During the 1990s, contemporary art from China received increased attention outside of the country, principally in the West, through a growing number of exhibitions and publications featuring works by artists from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.1 In the late 1980s and early 1990s, either small venues or a minor part of larger exhibitions featured contemporary Chinese arts.2 The 1989 Tiananmen events, the phenomenon of rapid globalization, and numerous economic reforms introducing market principles in China suddenly attracted Western institutions’ interests in the early 1990s. These interests rapidly extended into artistic and cultural domains, and curiosity drew the organization of exhibitions and publications of artists from China. In the first half of the 1990s, exhibitions introduced contemporary art from China to Western audiences such as the touring blockbuster China’s New Art, Post-1989, curated by Chang Tsongzung Johnson and Li Xianting, that initially opened in 1993 in Hong Kong.3 Most of the accompanying exhibition catalog’s texts positioned the featured art practices in terms of political, social, and cultural backgrounds, as well as historical development. Few only included essays about artworks or artists’ practices.

In an article published in 2002, Britta Erickson highlighted that since the early 1990s, the reception of Chinese art in the West evolved under the shadows of three main issues, which appeared in Western exhibitions.4 First, the search for exoticism in “the other,” as announced by Edward Said, has been persisting in the West. Then, the violently suppressed Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 dominated the perception of China. Finally, Western art experts struggle seeing beyond the surface of contemporary Chinese art, considering it as mostly plagiaristic of Western art. Some Western exhibitions in the late 1990s distinguished themselves in their approach to contemporary art from China, apparently encouraging a more nuanced and multilayered appreciation of Chinese art. In the late 1990s, some shows introduced new angles or materials about contemporary Chinese art, such as particular themes or focuses on specific medias. For instance, Die Hälfte des Himmels: Chinesische Künstlerinnen at the Frauen Museum in Bonn (Germany, 1998) featured the works of numerous female artists, still underrepresented in the field today. Another Long March: Chinese Conceptual and Installation Art in the Nineties at the Breda Fundament Foundation (the Netherlands, 1997) also explored the specific medias of installation and performance.

Among these exhibitions, the blockbuster exhibition of the Chinese avant-garde Inside Out: New Chinese Art attracted a wide international attention.5 Traveling from New York City to San Francisco between 1998 and 1999 and then to several other countries, this exhibition was branded as “the first major [show to introduce American audiences to] the dynamic new art being produced by artists in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, and by Chinese artists who have emigrated [to the West] since the late 1980s.”6 Guest curated by art critic, curator, and scholar Gao Minglu, the show featured more than 80 new commissions and existing artworks produced between 1984 and 1998, such as paintings, installations, videos, and performance artworks. The core of the selected 58 artists consisted of the major artists of the ‘85 New Wave such as Geng Jianyi, Gu Wenda, Huang Yong Ping, Liu Wei, Long-Tailed Elephant Group, Qiu Zhijie, Xu Bing but also, to a lesser extent, younger artists such as Zhang Huan, Cao Yong, and Wu Tien-Chang.7 As numerous group exhibitions featuring contemporary Chinese arts in Europe and North America, Inside Out also claimed to be the first and most representative large presentation of the recent art production from China providing a unique space to understand “China.”8 Similar assertions had been formulated before as a common promotional sentence for Western presentations of non-Western artwork. Nonetheless, the exhibition’s singularity lied in distinguishing the artists’ places of origins: mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong that were (and still are) often considered as a homogenous ensemble despite their differences. Moreover, Inside Out not only featured the works by major actors of the avant-garde of ’85 New Wave. The exhibition was acclaimed due to the more nuanced understanding of contemporary art from China it provided to its visitors.

Wenda Gu, “United Nations Series: Temple of Heaven (China Monument),” 1998, from the exhibition Inside Out: New Chinese Art. Installation with screens of human hair. Approx. 24 x 30 x 27 ft. Courtesy of the Internet.

