Sharon Grace

Interviewed by Terri Cohn

This interview has been pulled from SFAQ Print Issue 16.

When did you begin working with video?

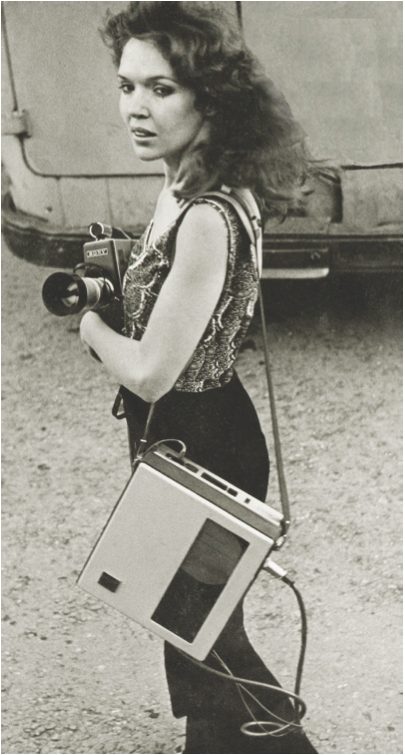

In the late 1960s I was studying psychology at Sonoma State and film and photography at the College of Marin. The film department at College of Marin acquired a Sony CV (Consumer Video) Portapak. This was the first portable video recording deck and camera. It was huge; it weighed seventy pounds. Initially no one at the College of Marin was interested in working with the seventy-pound video deck and camera. I checked it out and began taping everything including the social behaviors of people. At night I would play back the recordings from the day; studying the interactions between people. It was revealing to observe the correlation between body language, facial expressions, and speech. I was looking for deeper truths. I was in search of deeper insights into human behavior. I thought that deep truths could be found in the behaviors.

I read about a psychologist at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), who was working with film studying non-verbal behavior. I contacted him to see if he was interested in the portable video tape recording device. It was dynamic as it could record and play back images and sound instantaneously (this was 1970). Video was faster than film. The researcher was Paul Ekman, author of “Telling Lies” fame. He invited me over to his lab, where he shared some of his early research papers with me and I loaned him the video recorder and camera to explore.

How did you meet Nam June Paik and begin working with him?

I was working with a group of sound and performance artists. We created performances and staged elaborate events, complete with acoustic and electronic music which I documented with video and Super 8 film. We called ourselves Thedra Mater and then Crypilt Destiny. The name of the group changed often. I had been performing since childhood as a singer, and playing violin. Music has always been, and continues to be, a source of inspiration for me.

When CalArts opened at Villa Cabrini in Burbank, our performance group traveled south to study with Allan Kaprow. I had also heard that an artist who worked with video would be joining the faculty; his name was Nam June Paik. When I first met Nam June Paik I was carrying myVideo Portapak and—was video recording him as I walked into the room. He looked up, smiled at me, and said, “you’re a genius.” FYI Nam June referred to a number of people as geniuses; he was very generous. For the next two years I traveled with Nam June and his engineer/collaborator, Shuya Abe, helping to build Paik/Abe Video Synthesizers (including one of my own) and demonstrating how to use this innovative video instrument.

We traveled across the country to public broadcasting stations including WNET in New York, WGBH in Boston, and the Experimental Television Center in upstate New York, among others. We presented demonstrations and performances. It was collaborative, with Nam June, Shuya Abe, and many artists. Those years were also filled with stuffing and soldering circuit boards, and meeting many wonderful artists and engineers.

When I returned to San Francisco, I set up my studio on Shotwell Street in the building where Lloyd Cross and Jerry Pethick had established the School of Holography. It was a very dynamic location and exciting time. We were all engaged with techno-invention, and art.

