It was called The Festival of Free Expression. They were really some events.

Did you ever meet Duchamp?

No. That was an older generation. Those guys, Duchamp and the Surrealists, were in the twenties.

But Duchamp was in New York in the fifties and sixties.

Yes. They all came over to New York, and that’s why Jean-Jacques spoke English fluently with a Brooklyn accent, because he was a little kid in Brooklyn when the Surrealists were escaping the Nazis. He’s still very active in Paris. He paints and does assemblages in the Surrealistic tradition.

You still have connections to Paris, and go over occasionally?

I haven’t been since George Whitman died. I used to try and go practically every year. For many, many years Shakespeare and Company was always the center for the literary expatriates. Black poets like Jake Jonas were always there. It was where you went to pick up your mail—this was before there was an Internet, or anything like that. Are you going to rewrite the answers or are you going to print them verbatim?

I’m going to transcribe them verbatim and then you can look them over and edit them.

I don’t even want to see it. I just wondered which way you’re going to go, whether it’s going to be verbatim, or if you’re going to rephrase everything.

Verbatim. Your words are eloquent and don’t need elaboration. Let’s talk about the fifties for a while. You were just starting City Lights and publishing your first works. I think it’s descriptive that your first book was called, “Pictures of the Gone World” [City Lights, 1955].

Yeah, but let’s stick to the painting subject. In the 1950s, I got Hassel Smith’s painting studio at 9 Mission Street. It’s the Audiffred Building. It’s at the foot of Market Street and the Embarcadero, and there was no electricity over the ground floor. On the ground floor was the Bank of America. On the second floor we shared the floor with the Alcoholics Anonymous club. On the same floor was Frank Lobdell—his studio was there and in the back of the floor was Marty Snipper, who was an art teacher. There was no heat over the first floor and no electricity. I had a small pot bellied stove for heat. So, it was just like a Paris studio. It was really studio size, like in Paris. In North Beach today, there are no studios. People have one room, and they call it a studio. [Laughs]

You were close to the Art Institute, then the California School of Fine Arts . . .

I went there for many, many years, drawing in the open studio from the model.

This was in the fifties?

Fifties, sixties, seventies, and I got my studio at Hunters Point Shipyard in 1980. So, I’ve been at Hunters Point for thirty-three years. I have a huge studio there. It’s sixteen hundred square feet. I was one of the first ones who got there, and I picked out one of the best spaces. We have a model there once a month for three hours. About twelve people come. A lot of the drawings that are now at my show at Krevsky’s were from model sessions. You’ll see that most of the work in there is quite recent, from the last couple of years, except for three or four oil paintings that are older. Two are very recent. There’s a painting in the show from the fifties. I sold it to a woman about 1960, 1963 maybe, for a few hundred dollars. I always wanted to get that painting back. I wish I’d never sold it. I had no way of getting in touch with her. I didn’t know where she was. Just six months ago, her ex-boyfriend called me. And they hated each other now, evidently. But, he had the painting. He was in desperate straights, because he had some fatal disease and he had to have an operation immediately, and needed thousands of dollars. So, he was desperate to sell this painting, and so I bought it from him. I was very happy to get it back. It’s surprising. The date on the back is 1956, so I did it probably at 9 Mission Street. I might have done it at 706 Wisconsin Street on Potrero Hill, where I moved about that time. What’s so striking is, that it’s the same way I paint today. It’s like I haven’t progressed a bit. In fact, it’s the best painting in the show, which shows I’ve gone backwards. [Laughs]

Lawrence Ferlinghetti in front of City Lights, then featuring a host of banned books. Courtesy of the Internet.

What I find interesting about it—it’s a figure with arms upraised—very reminiscent of the City Lights logo.

No, it has nothing to do with that. I didn’t adopt the City Lights logo till the late seventies. The City Lights logo was taken from the Koch “Book of Signs,” published by Dover Books. And these are medieval house marks. So, the City Lights logo is a medieval house mark without any specific meaning. That was long after the image I painted in the 1956 painting. It’s a coincidence they happen to be similar.