Fifteen years later, this article argues that the exhibition perpetuated a vision of contemporary Chinese arts framed by some general assumptions about the cultural particularism of the countries and the superiority of Western art. The local frameworks comprised the rapid modernization of the country through political and economic changes, as well as various conflicting East vs. West identities. This article focuses on and analyzes the content of the exhibition catalog as well as some reviews of the show published in Frieze and SFGate, to grasp the written art discourses at play. Doing so highlight the exhibition’s writing and editorial strategies that framed Chinese artists as the “other” rather than approached individual artists who contributed actively to international exchanges in the field of contemporary art. Finally, investigating the art discourses at play in a supposedly progressive and respectful Western presentation of contemporary Chinese art is crucial today. It allows for assessing and reflecting on current curatorial and editorial strategies implemented in exhibitions of works by so-called non-Western artists in North America and Europe.

Two main and unequal parts divide the 220-page colored catalog of the exhibition Inside Out: the writings (about 120 pages) and the full-colored image reproductions of the artworks (about 70 pages). The publication does not include any formal descriptions or in-depth analysis of the works or extensive biographies of the artists in the show. The only given in- formation about these works is located in the images’ captions (name of the artist, title of the work, date of creation, medium, dimensions, and the provenance of the work) or the artists’ three-line biographies (the artists’ dates and places of birth, their current cities of residence, and their educational background). Three chronologies of key events respectively taking place between 1967 and 1998 in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong are also included, highlighting the effort of the curatorial team to acknowledge and distinguish the different local contexts. Last but not least, the text section also gathers two introductory texts and nine essays by renowned Chinese art scholars and curators Norman Bryson, Chang Tsong-Zung, David Clarke, Gao Minglu, Hou Hanru, Leo Ou-Fan Lee, Victoria Y. Lu, and Wu Hung. Together, their essays aim at providing readers with some insights into China’s local historical, artistic, and socio-cultural contexts of the previous 30 years. For instance, in his essay Across Trans-Chinese Landscapes: Reflections on Contemporary Chinese Cultures, writer Leo OuFan Lee discusses the growing multiculturalism of China. He mentions the different experiences of inhabitants of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) according to the regions, as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Chinese communities overseas.9 He highlights the recent status of Hong Kong as China’s first special administrative region since 1997, after 156 years of British colonial ruling.

As an audience member, being aware of and understanding the specific and unique local contexts in which the artists have been evolving might seem necessary to comprehend the content, idea and formal aspect of some of the works displayed in the exhibition. However, while insisting on their political and socio-economical developments of China, the catalog does not allow audiences to draw direct connection between the artworks and their contexts of production because of the lack of dedicated analysis. Rather, the catalog frames contemporary Chinese arts as “Chinese,” “new,” and “modern”—as the title of the exhibition also suggests—determined by the recent, singular, local developments of its production contexts. As Rey Chow, cultural critic specializing in 20th-century Chinese fiction and film and postcolonial theory, declared in 1998 in her essay Introduction: On Chineseness as a Theoretical Problem:10

There remains in the West, against the current façade of welcoming non-Western others into putatively interdisciplinary and cross-cultural exchanges, a continual tendency to stigmatize and ghettoize non-Western cultures precisely by way of ethnic, national labels. […] Authors dealing with non-Western cultures […] are compulsory required to characterize such issues with geopolitical realism, to stabilize and fix their intellectual and theoretical content by way of national, ethnic, or cultural location. Once such a location is named, however, the work associated with it is usually considered too narrow or specialized to warrant general interest.

Chen Shun-chu, “Family Parade,” 1995-96, from the exhibition Inside Out: New Chinese Art. Installation with framed photographs. Dimensions variable; each photograph 29 x 24 cm. Courtesy of the Internet.