I began traveling the West Coast to Oregon, Washington, and Canada; conducting workshops with artists. I introduced these artists to video and live video imaging processing with my Synthesizer. At that time I was also working with electronic musicians creating live video synthesized images in performances as they played their instruments. The irony is, I never liked electronic music, and because I was trained in melodic music, electronic music always sounded dissonant to me. I was always waiting for the melody, which would never come. But in the processing some of the sound through the system that I built, you could visually display these wonderful patterns that were basically the inherent geometry of the electronics of these systems. The visual display of these sounds was quite beautiful.

![[Left to right] Bill Bartlett, Sharon Grace, Carl Loeffler, Brendan O’Reagan, and Art Kleiner.Artists’ Use of Telecommunications Conference at SFMOMA, February 16, 1980.](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Screenshot-2014-04-30-11.03.021.png)

[Left to right] Bill Bartlett, Sharon Grace, Carl Loeffler, Brendan O’Reagan, and Art Kleiner. Artists’ Use of Telecommunications Conference at SFMOMA, February 16, 1980.

You would display them on a screen?

Yes, in color. Using black-and-white cameras the system would introduce color. It would take the black-and-white signal and add color burst to it. That was some of my earliest work.

In the late ‘70s I made a video piece using my synthesizer titled “Metaphors” that later won an NEA award. It is a meditative piece; I created the soundtrack by playing a Buddhist Meditation Bowl. My Paik/Abe Synthesizer is now in the Nam June Paik Art Center in Seoul, South Korea, on permanent display. Happily, it is in working condition.

At that time I was also on the founding board of the Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC). We wanted to make the tools of video media production available to the community— both artists and community activists. BAVC was initially funded with a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. Its mission was to provide artists with access to these tools.

I began working with children using my video equipment. I set up elaborate installations in public spaces and public schools. In the SF Civic Center I created an installation so children could see their own self-image in real time on a stack of TV monitors. The children I was working with were mainly from lower income families and I wanted to teach them that they could be active participants in the world of form. It was wonderful to see them recognize their own image reiterated on multiple video monitors. I heard a constant chorus of “it’s me,” “it’s me.” Their behavior changed as they interacted with their own image. From my studies in psychology I realized that this was a method of consolidating the self for these children. I continued this practice when I taught at several other schools.

How did you become involved with the conceptual artists working in the Bay Area during the 1970s?

I moved from the Mission district to a studio in SOMA. I was aware of the conceptual artists, but hadn’t really connected with them yet. Tom Marioni’s studio was on Third Street at the time. I met him and Alan Scarritt, who created an artist’s space called Site, Cite, Sight. I already knew Carl Loeffler from his alternative space La Mamelle. Terry Fox would sometimes participate in our telecommunications events.

How do you make decisions regarding the form your work will take?

I conduct an investigation, and out of that investigation comes the concept. The concept Defines the appropriate media for the realization of the piece.

How did you start working with telecommunications as a medium?

In 1977, I was contacted by New York filmmaker and publisher/editor of “Avalanche” magazine, Liza Bear, who invited me to be the West Coast coordinator for “Send/Receive,” which was to be the first coast to coast live artist satellite broadcast. It was a three-day event with Liza and her group who were in New York, on the banks of the Hudson River. Artists at the Manhattan site included Keith Sonnier, Willoughby Sharp, Nancy Lewis, and Diego Cortez. The San Francisco group included me, Alan Scarritt, Margaret Fisher, Terry Fox, Carl Loeffler, and Richard Lowenberg. Our group was at NASA/Ames Research Center in Mountain View. The first day of the event was September 11, 1977. “Send/Receive” was distributed on Manhattan Cable TV in New York. We sent our signal up from NASA/Ames into the lecture hall at the San Francisco Art Institute on Chestnut Street.

“Send/Receive,” NYC Uplink Site: September 11, 1977. Photograph by Keith Sonnier. Courtesy of the artist

It seems that this was one of the many firsts you created during your early career. Do you think being in San Francisco supported you in that?

The Bay Area has always been about experimentation and flamboyance. The proximity to Silicon Valley provided access to technical innovations, which facilitated our efforts.