And the name City Lights, was that was Peter Martin’s doing?

That was the name of his magazine. We got permission from the Chaplin Estate to use it as the name of the bookstore. We got a telegram from the Chaplin Estate and I’ve been tracing down that telegram ever since. I know where it disappeared, but the trail sort of ended, and I’ve never gotten a copy of it. It was an old Western Union telegram.

It’s not at the City Lights bookstore archive at the Bancroft?

No. It isn’t.

You were fond of Chaplin.

Just as everyone else was. Except the House Un-American Activities Committee.

You’ve had a lot of success with your painting in Italy recently.

The first big painting show I had in Italy was in 1996 at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome. The catalog for it is bilingual. The photography is not nearly as good as the recent catalog I gave you (Lawrence Ferlinghetti,“60 Years of Painting,” Museo do Roma in Trastevere, Rome, Italy, 2010). This is a very small painting [referring to a reproduction in the catalog]. It’s almost full size. It’s owned by Rita Bottoms, who used to be the Curator of Special Collections at UC Santa Cruz, and I gave it to her many years ago. It’s called, “Portrait of Rosa.” That was a big show. The Museum looks like the Metropolitan in New York with a huge facade with banners in front when I was there—“Ferlinghetti.” It was really a sensation to see them.

Your archivist Diane Roby told me that whenever you go to Italy, the television crews follow you around in the streets.

Well, I get full pages in all the dailies there. I have a show up in Naples right now, and there are full pages in La Repubblica. In this country—nothing.

Kenneth Baker [San Francisco Chronicle art critic] still isn’t writing about you.

[Laughs] Too bad he can’t read Italian.

A backer of yours in Italy was Francisco Conz, who passed away a couple of years ago and was associated with the Fluxus artists.

That’s right. He really promoted the Fluxus movement in the 1970s and 80s, but when I came along, when I first met him in the 1990s, he adopted me as a Fluxisti and gave me a couple of shows in Verona. One in Verona. One in Florence. He drank too much and fell off a railroad station platform. He was in a wheelchair the last few years of his life.

Did you know any of the other Fluxus artists, like Dick Higgins, who ran Something Else Press?

I knew about Dick Higgins, although I never met him. They were like an earlier generation of Fluxus artists.

They started in the early ‘60s with George Macunias.

I knew all the names, but I never met any of them. I didn’t see them as very radical.

No?

Not from a political point of view, or as visual artists. They were original but not radical.

Who are some of the contemporary artists that you do appreciate?

Oh well, in Italy Francesco Clemente is one of my favorites. There is a group called the Trans-Avantgarde.

There was a famous Italian critic who was the champion of the group.

He has a main essay in my catalog.

He called you the Father of the Italian Trans-Avantgarde.

That’s right—the Godfather.

He’s an important critic. I think he was the organizer of the Venice Biennale for many years. Susan Landauer has written about you as well.

Yes. She wrote the introduction to my last George Krevsky show.

I believe she and her husband Carl had an essay about you for your 2010 Italian exhibition in Rome [Paint the Sunlight and All the Dark Corners too: The Art of Lawrence Ferlinghetti]. Did you ever go to shows at The Six Gallery?

The Six Gallery was associated with the painters of the American Beats. Bob Levine was a painter . . .

They were basically students at the California School of Fine Arts, Wally Hedrick, Deborah Remington, De Feo . . .

Michael McClure was friends with many of them.

The Last Gathering of the Beats. City Lights Books, 1965. Front Row (Left to right): LaVigne, Murao, Fagin, Meyezove (lying down), Welch, Orlovsky, Homer. Second Row: Meltzer, McClure, Ginsberg, Langton, Steve, Brautigan, Goodrow, Frost. Back Row: Levy, Ferlinghetti. Courtesy of the Internet.

Did you know Wallace Berman?