As guest curator Gao Minglu highlighted in his curatorial essay, the themes of the exhibition Inside Out were identity and modernity, focusing on the socio-politico singularities of contemporary mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Chinese communities overseas. Geopolitical realism then occurs through the usage of a specific rhetoric in the catalog, more specifically in the foreword and the introduction. Written respectively by the directors and curators of the organizing venues SFMOMA and Asia Society New York, these two texts indirectly indeed invited readers to recognize the signifiers of what they designate as “Chineseness” in the exhibition.11 As the Western curators advising Gao Minglu stated in the introduction to describe the works on view: “The complex responses of the artists to political and social changes are discussed in detail in Gao Minglu’s essays; here, it is sufficient to emphasize that the ‘Chineseness’ of these works varies enormously from artist to artist, movement to movement, and even from work to work.”12 In other words, viewers could expect to grasp this so-called “Chineseness” in the formal aspects of the artworks, as a distinguishing trait with “what came from the West.” The artworks were solely defined as responses to some internal political and social changes, rather than active artistic explorations, for instance. The unique series by the conceptual Tactile Sensation Group, entitled Tactile Art (1988) and featured in the show, is a good example. Active in the late 1980s in Beijing, China, the conceptual art group formed by artists Wang Luyan and Gu Dexin explored the possibility of creating a rational language based on diagrams that would symbolically and visually represent some usual in- formation and activities. Such materials included temperatures, sizes of nonspecific spaces, daily and customary situations (e.g. greeting someone by shaking hands), and the corresponding involved material components (e.g. hands). Until today, despite their inclusion in few major exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art,13 few in-depth studies have been produced about the group’s work over the years, either in Chinese, English, or any other language.14 By selecting them, the major Western exhibition Inside Out could be considered as progressive and inclusive of less recognized practices, specifically as the field of conceptual art in China also lacked critical analysis. Yet, what does it mean to analyze their practice through the lens of political and social events here? Is that not reinforcing the initial idea of the artists to meet predetermined expectations of “Chineseness” in art? Here, the context of the United States at the end of the 1990s comes to mind, and more specifically the contemporary studies of racial and ethnic minorities that had emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s. This field of studies had addressed the criticism that the role of Asian Americans, Blacks, Mexicans, Latinos, and Native Americans in American history was undervalued and ignored because of Euro-centric bias.15 At the time of the exhibition Inside Out, this field of studies in the United States ex- perienced numerous attacks due to the rise of the conservative movement in the country.16 In Inside Out, this framing process of contemporary Chinese arts through labeling the artworks and art practices as “Chinese” and “new” might also echo the search for an exotic “other,” as announced in the seminal essay Orientalism (1978), by literary theorist and public intellectual Edward Said. In this text, Said explains that Western writings created a romanticized system of imagery or ideas of “the Orient”—Middle Eastern, Asian, and North African societies. They attributed unalterable cultural “essences” to these societies, inferior to the West’s, which had multiple imperial and colonial implications. In these pieces of writings, the use of the term “Chineseness” may echo this notion of “the other” mentioned by Said as it catalyzes and essentializes the cultural differences between China and the West as a distinguishing trait to analyze Chinese contemporary arts.

Yet, strictly speaking, the texts included in the catalog accompanying Inside Out do not directly depict mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong in a romanticized or inferior way in comparison with Western arts. Rather, the foreword and introduction positioned contemporary Chinese arts from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and overseas communities as a fusion and even direct “multifaceted and long-standing” interconnection with Western art, and their local cultural identities and traditions.17 The use of the term “long-standing” is worth underlining; it applies differently according to mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, as the word “multifaceted” may have suggested. For example, artists in mainland China only witnessed the introduction of literature, philosophy, and art styles from the West in the 1980s, as one of the many consequences of the end of the Cultural Revolution and the attendant liberal economic and social reforms of the late 1970s.18 Inside Out catalog mainly positioned the featured works as artistic “borrowings” from the West, stating that featured artists added some new elements to Western arts (“some new twist given”).19 This line of thought perhaps implies that viewers had to consider and evaluate the relation of artworks featured in Inside Out to their Western counterparts.