Can you talk about this some more?

We collaborated with sound and images in real time with artists, musicians and poets around the world. We demonstrated the potential of the form, and the projects were great. I was motivated by the possibilities for great things to happen.

What did you do after “Send/Receive?”

In the late 1970s I began teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute, in what, at the time, was called the Performance Video Department. It later evolved to become the New Genres Department. During this time I produced “Other Unsung Songs,” c. 1978. This is an installation work made with cast stone, a military microwave dish and barbed wire. The piece expressed my concern for those who might possibly be left out of the emerging Internet.

Several of us who had worked on “Send/Receive” located compression video systems that worked over voice grade telephone lines. So we acquired a bunch of them, and sent them around to artists in the US and other countries. We created what was really the first artists’ telecommunication network. Initially the images were black and white because at that point there wasn’t enough bandwidth for color. The network was global, and we began day and night transmissions between artists, poets and performers. We called the initial group the Artists’ Prototype Network, because we knew it was a prototype and would lead to an ever-expanding network, which, in-fact, it did.

“Send/Receive,” September 11, 1977. Split-screen image New York/San Francisco. Nancy Lewis (NYC) & Margaret Fisher (SF) Photograph by Gwenn Thomas. Courtesy of the artist.

We literally created hundreds of these events. I had the system set up in the garage of my studio in the South of Market, and other artists would come over and we would participate in live events over our global network. It was 1978; the phone would ring. I’d plug the whole thing in with alligator clip leads on the telephone handset, and then suddenly whoever came by or just myself would be sitting in my garage trying to keep something going with artists presenting performances and text pieces from around the world. This was all going on before the Internet was everywhere, before smartphones, and very few people owned a personal computer (which at that time were basically glorified typewriters).

That sounds amazing.

It was, at times, it was also wonderfully overwhelming. Sometimes the events were very orchestrated and well organized, and other times they were just chaotic and wild. We had both audio and video, and it was still the 1970s. We continued with this on into the 1980s and would sometimes hold conferences and demonstrations in public venues.

The work that we produced with “Send/Receive” and the Artists’ Prototype Network shaped the form and the language of the technological paradigm that has resulted in the global connectivity model we are living in. Our desire was to connect the planet in a global dynamic conversation; we wanted everyone’s voice to become part of it.