I knew him, I mean I met him. He was a good friend of McClure. But the Six Gallery was associated with the Beats, not with the painters in the Bay Area Figurative group like Diebenkorn, Elmer Bischoff and David Parks. There was quite a divide there. The San Francisco figurative painters were alkies. They drank and had great parties and jam sessions and drank. Whereas, down the street, twelve blocks away, were the Beats smoking dope and not drinking alcohol, mostly, except someone like [Gregory] Corso did both. But, there was no communication between these two groups. I mean, there was a revolution in poetry going on in one end of North Beach, and a revolution in painting going on at the other end near the Art Institute, and there was no communication between the two. It’s like dopers and alkies, and The Six Gallery is more or less associated with the Beats, like Bruce Conner, who came slightly later. His basic vision, like the famous pieces he has at the San Francisco Museum of [Modern] Art are very definitely LSD visions. Like cobwebs and everything—definitely a dope vision, not from drinking alcohol.

They had their own galleries like Batman Gallery.

There was a generation gap, too. The figurative painters were mostly veterans of the Second World War and the Ginsburg and Kerouac generation was ten years behind that. When I was in Paris, some of those painters were there too, but I never saw any of them.

What about Sam Francis and Claire Falkenstein, who were there about that time?

I didn’t know her. They didn’t make any contact with French culture as far as I could tell. There was a seminar at the Legion of Honor about fifteen years ago where they had all the painters there who had been in Paris. I don’t know what they were doing there. They didn’t seem to know anything about what was happening in the Paris art scene.

PART 3 OF 4

One thing that I appreciate about your history is that you’ve never gone after grants of any kind, either for yourself or City Lights.

For City Lights and myself, we’ve never applied for a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, because from the Leftist point of view, it’s rather hypocritical to attack the government’s policies, and on the other hand, take money from them in the form of grants. No matter how you deny it, you’re still indebted to them in some way once you take money from them—whoever gave it to you. As far as the publishing part at City Lights, the publishing part of City Lights wouldn’t want to be associated with taking grants from the government, because publishers, like any other member of the press—the New York Times wouldn’t take grants from the government, because it would compromise their objectivity, if they had any to begin with. [Laughs] In the same way, it would be compromising for City Lights to take government grants, and also I’ve never applied for—oh, I did apply for a Guggenheim before I had City Lights bookstore? I think I was still at Columbia, and I had a poetry teacher named Babbitt Deutsch. I remember her saying things like, “How can we write the Great Russian Novel in America while things go on so unterribly?” I did send her a manuscript, and I asked her to recommend me for a Guggenheim, but she turned me down. [Laughs] As an undergraduate, I went to Journalism School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and my favorite professor there was a man named Phillips Russell, in what they call a creative writing class. And years later I sent him a copy of Coney Island of the Mind, and he wrote back a postcard that said, “You are coming up in style and form.” [Laughs]

It’s always good to get positive feedback from an old professor.

Right. We should get back to the art.

I wanted to mention that although you haven’t received grants in your lifetime, you have been admitted to prestigious academies—The National Academy of Arts and Letters.

The Academy of Arts and Letters. It must be the most prestigious academy in America. It’s different than the Academy of American Poets, for instance. This is called the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and it’s got every important novelist and poet—really an extraordinary roster. You can’t get in until someone dies. There are only so many places.

There are painters in it as well, I believe.

Of course.

Because I believe Bob Bechtle is in it. You know Bob?

Yeah. Painters and sculptors and writers of all kinds.

And then you’re in Italian . . .

Well, I used to be associated with the American Academy in Rome, but there isn’t any financial connection anymore. I’ve stayed at the American Academy in Rome, which is a beautiful villa on top of one of the seven hills. I don’t like to stay there, because no one there speaks Italian. You might as well be in graduate school in America.

When were you at the American Academy in Rome?

I was in and out of there a couple of times. I’ve never stayed there. When I go to Italy, I like to speak the language. That’s one reason I go there. I retrieve my father’s language.

He was from Brescia.

