Glen Helfand interviewed by Sarah Thibault

How did you first get interested in art and writing about art?

My interest in writing about art stemmed from wanting to contribute to a community. I actually did some study in studio art, but realized that I didn’t quite have the drive to pursue an art career. My social circle was artists, and felt that it was problematic to just go to openings on a regular basis without having some active role or giving something back. Writing was always an interest, and I was able to tap into opportunities at various alternative papers, I wrote for SF Weekly and the Bay Guardian. That led to writing for various other publications.

What was the first show you ever curated?

I want to say that it was a guerrilla show in the downstairs space of the late New Langton Arts called “Pop Life”. It was a short show that was inspired by the Artist Formerly Known as Prince, whose music I loved, and whose visual aesthetic was over the top. It was timed to coincide with his Lovesexy tour, which I just looked up and was 1988. Yikes! It was a lot of fun, and had work by Cliff Hengst, Kevin Killian, Jennifer Locke (she did a performance that involved grape soda) and others. The first show that seemed more above board was “Real Tears”, a 1992 show at the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery that responded to the arch quality of postmodern work of that era.

What made you want to get involved in organizing a show rather than responding to one through your writing?

I think my interest in organizing shows was also to be an active part of a community. But writing about shows entails a lot of looking, and often out of seeing a lot of work, I could see visual and thematic connections between artists, that weren’t necessarily being made in solo exhibitions. I’m not sure if it was a conscious effort to put myself on both sides of the critical equation, but I have always felt like it was only fair to put my own creative work out there if I was going to be critical of others. It was extremely interesting to read reviews of shows that I organized so I could have a better sense of responsibility. I know the reviews I appreciated most were ones that opened up the conversation, and pointed to things I may not have been consciously addressing in whatever project.

“HOME IS WHERE THE __ART IS”

A museum redecoration project for “Museum Pieces: Bay Area Artists Consider the de Young”

de Young Museum, 1999.

Courtesy of the artists.

How did you start working with the Asian Art Museum?

I had been in conversation with Allison Harding, the museum’s curator of contemporary Asian Art, and Marc Mayer, who coordinates public programs about collaborating on a project for a class I was teaching at CCA. During that meeting, Allison mentioned that the museum was formulating, and had funding for, a series of exhibitions focusing on Bay Area artists and did I know of curators who might be up for the project. I had actually organized a show with a similar imperative for the deYoung in 1999 (“Museum Pieces”), so I ended up submitting a proposal. I’m not sure how many others they looked at, but for whatever reason, they selected mine.

A large number of the artists in the Proximities shows are not of an Asian background. What is your interest in bringing artists from a Western background, for lack of a better term, to the AAM?

This aspect of the project has, not surprisingly, been one of the most contentious, though not necessarily from the perspective of the museum. When I was told about the original conception for the show, it was to do three solo shows, and when I asked about the artists who had been under consideration, they were not all Asian or Asian American. This surprised me, and also opened up some interesting conceptual areas to explore. Their other goals were for the shows to attract new audiences to the museum and thematically address Asia in totality. That latter charge was the most challenging–it was futile to try to marshal such a vast geographical and cultural territory into a very modestly scaled gallery space.

With the first show, the idea was really to question who has the authority (or permission) to address this theme, and to explore the idea that we all know something about Asia. Is it even possible to create an accurate picture of such vast geographical and cultural terrain? I felt most comfortable working with artists whose work I knew well, with whom I had extensive conversations through which I’d learned of knew of their connection to Asia, whether or not it was articulated in their work.

The first of the three shows, “What Time Is It There?” focused on the idea of looking at Asia from afar, from the perspective of this museum that is built upon the collection of a wealthy white American, who also had a complicated relationship with Germany in the 1930s. While I didn’t want to address this foundation explicitly, the show was also a kind of reflection of the staff, which is a diverse range of people. I was interested in showing artists who hadn’t been featured by the museum before, which quite likely would be artists who may not appear to be Asian. The bottom line is that they be smart, interesting artists making compelling work that addressed the subject.