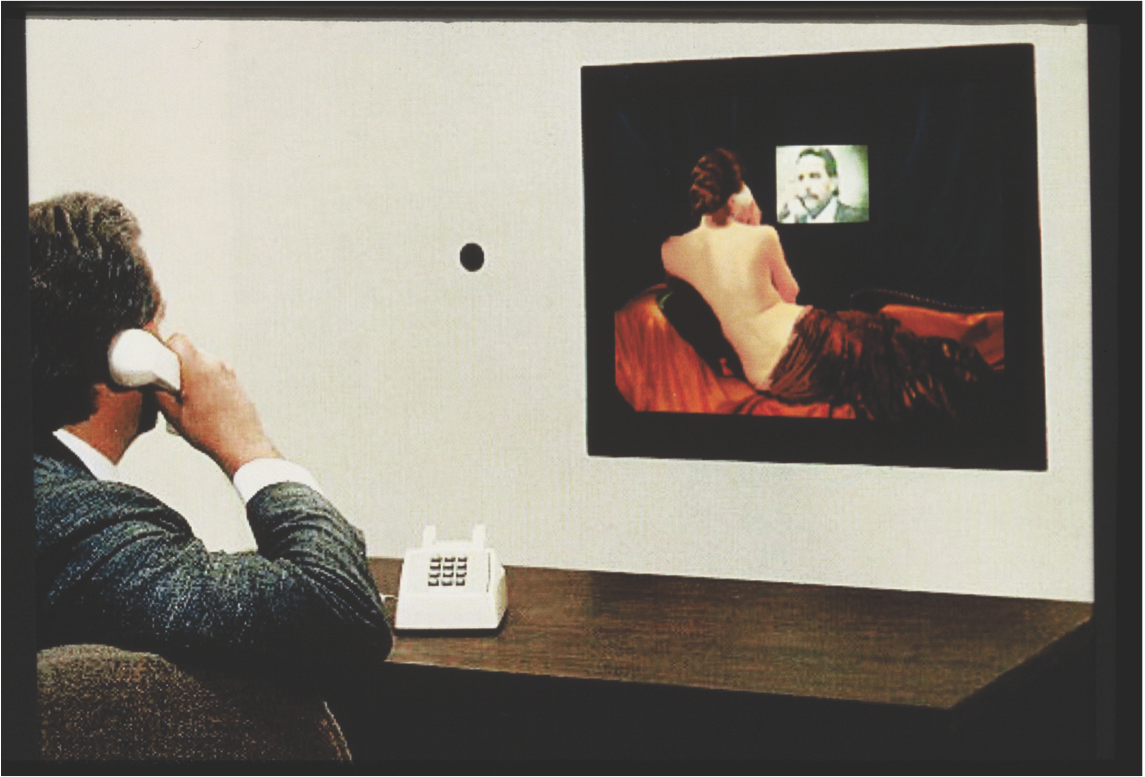

In 1990 I made an interactive video laserdisc installation that was inspired by my studies of the gaze in historical figure painting. In looking through a book on the history of figure painting, it was clear that most of the subjects were women. I wanted to reverse the gaze, and began experimenting.

What did you do?

At first I worked with both male and female subjects, but the gaze I was interested in was really about the female, and figuring out how to help her re-circulate her gaze to the renderer. Historically, she often had no control over the meaning of the whole experience, even though the meaning is her. So I set up an installation where I reversed the equation, so she is free to look, but the viewer can’t see her face, only her back. You see yourself looking, you see your own face deeply recessed in the screen, looking back at you, but the orientation is really to her face, and she’s really gazing back at the viewer. So you can understand that equation. It’s rendered in a very visible way; it’s visual geometry.

What did you call this piece?

I called the first iteration of it “Inversion,” until I discovered that it didn’t convey the intended meaning. So I changed the title to “Millennium Venus,” because I thought it needed a date marker. It was 1990. The work incorporates an interactive laserdisc programmed to respond to the viewer’s speech. The viewer/participant communicates with the program through a telephone on a desk that rings when the participant enters the room. When the phone is answered the large video display comes alive with the image of a woman who begins to talk to the participant through the phone. This work premiered at Cyberthon, a three-day event showcasing experimental work, held in San Francisco in the early 1990s. “Millennium Venus” later traveled to Madrid for an event at the Metro Opera Arts Virtual event, where she (the virtual she) learned to speak Spanish.

Do you consider that work an extension of what you were doing in the 1970s?

Yes, it (“Millennium Venus”) involves the telephone, it is about communication, but in this piece I wanted “her” (“Millennium Venus”) to talk to the viewer/participant through the technology of the interactive laserdisc. In the 1970s we had an artists’ worldwide network, we had sound, we had text, we had image, we had everything! When people ask me about that work I always refer to it as “social sculpture,” because that’s really what it was.

What are you working on now?

I have always been fascinated with the physics of gravity. Gravity is texture; the magnetic pull that we feel on this mud ball is texture. In 2008 I made a video installation working with the physics of marbles succumbing to gravity, titled “Balls to the Wall.” The gravitational traces of the marbles as they fall through space reveal the resistance of gravity and the air currents; how the marbles bounce against certain surfaces are what these drawings reveal. Once you become aware of the deep structure of forms and forces, it changes the way you think about everything. Sometimes a box is not just a box.

“Balls to the Wall,” 2008. Installation video projection, marbles, drawings and wood. Still from video projection. Courtesy of the artist.