Brescia is near Verona, just southwest a couple of hours. It’s a commercial town. Francesco Conz staged a number of events there. I’ve been there several times. There are still some Ferlinghettis living there in the outskirts of the town called Chiari, some miles from Brescia. There is a big Ferlinghetti family there. A Ferlinghetti house, and they gave me the keys to the city. Francesco Conz was a great publicist and he arranged the whole thing. We drove up in a big limousine, and we got out in front of the little City Hall. The mayor and all his henchman were lined up with sashes across their chest, the band started playing—a high school band. There’s a special name for those bands. They wear medieval costumes. So, we stepped out of the limousine, and the mayor embraced us with a kiss on both cheeks, everybody waved their arms around and shook everybody’s hand in sight, and then we went into the City Hall and everybody made a lot of florid speeches, and I made a speech in bad Italian, and then I met this whole family—the Ferlinghetti family—three generations. That was about ten years ago. Since then, Francesco Conz helped me trace down my father’s birthplace in the city of Brescia. We went there, and Conz was really a smart publicist. He sent a cameraman with me, because he figured he’d get some publicity out of it. So, we went into this really poor section of town, really old section, and we found the address, but here was no longer a single house there, it was now a four-story apartment building—pretty beat up looking building. We rang a bell, and then another bell, and nobody came. Finally, a guy comes out of the basement, looked like he must have been the superintendent, and he’s yelling at us to get the hell out of there. So, we started walking back to the car, and a big police van sirened up and put us up against the wall and asked for our IDs. The cameraman got the whole thing on camera, and he immediately sent it—you can do that these days—to all the newspapers. The next day, all the big papers—La Repubblica, Il Manifesto—had this big story: “Poet in Search of His Father Arrested.” [Laughs] But I wasn’t really arrested. I was stopped. I told Francesco Conz, “Why did you say I was arrested? I wasn’t really arrested.” He said, “Well, the mayor of the town owes me a favor now, because I told the press that the mayor got you out.” [Laughs] That’s the way they do things in Italy. That was only five years ago.

No. 5 from Pictures of the Gone World: Pocket Poets Series Number 1, by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, published by City Lights.

Do you have any other shows lined up in Italy?

Well, I have a show in Naples right now. This is the third stop for this show. It’s a show based on Ulysses. I did a lot of drawings when I was visiting Giada Diano, who lives in Reggio Calabria. That’s down at the foot of Italy—the toe of Italy, just facing Sicily. Ulysses passed by the foot of Italy. He went between Italy and Sicily in the Straits of Messina. That’s where the famous chapter in the Odyssey is, where he escapes the monsters Scylla and Charybdis. He escapes the monsters and eventually goes back home where Penelope was still waiting for him beating off the suitors. I added a chapter to the Odyssey. I drew all these works on paper of Ulysses escaping the monsters in the Straits of Messina, but then he went ashore to Reggio Calabria, which was then a little town, and he shacked up with a sexy milkmaid and produced a lot of children, which is now quite evident in the profiles of the present inhabitants of Reggio Calabria. They have very Greek profiles, just as in Sicily there is a big Greek influence. I made the drawings to go along with this, and that’s what’s in the show in Naples right now.

Do you have any plans to bring the show to this country?

I don’t know. Giada Diano is setting up the Lawrence Ferlinghetti Cultural Center, and if she succeeds, I intend to give the paintings to that Center.

And that’s in Italy?

Yeah.

Here in this country, you have a painting archive at the University of Santa Cruz.

Well, yeah. They don’t have many paintings on canvas. They have one big painting on canvas, which I painted in an old hotel, on what is now the mall. It’s now condemned, but when I was there in the 1989 earthquake I did a painting, quite large, about seven feet, in this great big old hotel with high ceilings and large French windows. I gave that painting to UC Santa Cruz, because Rita Bottoms, the curator there, had done so much to promote my art. Besides that painting, they have about one hundred works on paper—drawings from way back then—from the eighties, I guess.

Do they just have art from you, or do they have other Ferlinghetti ephemera?

No. I have to stick with the Bancroft Library [UC Berkeley] for the literary works.