It surprised me, though to hear some of the impassioned criticism about this, and to learn just how much people have invested in this as an institution to serve various communities who feel connected to it. The Proximities shows have perhaps questioned what those communities are—as well as the nuances of an individual’s connection to Asia geographically, ethnically, or socially. I was also working with the idea of three shows as a means of creating a continuing conversation about that idea, though perhaps it was unrealistic to expect that viewers would be able to see all three, and to see that idea while in a specific exhibition. One of the things that was also surprising to me was the number of people—of various stripes- who had never been to the museum before. In the sense of getting a new demographic in the door, the show has worked quite well.

Larry Sultan. Antioch Creek, 2008. Chromogenic print, edition of 9. 40 5/8 x 49 3/4 in. © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy of the Stephen Wirtz Gallery and Pier 24. From Proximities I at the Asian Art Museum

Lisa K. Blatt. People’s Park, Shanghai, China, May 23, 2007 9:35 pm, 2007. Photograph, mounted on aluminum. © 2007 Lisa K. Blatt. From Proximities I at the Asian Art Museum

How did you go about selecting works for the show? Did you see pieces that you wanted to include, or was the selection more about the artists that you wanted to work with based on their previous work?

I would say a combination of the two, though my approach is really to trust artists and be in dialog with them. As the deadlines were quick, I focused on artists with whom I’ve had studio conversations, from which I knew they had a connection to Asia that may not necessarily be evident in their work. A few of the artists had work that existed—Larry Sultan’s photograph, for example, and Lisa Blatt’s photos and videos of China. Of course Michael Jang’s photographs from 1973 had been around for forty years, though are only now getting more exposure. Amanda Curreri’s piece was originally shown in Korea. Andy Witrak’s “Trouble in Paradise” had existed in a smaller form—so he remade the piece at an expanded scale. Other artists made new works—I was particularly excited that Kota Ezawa and Imin Yeh were both on or about to leave for residencies in Asia when we first discussed the project, and their works were related to their time abroad. Mik Gaspay had been working on a new piece that related to the show when we began our conversation. Others made works in response to the themes.

Self-Portrait as Someone Else, 2013, by Kota Ezawa (German Japanese American, b. 1969). Two videos on monitors. Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery.

Leslie Show’s piece, “Cantra”, in the third Proximities show “Import/Export” is a mold that she has used to make objects out of sulfur. The mold is an interesting metaphor for the unseen forces that shape our perceptions of Asian cultures and a symbol for the tools that literally shape the Asian exports that we consume here in America. Imin Yeh’s “Paper Bag Project” functions in a similar way by drawing attention to the packaging of goods that we take for granted. Could you talk about this idea of invisible labor and the behind-the-scenes forces of cultural production in relation to the show?

While I think it may visually seem the most abstract, I conceived of Proximities 3 as a narrative that went from raw material, as addressed by Leslie’s piece, to complete dematerialization of labor in Byron Peters’ projection of rendered sky, which I think is the most incisive address of invisible labor. His piece was done remotely, and never existed as a tangible object—it’s outsourced imaging. I had seen Leslie’s sulfur pieces at her show at Haines Gallery and was very taken with them as a raw material. The museum wouldn’t allow us to show [them] due to conservation concerns, which resulted in her making this new work. This turned out to be an exciting prospect as it allowed for more experimentation. In terms of visibility of labor, I wanted this show to address themes that are more often pictured for the colossal scale of global trade—as in Edward Burtynsky’s photos—and look at them as something smaller and more difficult to address neatly. Imin is so wonderful at inserting sophisticated critique into projects that are inviting on the surface. Like Leslie’s piece, Imin’s is about the thing produced to encase or create another. “The Bag Project” also comments on the ways in which museums specifically present and fetishize crafts of various sorts, and the exoticization of labor.

It seems like a real challenge, borderline impossible feat for one museum to encompass all the cultures of such a large and diverse continent as Asia. One of the strengths of the Proximities shows is that you acknowledge this weakness within the museum, as well as within the outsider’s perception of “Asia,” complete with inaccuracies, voyeuristic tendencies, stereotypes, etc. For example, there are a few different pieces that are about having not been to Asia. James Gobel’s piece from Proximities 1, “You’re Gone Away But, You’ll Come Back Some Day” where he plots out an imaginary trip to the Philippines, or Rebeca Bollinger’s pieces “Everything is Everything” inspired by souvenirs that her father brought back from his business trips to Japan. Can you talk a little about that?