Going further, this perspective may also suggest that the exhibited works could not only be innovative in relation to their own cultural contexts, reaffirming the dominance of Western concepts of modernism (the “norm”) in the contemporary art world. Numerous Westerns reviewer of the show, consciously or less so, voiced this so-called superiority of Western art. For instance, the San Francisco Bay Area-based newspaper SFGate review entitled “Signs of West in Works From the East” (1999) concluded: “On the evidence of Inside Out, [Conceptual and performance work in Western art] is the nearest thing to an international language of contemporary art.”20 Besides attempting to identify signs of “Western modernist or post- modernist influence” in the exhibited works, the reviewer argued for their inaccessibility for Western audiences, even for art professionals. The writer mainly attributed this unreachability to a lack of knowledge about the cultures and arts of the regions. This conclusion may relate back to Rey Chow’s essay Introduction: On Chineseness as a Theoretical Problem: once the non-Western location (e.g. here “China”) is named, numerous Western audiences consider the associated works as narrow or inaccessible. Similarly to the SFGate review, Frieze published in 1999 an article about the show that read, vis-à-vis Phoebe Man’s Beautiful Flowers (1996): “what seems most salient to the work is the long-standing Chinese relationship with flowers, impenetrable to Western viewers.”21 The installation consisted of a sculpture decorated with small flowers that revealed to be, upon closer look, by red-stained sanitary pads encircled by white eggshells. . . . Why did the reviewer omit to suggest questions relating to the significance of female biological phenomenon such as birth in China, and rather focused on the status of flowers?

Wang Guangyi, “Great Criticism: Tang,” 1991, from the exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989. Oil on canvas, 97 x 97 cm. Courtesy of the Internet.

Inside Out: New Chinese Art closed almost 20 years ago, yet the situation of repetitively framing so-called Chinese or other non-Western contemporary art practices according to pre- determined, existing narratives based on “regional identity” and/or “Western art’s superiority” has remained largely persistent. One example of such practice, among many, is the recent exhibition Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China (2014) on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. For its first major exhibition of contemporary Chinese art in its history, the museum selected 70 works produced in the last three decades and divided them into four sections—The Written word, New Landscapes, Abstraction, and Beyond the Brush. This exhibition framed featured contemporary artworks through the lens of tradition, emphasizing the visual traits shared between traditional and Chinese contemporary art (e.g., techniques, materials, etc.). The show failed to develop a space for appreciation of these individual artworks for their own contemporary messages and forms.

The question then remains: through exhibition making, how can we challenge preconceived ideas of so-called non-Western contemporary art practices and engage with them without stereotypes in the West? This aspect is linked to the process of translating—the practice of presenting and attempting to render the meaning of a text, an artwork, a cultural reference in another language or socio-cultural context—as it can apply to institutional and curatorial practice.

In the interview published in this issue of SFAQ, curator and critic Hou Hanru suggests creating an exhibition structure that would challenge the dominance of Western institutions while encouraging art experimentations and differences.22 In such regards, the exhibition Cities on the Move (1997–2000), which Hou curated with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, might provide a possible model of such structure.23 The entire project aimed to provide Western audiences with an overview of the urban dynamics of the Asian metropolis, through the lens of artistic projects. The exhibition traveled to six venues in Europe and in the United States24 over the course of two years (1997–1999), and invited more than 70 Asian and non-Asian artists and architects to exhibit their works. Each iteration varied the final checklist, featured art projects, and exhibition scenographies. Echoing the contexts of the always-changing nature of urban architecture and of identities of Asian cities, the scenography of the exhibition transformed the exhibition space into a living city, or vice versa, as the organizing city became the space of display. Visiting audiences could find a theatre, a train station, the sky train, the city square, the river, a cinema, a university, a church, etc. This evolving exhibition model challenged the Western-established model dominated by the white cube as an ideology and a bureaucratic practice.

