This piece is the first in an ongoing exploration.

By Peter Cochrane

I recently saw the James Turrell retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), which opened concurrently with sweeping exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Three of the most powerful institutions on the planet operated in conjunction with one another to bring the works of one living artist to the fore, and the show at LACMA is enticing. It is a sprawling catalogue of phenomenological explorations, each room harnessing totally different aspects of perception through illusory tricks of light, deep connection to color, and participatory mental and physical immersion. In spending enough time with any given work, I couldn’t help but release a part of myself to the religiosity of the experiences. In a way that curtails explanation, dedicating myself to prolonged, intentional viewing felt like sublimating my consciousness to an interior realm, unknowingly deconstructing my surroundings until only an overwhelming field of color remained.

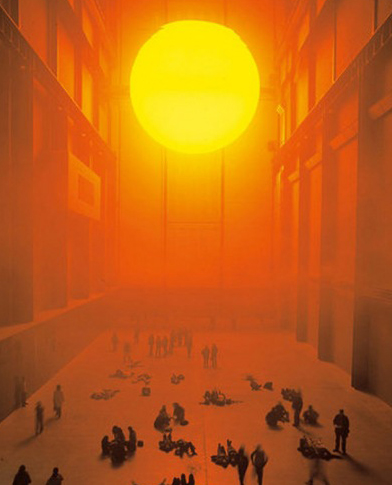

There is an aspect of abstract art, particularly that of immersive environments along the lines of James Turrell, Robert Irwin, Doug Wheeler, and recently Ólafur Elíasson, that escapes reproduction and is impossible to convey through words. It is surely akin to attempting to explain why the paintings of the Abstract Expressionists resonate within one’s self; to profess love for the way a red dot amid a swath of yellow in a Clyfford Still will always remain as abstract an emotion as the painting itself. And I think it is this inexplicable connection to a work that makes it resonate with any given person. We feel a two-way connection with the artwork that escapes reasoning, making it a private moment we are not expected to share with others. It is through this beauty—that which belongs to the sublime existence of nature—that we come to see the delicate contours of humanity that are otherwise overshadowed by unspeakable atrocities. We permit ourselves these moments of solitude to forget, if only for a beat, before returning to our realities.

Ólafur Elíasson, “The Weather Project” (2003), installation view, Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. Photo by Tate Photography.

But the grandiosity of the Turrell exhibition sparked in me an insidious thought that crept like a vine. Even as I stood alone in front of one of the largest pieces—an enormous glowing purple rectangle, an edifice at the end of a long room that danced around the periphery of my vision—I couldn’t separate from the greater context. As I stood before its phantasmal ocean, my inhalations slowing, my eyes widening with each moment in an attempt to latch onto any figment of reality in the darkness, the thick concrete walls supporting the behemoth structure began to build slowly in my mind as in some time-lapse film of their construction. Envisioned by acclaimed architect Renzo Piano, named for the building’s primary funder Eli Broad, my understanding of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at LACMA, guardian of these works of supreme escapism, shifted.

As I walked from one monstrous gallery space to the next, hosting more of Turrell’s works, I found my transcendental experience interrupted by the one prevailing fact that hadn’t fully left me since purchasing my twenty-five-dollar, reservation only ticket: this national endeavor was exorbitantly expensive to produce. While I was grateful for the museum mandated low-occupancy stroll through the galleries, I kept thinking of the fissure that was created by this economic and ideological exclusivity. These warehouses for art, diligently named after the wealthiest benefactors, were one small component of this dizzying conquest for abstraction. From the millions to build the buildings to the unfathomable amounts spent on insurance, shipment, fabrication, coordination, lighting, publication, advertisement, and everything else that keeps the operation running, I found myself unable to detach.

What I began ruminating on with increasing fervor, passing the three-dimensional model of Turrell’s magnum opus, the Roden Crater (imagine mind-bending, architecturally fascinating rooms dug throughout a mountain, illuminated variously by the sun or night sky depending on the rotation of the Earth), was the real and metaphoric value of abstraction, the role of the institutionalized museum, and the ethics of the production and consumption of abstract art.