Right. And they have your correspondence at the Bancroft?

Oh yeah. It’s very extensive.

And they have the City Lights Archive at the Bancroft, as well.

It’s a separate archive. It’s enormous. There’s an interesting story about James Hart, the former director there, who I mentioned to you was a member of the Bohemian Club [San Francisco]. When he wanted money, all he had to do was call up one of the members of the Bohemian Club. But specifically, in my case, at City Lights we were changing the name of twelve streets to literary names. This was about 1989. There was a street just behind where the present Transamerica Building is now, which is where Mark Twain was reputed to have worked in a bar, and so we picked out this alley that we were going to call Mark Twain Alley, or Mark Twain Court. We got a letter from the Transamerica real estate department saying, “You can’t have it, because we have plans for this alley. Thank you very much. Goodbye.” So, I called up James Hart at the Bancroft Library, and I told him the story, and he said, “Oh, that’s old Richard! I’ll just call up Richard and put a bug in his ear.” He’s talking about the President of Transamerica. [Laughs] So, a week latter, I get a letter from the President’s office saying, “Oh, we’re so sorry, that dim-witted real estate department didn’t know what it was talking about. Of course, you can have that alleyway.” [Laughs] So now it exists, right behind the Transamerica building. It’s called Mark Twain Court, I think. It’s only half a block long.

We talked before about your painting show at the Meridian Gallery, which was curated by Peter Selz. Peter Selz and you were born three days apart.

Yeah, I’m three days older than he is.

That’s pretty amazing.

He was born in Vienna, I believe.

In Berlin, I thought. [We were both wrong. Selz was born in Munich.]

He came here to escape the war. I knew that. Well, you know he’s an important person in the art world. You would have thought that show would have received some notice.

That was a show worthy of being traveled.

But there’s no art critics here any more, except now that SFAQ has sprung up.

It’s been pretty dry. There really hasn’t been a good art magazine in San Francisco, aside from Artforum in the early sixties.

I know. The art magazines have to be supported by the galleries, and the galleries here aren’t big time. They’d liked to be big time, but they don’t have the money. They don’t deal in money that big, the way the New York dealers do. In a way that’s a blessing. Because in New York, it’s a system that’s so much based on money. For instance, a gallery will take out a full page in ARTnews, and then the ARTnews critic has to go and review the show. Now, he’s free to put the show down, or damn it, or anything he wants. But still, there’s a review of the show in ARTnews. It’s directly related to the fact that the gallery took out a full-page ad. So, the critic has to do his best to make the gallery look good. It just goes around and around in a circle like that.

It’s a vicious circle. Have you ever given any consideration to writing art criticism, as you once did?

I don’t have time anymore. I was doing that because I didn’t have a job. It takes a lot of work even to write a short review. I don’t know. It didn’t take me a lot of time to write that sentence about Jay DeFeo. [Laughs]

Its’ nice to see she’s achieved a certain amount of recognition lately. You’ve been in some great group shows lately the last few years, associated with the Beats—a name you don’t care for especially—the Beat Culture show that came out of the Whitney. I think you were included in that.

Yeah, but that’s the trouble. As a painter I have a hard time being recognized as a painter, and not just a poet who also paints. It’s really a drag to get that all the time, because I was painting before I ever had any poetry published at all, or anything published, as far as writing goes. I was painting in Paris when I wasn’t writing. I was just too busy to promote myself as a painter. I didn’t hang out with any of those San Francisco painters. They didn’t know me, and I didn’t know them. The only one of the figurative group that seemed at all interested in the poets was James Weeks. I used to have coffee with him once in a while in North Beach. But otherwise . . . Well, now I know Charles Campbell quite well. He had a wonderful gallery that was historically important near the Art Institute. He’s going strong. I saw him the other day. He was at the opening of my George Krevsky show. I think he’s ninety-eight. He was the power behind the figurative painters.

PART 4 OF 4

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: The Museum of Modern Art is closing for two years. I wish I had seen The Clock [Christian Marclay]. Did you see The Clock?