Other innovative curatorial models that would challenge local institutional frameworks still are to be invented to present comprehensively artworks produced in a different socio-cultural context. An example is the not-for-profit organization Asian Contemporary Art Consortium in San Francisco (ACAC-SF) that organizes the third edition of the Asian Contemporary Art Week San Francisco 2014, from September 20th-28th, 2014. The thematic approach of the ACAW 2014 examine the notions and issues of language, cultural specificities, mis/translations, and their philosophies to actively reexamine notions of cultural and historical specificity in a global context. Such questions are key today to contemporary exhibition practices and different organizations are currently investigating dynamics of mis/translation in exhibition making and art criticism.

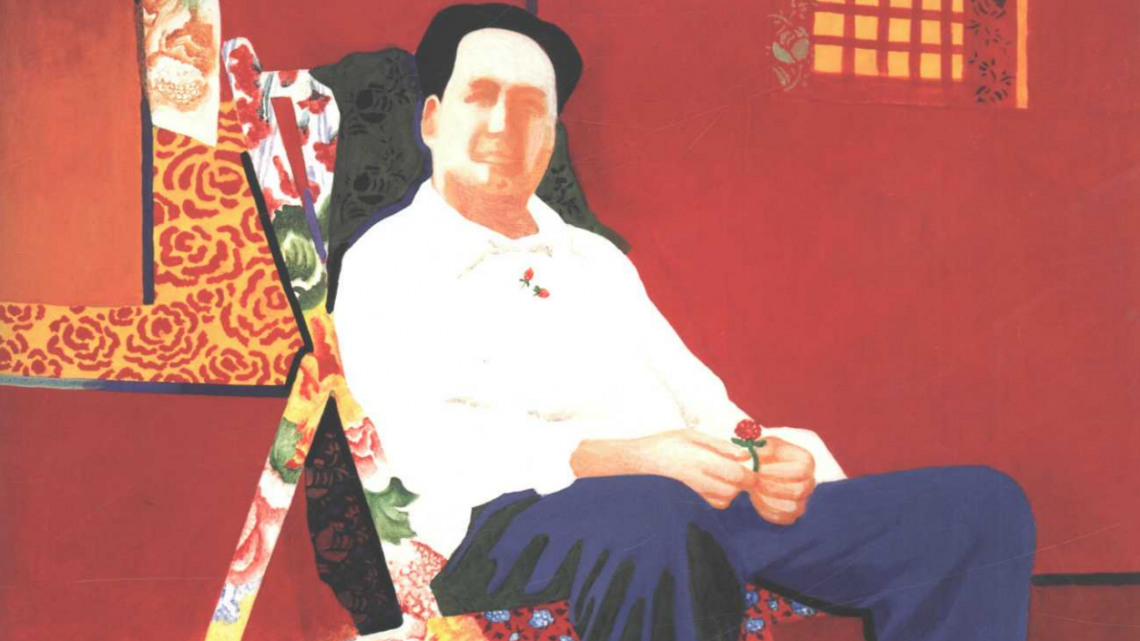

Yu Youhan, “Mao in a Colorful Lounge Chair,” 1992, from the exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989. Acrylic on canvas, 118 x 98 cm. Courtesy of the Internet.

1) Britta Erickson, “The Reception in the West of Experimental mainland Chinese art of the 1990s”, 2002, in Primary Documents: Contemporary Chinese Art ed. Wu Hung (Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 357. Examples included solo exhibitions of outstanding émigré artists such as Gu Wenda’s Dangerous Chessboard Leaves the Ground at the Art Gallery of the York University in Toronto in 1997), or group shows such as Art Chinois, Chine Demain Pour Hier, curated by Fei Dawei (Pourrieres, France, 1990), China’s New Art, Post 1989 curated by Chang Tsong-zung and Li Xianting (Hong Kong, 1993) or Cities on the Move curated by Hou Hanru and Hans-Ulrich Obrist (Europe and United States, 1997-1999).