That futility is definitely something that I wanted to address. I also wanted to look at the ways in which any distant place can develop a fictionalized identity, even if it’s somewhere you come from. I grew up in the San Fernando Valley, of which I have romanticized visions—that American suburbia has some poetic ennui– which are usually dashed any time I visit there. I was interested in James’ work for his incredible use of and creation of pattern, but also for the theme of wanderlust that he has dealt with in numerous pieces, usually with the image of the sailor. I appreciated how his Proximities piece nudged that idea into abstraction. Like Rebeca, I also grew up in Los Angeles and also have vivid memories of imported household goods, affordable décor, and the way those objects seemed to maintain an aspect of that place, that they’d come from afar, and actually had a design identity attributed to their place of origin. The current cycle of factory production is placeless—a shirt might be made in Bangladesh or China, but its form and style are part of a generic, Westernized market. With those two artists, I would say I was interested in the rich emotional capacity that can be attached to those inanimate things. Those works are interesting to call out in considering the idea of accuracy, and the idea that there is no one singular, truthful picture of Asia.

Andrew Witrak, “Trouble in Paradise”, 2010.

cardboard, fiberglass, styrofoam, 3000 cocktail umbrellas.

5’ x 7’ x 1’

Courtesy of the artist.

Another theme in the Proximities is a critique of the way Asian culture is commoditized/ idealized, like with Jeffrey Augustine Songco’s “Blissed Out” a man meditating in an Abercrombie and Fitch t-shirt or Andrew Witrak, “Trouble in Paradise #2.” Can you talk a little about that aspect of the show?

You are on to something in linking those two pieces, as both artists used the feeling of anxiety as the starting point. Jeffrey relayed to me a narrative of being on an airplane and needing to calm himself down, whereas Andrew’s work is all rooted in apprehension and discomfort in what appears to be idyllic. Both address the fallacy of escape—beneath the garnishes of cocktail umbrellas and American-identified fashions are ideas that are difficult to contain, much less easily consume. I was also very cognizant of the fact that the museum attracts general audiences and these works both have strong visual appeal, in a sense they harness the allure of a gleaming commodity. While I never considered having them in the same show, I think they work well together, and I’m glad to hear they stuck in your mind thematically.

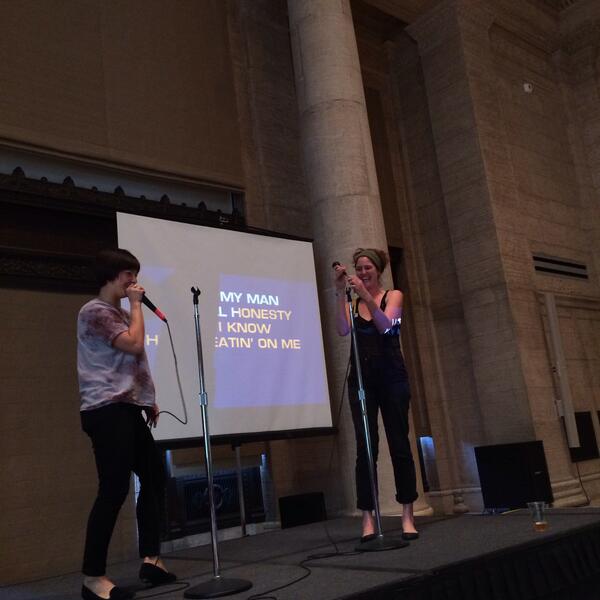

I understand you had a karaoke lounge as part of “Knowing Me, Knowing You,” the second Proximities show. I’m bummed I wasn’t able to make it. I love that idea, both as a representation of contemporary Asian culture, which is a global phenomenon at this point, and as an irreverent gesture in the contrast of the museum. I like imagining someone singing ZZ Top next to the AAM’s 3000-year-old artifacts.