John Held, Jr.: I saw about forty-five minutes of it.

I wanted to, but . . . SFMOMA has this gallery at Fort Mason, which is for local artists. But that’s how they get out of having anything to do with local artists at SFMOMA itself. I met one of the directors of the museum at some party, and he told me, “There are no great painters here. If there were, we would be paying attention.” I mean, can you imagine the director telling me that?

Yes, I can . . . unfortunately.

Well, it may be true. I shouldn’t say that. There are not many of the old style painters who really flung paint the way it was in the days of the 1950s or ‘60s with the abstract expressionists, where you just ran in and threw paint at the canvas. I did a lot of that. There are very few old style oil painters. At Hunters Point now, there are all kinds of other mediums.

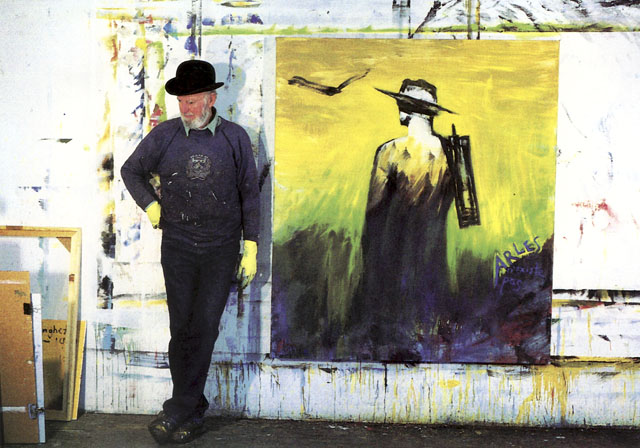

Ferlinghetti in his studio, working on his van Gogh series. San Francisco, 1994. Courtesy of the Internet.

Do you use oil or acrylic?

I use oil and acrylic. I use oil on acrylic. Do you know about that?

No, but it’s an interesting combination. Tell me about it.

This is basic. I don’t know how many have learned it in art school. People ask me, “What formal training did you get at an art school?” Well, I got the formal training myself. For instance, there’s a wonderful book called, The Natural Way to Draw, by [Kimon] Nicolaides, who was an art teacher at the Art Students League in New York for many years. I went through that book page by page. And then I learned lithography on stone in a four hundred year old litho studio in Paris called Stampa Bulla. I worked in a lithography studio in Prague, and just last year I worked at the Kala Institute in Berkeley. At the Krevsky show there was one of the portfolios. Lithography on stone—the way it used to be done over several centuries. Oh yeah, acrylic and oil . . . If you put acrylic on the canvas first, because with the change in temperature and humidity, the acrylic doesn’t expand and retract. Whereas, oil will expand and retract. So, if you put acrylic on top of oil, the painting is going to expand and retract and crack the acrylic on top of it. So, the rule is you put the acrylic down first and then you can put oil on acrylic and it won’t crack.

Is this a standard technique of yours?

It’s not me. It’s been professional knowledge since acrylic existed. It makes a big difference.

Painters use acrylic because it dries faster.

Yeah, but then they don’t use oil also. I put oil on acrylic.

Which is unusual, I think.

You do the underpainting in acrylic. Acrylic has gotten very good. It’s gotten to the point where it’s sometimes hard to recognize it’s not oil painting. But still, there’s a difference. One you get the underpainting on, it goes much faster.

I should mention some of your paintings include text, which I think is effective. Kenneth Patchen did something quite similar.

Here we go again, attaching me to the literary world. It’s a separate activity, as far as I’m concerned.

I like crossover—the combination of worlds. What do you think of Patchen’s work, for instance?

Well, as far as pure art goes, it’s really cheating to put words on the canvas.

A point well taken.

But nevertheless, I often can’t resist, especially if I’ve got some famous poetic line buzzing around in my head from decades before. Like I did a portrait of Ezra Pound, and I took one of his most famous lines and painted it on the canvas. The line was, “I have beaten out my exile.” I couldn’t resist putting it on there.