2) Britta Erickson, “The Reception in the West of Experimental mainland Chinese art of the 1990s”, 2002, in Primary Documents: Contemporary Chinese Art ed. Wu Hung (Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 357. “In the late 1980s and 1990s, contemporary Chinese art was featured in a few exhibitions in the West, either small exhibitions at minor venues, or as minor elements of a large exhibition. In North America, for example, the first exhibitions of avant-garde Chinese art were held in colleges in the 1980s and were not widely publicized. The include Painting the Chinese Dream: Chinese Art Thirty Years After the Revolution […] at the Smith College Museum of Art (1982) and Artists from China –New Expressions at Sarah Lawrence College (1987).”

3) Venues included Hong Kong Arts Centre (Hong Kong), Hong Kong City Hall (Hong Kong), Melbourne Arts Festival (Melbourne, Australia), Vancouver Art Gallery (Vancouver, Canada), University of Oregon Art Museum (Eugene, United States), Fort Wayne Museum of Art (Fort Wayne, United States), Salina Arts Centre (Salina, United States), Chicago Cultural Centre (Chicago, United States), San Jose Museum of Art (San Jose, United States)

4) Britta Erickson, “The Reception in the West of Experimental mainland Chinese art of the 1990s”, 2002, in Primary Documents: Contemporary Chinese Art ed. Wu Hung (Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 358.

5) Marjan van Gerwen, “Inside Out: New Chinese Art,” International Institute for Asian Studies, 1998, accessed on July 7, 2014. http://www.iias.nl/iiasn/18/. Inside Out was on view simultaneously at the Asia Society Museum and the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in New York City from September 15, 1998 to January 3, 1999. The show then toured to SFMOMA and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco from February 26 to June 1st, 1999. New York City and San Francisco are two of the cities with the largest Chinese communities outside of China. Other stops included the Museo De Arte Contemporaneo in Monterrey, Mexico, and the Tacoma Art Museum in Seattle. Beginning in the spring of 2000, the Inside Out: New Chinese Art (1998) exhibition was installed in a number of prominent locations throughout Asia.

6) Vishakha N. Desai, and David A. Ross, Foreword to Inside Out: Chinese New Art (Asia Society Galleries and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 7.

7) Gao Minglu, Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art (MIT Press, 2011), 101-106. Gao Minglu coined the term “’85 New Wave” during a lecture given at the National Oil Painting Conference held by the National Artists Association on 14 April 1986, in which he introduced recent developments in art to China’s art community. Between 1984 and 1986, more than two thousand artists, among them Zhang Peili, Geng Jianyi, Gu Wenda, Wu Shanzhuan, and Wang Qiang and many others, mobilized and formed eighty unofficial groups located throughout the country; the period is designated as ’85 New Wave.

8) Exhibition catalogue Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao Minglu (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 1-8. “Inside Out: New Chinese Art is the first major exhibition to explore the impact of [momentous political, economic, and social changes] on artists in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and on those who left the region in the late 1980s. […] [The partnership between the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Asia Society NY] is crucial to articulating the organizing principle of the show: to understand contemporary Chinese art as simultaneously belonging to the international art community as well as the new “Chinese” culture.”

9) Leo Ou-Fan Lee, “Across Trans-Chinese Landscapes: Reflections on Contemporary Chinese Cultures,” in Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao Minglu (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 41-42. “41 “Whereas the term Chinese is still used as a conceptual rubric to cover these regions, on the basis of their shared written language and/or ethnic origin, it is also clear that this is no longer a unified world like the Middle Kingdom in the past.”

10) Rey Chow, “Introduction: On Chineseness as a Theoretical Problem,” in boundary 2, vol. 25, no. 3, Modern Chinese Literacy and Cultural Studies in the Age of Theory: Reimagining a Field (Autumn, 19998), 1-14.

11) Foreword and Introduction to Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao Minglu (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 1-14.

12) Foreword and Introduction to Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao Minglu (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 12.