But I also think there’s something important about the idea of the cover or the copy in karaoke that relates to Leslie Show’s piece. In a way, it’s the vehicle for the mass- reproduction of culture in the same way molds mass-produce or mass-reproduce objects, making them accessible to larger audiences. Or maybe that comparison is a stretch. Could you talk about why you wanted to include the karaoke lounge in the show?

That picture of ZZ Top and ancient Asian artifacts is fantastic! I have to give credit to James Gobel for suggesting that ABBA title, which I think works so well in the way that evokes relationships. And I love the irony of also attaching the image of a Nordic band whose songs are on every karaoke playbook. I’m glad you see that event as an extension of the exhibition. I was taken by Lee Bul’s karaoke projects, in which she introduced singing into the gallery space and gave it added layers of relevance, as well as Candice Breitz’s icon pieces in which she highlights the dislocated communities formed by music fans. Both of those pieces had an ebullient energy that is uncommon in art spaces. I most appreciate the way in which singing is a great equalizer, culturally and interpersonally. It’s participatory and breaks down barriers between people—it’s all in good fun, and that aspect was definitely a primary motivation for having that event. I’m not sure it’s true, but apparently karaoke hasn’t happened often in the Asian Art Museum. There’s something so wonderful about having a mic in hand and channeling the thrill of being on stage even if you can’t carry a tune. I suppose we could have staged the karaoke lounge for “Import/Export” as well, though in this case, more than the idea of the copy, I was most interested in the convivial nature of the form. It turned out, though, that we had a pretty intimate group that afternoon as the Bay Bridge was closed that weekend. And there is something odd about doing karaoke in the afternoon.

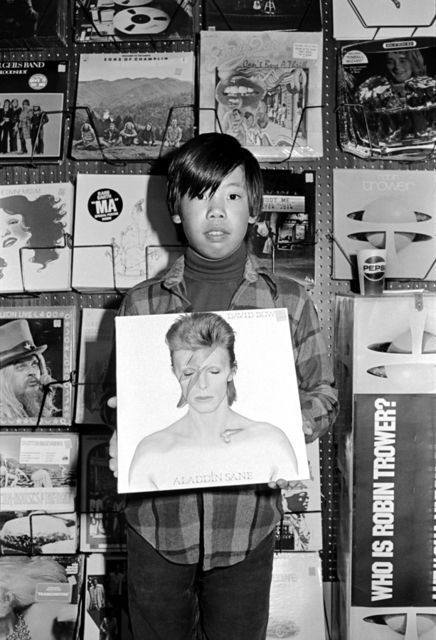

Michael Jang

Untitled, from the series The Jangs, 1973

Gelatin silver print

14 × 11 in, 35.6 × 27.9 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery. Photo: Stephen Wirtz Gallery.

What surprised you about putting together this show? Any unexpected connections or pieces come out of the curation that you hadn’t anticipated?

The most surprising aspect was the multi-part exhibition and the logistical and conceptual concerns. It was an unknown if people would see all or one of the shows, and how autonomous would each be. I also was able to think more about things in between, which was a rewarding process.

On a visual level there were a lot of unexpected moments. The way the shows unfold in the galleries created some wonderful visual connections – in the third show, Imin Yeh’s video monitor is positioned on a wall that directly backs an educational video on craft in the gallery next door, and similarly, a series of photographs of Korean Moon pottery depict white ceramics that have a strong relationship to Rebeca Bollinger’s porcelain pieces. And I never expected that any show I’d do would have a museum banner. To see Michael Jang’s photograph of his cousin holding David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane album was a real thrill. That and being able to work with artists I so admire.

Michael Jang

Chris in Record Store, from the series The Jangs, 1973

Gelatin silver print

11 × 14 in, 27.9 × 35.6 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery. Photo: Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Is there anything else you would like to add about the exhibition?

Just that I hope people get to see this third show, and that hopefully it will open up opportunities for other curators to work in this site.

Proximities 3: Import/Export is on view through February 23, 2013.

For more information visit the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

Previous contributions by Sarah Thibault:

–SFAQ Review: “The Optimists” group exhibition at Stephen Wirtz Gallery, San Francisco.

–SFAQ Review: “Beatnik Meteors” group exhibition at di Rosa in Napa, CA. Curated by Amy Owen.