You often have images that reoccur. Birds, for instance.

Last night the Giants played the San Diego Padres, and they lost in the thirteenth inning around midnight. By then the birds were circling around the field. This morning, I asked Jack Hirschman, “A hitter hits a fly, and the ball hits a bird. What would be the ruling on that?” You know?

[Laughs] No.

Fowl ball.

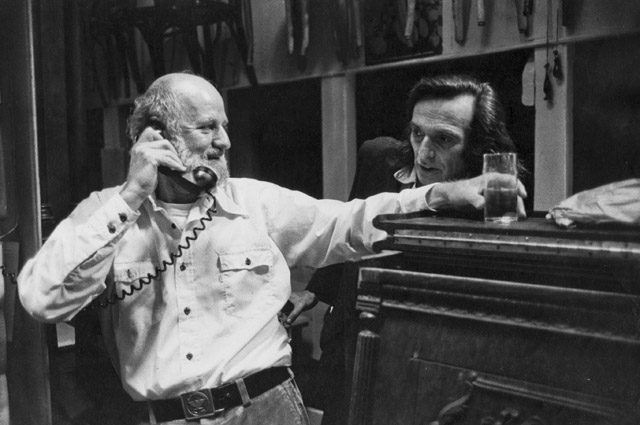

Ferlinghetti & Jack Hirschman. Courtesy of the Internet.

It would be a foul ball? You came up with that, or Hirschman?

I did.

Oh, fowl ball, F-O-W-L.

That’s right.

[Laughs] I’m a bit slow. Are you a baseball fan? I know Jack loves the Detroit Tigers.

I sure am.

Another recurring motive is water.

I love being on the sea having been in the Navy for four and one half years. I never had a desk job. I went from one ship to the next. I just loved being on the sea. Luckily, I was on wooden ships the whole time. Wooden subchasers, 110 feet long. I worked on fishing boots in New England, and I knew how to handle small craft—piloting before the war. Instead of being on some big battleship, I got to be my own boss, and a skipper of a subchaser. Really close to the water. Ten feet above the water. Whereas, if you’re on an aircraft carrier, you’re a hundred feet in the air, and it’s not the same thing.

It’s pretty impressive you were doing something like that in your twenties.

I know it.

Ferlinghetti, Captain of Sub-Chaser 1308 during World War 2. Invasion of Normandy, 1945. Courtesy of the Internet.

We should mention that you were involved in the invasion of Normandy, as well. That had to have had some effect on you.

[paging through a book] Achille Bonito Oliva—just so you’ll have it.

He’s the Italian critic who called you the grandfather of the transavant-garde.

That’s right. Sorry I can’t give you this one. The other one has beautiful photography.

A lot of art books are printed in Italy these days.

That’s not new. It’s been going on for a long time. The printing is just so much better—and cheaper. Even with the euro—well it was much cheaper before when the euro was more in our favor. After the Second World War, we were the conquerors. We set the exchange rates. That’s why it was so cheap for students like me on the G. I. Bill in France. I think we got $60 a month besides the tuition being paid. We got that much to live on, and I had about three times as much money as any French student I knew.

Well, as you mentioned, there were a lot of Americans over there. One person who attended the Académie Julian about the same time as you was Robert Rauschenberg.

I wish I’d known him.

I looked it up. 1947, 1948.

Yeah, we probably passed each other in the hall. As I said, I didn’t take any formal classes. It was so cheap. The model was like twenty francs for three hours, or something like that.

You’ve always drawn from the model.

Oh, yeah. Which is totally out of fashion. I mean, easel drawing is totally out of fashion. Drawing from the model is considered old hat. A friend of mine, who is a professional lithographer, came over for one term to teach at a San Francisco art school. He saw that the students were casting photographs onto the stone. He said, “Why are you doing that?” They said, “Well, we don’t know how to draw.” [Laughs] So he packed up and went back to Italy. “You don’t need me here.” These days, one thinks of themselves a painter or poet just by saying so. That’s it.