13) These presentations ranged, among others, from Exceptional Passage – China Avant-garde Artists Exhibition at Fukuoka Museum (Japan, 1991) to China’s New Art Post-1989 at Hanart T Z Gallery, Hong Kong Arts Centre and Hong Kong Arts Festival Society (Hong Kong, 1993), and China Avant-Garde: Counter-Currents in Art and Culture at Haus der Kulturen (Germany, 1993), among others.

14) Essays in English that analyzed the Tactile Sensation Group becoming later New Analysts Group’s practice included for instance Bing Yi’s “On Wang Luyan, Chinese Conceptualism and the New Analyst Group” (2006) and the chapter on Gu Dexin’s practice, entitled “Gu Dexin: 1962.02.27” in Karen Smith’s Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-Garde in New China, The Updated Edition, ed. Karen Smith (Timezone 8, 2008). If both texts wrote about the NAG’s practice, it is worth noting that they focused on one of the NAG artists, respectively here Wang Luyan and Gu Dexin. Their authors examined the New Analysts Group as a lens through which one might understand Gu and Wang’s artistic practices.

15/16) Nelson Maldonado-Torres, “Ethnic Studies on its 40th Birthday,” 2008, University of California, Berkeley. Last accessed on July 10, 2014. http://ethnicstudies.berkeley.edu/40th/ “Black Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Women’s Studies emerged in 1968, 1969, and 1970, respectively. They are all children of a very important moment in twentieth century history: a historical moment that unfortunately has been disavowed by multiple circles, particularly, but not only, conservative ones, for the last forty years.” Today, if considered as an official part of academia, its education still remains optional in most universities in the United States.

17) Foreword to Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao Minglu (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 7. “Artists in urban centers in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong (now a Special Administrative Region of China) are expanding an artistic vocabulary that reflects the dynamic relationship between their multifaceted and long-standing connections to western forms and norms as well as ties to deeply embedded cultural identities and traditions.”

18) Gao Minglu, Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art (MIT Press, 2011), 101-106. A period of liberal economic and social reforms characterized the early 1980s in mainland China and increased openness, especially to capitalism and western culture. “This period was characterized by the most intense discussion of culture since the early twentieth century.” In the art sphere, this period led to an increased exposure to Western aesthetics, philosophy, history, and art history through the availability of publications translated from foreign languages into Chinese; art exhibitions in the country; and new experiments in mediums (such as happenings). For instance, one of the most influential books was Herbert Read’s Concise History of Painting, translated in 1983 into Chinese; the first significant Western art exhibition was a survey of Robert Rauschenberg’s work at the National Art Museum of China (Beijing, 1985). Other sources of stimulation came from open education classes in art academies such as the Sichuan Academy of Fine Art in Chongqing or Zhejiang Academy of Fine Art in Hangzhou.

19) Introduction to Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao Minglu (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 12. “In virtually every mode or medium borrowed from the West something new has been added, some new twist given.”

20) Kenneth Baker, “Signs of West in Works From the East,” SFGate, published on February 25, 1999. Last accessed on July 5, 2014.

21) Jenny Liu, “Inside Out: New Chinese Art,” Frieze, 1999.

22) See Hou Hanru’s interview by Marie Martraire and Xiaoyu Weng, this issue of SFAQ.

23) Venues for Cities on the Move included, among others, Vienna Secession in Vienna (Austria, 1997-1998), CAPC Musée in Bordeaux (France, 1998), P.S.1 in New York City (United States, 19998-1999), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebaek (Denmark, 1999), Haward Gallery in London, (England, 1999) and Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki (Finland, 1999).

24) Between 1997 and 1999, the exhibition Cities on the Move consecutively took place at the Vienna Secession (Vienna, Austria), CAPC Musée (Bordeaux, France), MoMA PS1 (New York, United States), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (Humlebaek, Denmark), Haward Gallery (London, England), and at Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art (Helsinki, Finland).