Or what’s worse—an artist.

Any words on paper you can call a poem. And any paint on anything can be a painting. So where do you go from here?

Wayne Thiebaud calls himself a painter, not an artist. One shouldn’t refer to oneself as an artist. That’s best said by another. But at 94, I think you could probably get away with it. After all, you are in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Have you ever gone to any of their meetings?

I went to the first meeting when I was installed, but I haven’t been back since, because New York is great when you’re young, but the older you get the harder it is to navigate New York. It’s a major accomplishment to get across town these days. If I had a lot of time, if I had nothing else to do, if I didn’t have a bookstore, I’d go to live in the Village again, where I lived when I was going to Columbia. But the Village isn’t even recognizable anymore.

There’s no there there anymore.

When Gertrude Stein said, “There’s no there there,” she wasn’t talking about Oakland— everyone thinks she was talking about Oakland. She was talking about the middle western city where she came from, Pittsburgh—but it wasn’t named Pittsburgh when she was born, it was named something else.

Did you see the Stein shows at SFMOMA and the Contemporary Jewish Museum?

The Jewish Museum received quite a bit of criticism for having the Stein show, because [Gertrude Stein] was protected by the Nazis and was never touched. There was a story in the New Yorker, which laid this out some ten years ago. In fact, she made some rather raw comments when she found out the Jews were being exported to the death camps. So, there is good reason for the Jewish Museum to be criticized for showing her work.

They have the Allen Ginsberg photography exhibition there now.

Allen had a marvelous eye. Just terrific. But he also had a terrific publicity eye. As soon as he saw two people who were friends of his, he immediately sensed the future publicity. Getting a picture of Gregory Corso giving a statue a kiss in Washington Square, or something like that. So, he has all these marvelous photographs, a lot of them just personal shots that he took. He was lucky, because he had Robert Frank to produce the final prints. Anyone can go around with a box camera and take pictures, but it’s who makes the final print that makes a huge difference. I don’t know how many of his photographs were printed by Robert Frank, but Robert Frank had a lot to do with it. He was good. Allen was an omnivorous artist. He was an artist. He wasn’t just a poet. He was an extraordinary person. He had an omnivorous mind. You could see him at some party. He’s talking to someone who nobody knows, some kid who just wandered off the street, and Allen is talking to him for half an hour. And everyone is wondering, “Who’s he? Why’s he talking to him?” And Allen is just siphoning up the kid’s brain. He’s very interested in what the kid is saying. It’s really remarkable. When we went to Australia, we stopped in Fiji and went around the island on a bus, and we were walking on the dirt street of some town, and he was asking everybody he ran across some question about, “What kind of trees are these? What are these funny little things growing out of the ground?” He’d write it all down in his notebook. Remarkable notebooks, if you’ve read any of his journals. Surprising. The poetry just came out spontaneously.

His archive is at Stanford now.

Yes. Bill Morgan, the archivist in New York, sold it to Stanford for a million dollars shortly after Allen died. Before Allen died, 1997 maybe. The Bancroft Library wanted it too, but they didn’t get it.

The sixtieth anniversary of City Lights is coming up next week. What’s happening with that? Anything special?

It’s going to be an open house. On our fiftieth anniversary we had a big event. The avenue was closed, and everything. Kevin Starr, the State Librarian, spoke, and many others.

It’s still available to view on YouTube.

This time it’s just an open house with a lot of appropriate jazz in Kerouac Alley, food and drink inside, and a lot of little separate events, poets reading. I didn’t have much to do with the planning.

You’re fortunate that you have people helping you out.

[Ferlinghetti begins signing some books for me that I brought along.] Well, I’m glad you have this one [The Secret Meaning of Things, New Directions, 1966]. You know, it’s surprising. You publish a book of poetry, and it’s like dropping it off a cliff and waiting for the echo. I’ve published some books of poetry and never heard a word, didn’t get any reviews, and no one ever said anything to me about the book. Really.