I want to try to connect the aesthetic or formal aspects of art to “queerness”—a preferred term for many in my generation because it speaks to an unstable subject position aimed at dismantling all naturalized conceptions of being in the world. Because this is essentially a sensibility, I recognize any formal connections as deeply historical. The critical work of “queer aesthetics” is not predicated on the sexual identity of the artist with any sort of essentialism, but rather refers to engaging with our (already) politicized ways of being.

Formal language does not suddenly emerge, as though out of Zeus’s head. Every aspect of a work of art mobilizes a chain of associations that situate it in the world. There is nothing inherently “male” about metal as a substance, but none-the-less industrial fabrication and large metal sculptures have been historically coded as “masculine.” Artists can complicate, undermine, and renew such inherited preconceptions, but they cannot pretend they do not exist. (I think here is a space for a perverse re-engagement with Iconology: the iconology of material imagination…)

Today’s formal language of queerness evolved from feminist art, which sought to reclaim materials and experiences not historically valued in the white-hetero-masculine system. I would argue the qualities that made Carolee Schneemann’s films intolerable to (male) structuralist film-makers—”the personal clutter, the persistence of feeling, the hand-touch sensibility, the diaristic indulgent, the painterly mess, the dense gestalt”—are still the elements that define queer aesthetics in various ways, just as the cultural structures Schneemann set herself against continue.

Recently artist Colin Self said “If you are not queer, you are not paying attention,” meaning that those who don’t question larger social-political structures of gender and race are comfortable with their place in the system and not paying attention to the very real inequity all around them. You either reaffirm the status quo in a thousand tiny instances throughout everyday life, or, you denaturalize the performance—you queer it.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge described the “cut-up” as such an act of queering: “our concept of what we interpret as “reality” is completely malleable. And if it’s malleable then anyone can sculpt it. A lot of our war has been to help others realize they can sculpt it themselves by using tools as simple as cut-ups to reveal the secret war in language, showing how easily we are being manipulated to become consumers.” I see queering as refusing to reaffirm the dominant power structures as natural or inevitable and to strive to envision and construct other possibilities.

What I like most about Self’s phrase “If you are not queer, you are not paying attention” is the possibilities it opens for talking about perception in art. Recently I was a guest critic at the Bruce High Quality Foundation University. As I was situating formal aspects of a students work within a queer language another instructor chimed in: “But this painting has as much to do with Richard Tuttle, and he isn’t gay!”

As a way of answering: A TALE OF TWO DICKS

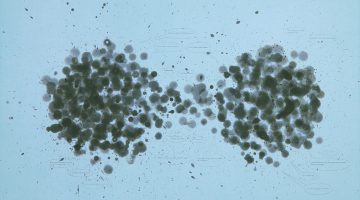

It seems stupid to compare the sculptures of Richard Serra and Richard Tuttle—the former epitomizes a performance of dominant patriarchal masculinity while the later embodies a kind of aesthetic queerness, but I think side by side they communicate how these sensibilities become visualized in matter without talking about “subject matter” (the dominant mode for identifying/discussing queer art).

Serra’s large pieces of rolled steel are industrially produced and show no trace of the artist’s hand as maker. They are so many times larger than the human body in weight and scale. They overpower you, impose themselves on you. And, you are supposed to feel threatened, knowing that they are not secured: they could kill you. They relate to ship building, engineering, industry—historically male contexts. Their relationship to their site is always as an intrusion with no real considerations of the location’s specificity. When we talk about “Tilted Arc” (1981) as important in public art it is generally related to censorship—that it was unfairly removed because of protests by people who didn’t understand “art”. Perhaps they understood the experience of it too well: as a rape, a non-consensual colonization of an open plaza bisected so it can only be experienced on Serra’s terms.

By contrast Tuttle’s sculptures are fragile, often non-art materials that bear their maker’s hand. Not only do they not impose themselves on you, they extend an invitation of equality, scaled to your body. Importantly they always recognize their contingency on the specific spaces they inhabit, asking you to perceive yourself in the space in fresh ways. Discussing Serra, Tuttle said: “When you look at Richard Serra’s sculptures at Larry Gagosian, where are you? You’re nowhere. That’s what he’s saying.”

Sculptor and performance artist Gordon Hall theorized a queer engagement with minimalist sculpture in a paper given at CAA last year. Their own sculptures attempt to embody these ideas and are specifically scaled to domestic objects that slide between references to an “audio speaker” “a table” “a stool”. They preform their “being made by the artist” which is important to them. This quality brings to mind Tuttle’s distinction between Agnes Martin’s paintings and a mechanically produced grid: “the difference between the loved and unloved line.” It is interesting that Hall is attempting to reclaim Minimalist formal language to engage types of embodiment never envisioned by its original macho practitioners.

(Aside from my discussion of “queer aesthetics” which attempts to link strategies of queerness to visual experience, there is a whole other matter of “queer misreading” with artists like Nayland Blake telling me: “One of the things that is never really discussed about Richard Serra’s work is how cruisy it is. It’s all hanging out at the docks, people looking at each other, and that is a very different read. The surprise and allure of those spaces is something that is never really talked about but is palpable in the experience of his sculpture.”)

All of these artists are engaging with issues of embodiment and perception in art contexts, and all happen to be white. I think the most important extension of these deconstructions happening in NYC are outside of the gallery, in the fertile intersection of night life and performance art that The House of Ladosha has been masterfully cultivating, along with a rich network of other art families like Chez Deep and 1:1. Juliana Huxtable is one of the most articulate figures on the scene, addressing the value structures that make certain practices legible as “art” and others dismissed as “night life”, a division heavily connected to race, class, and sexuality. (I am looking forward to sharing my extensive conversation with Juliana on this!)

There is much here to continue unpacking together through making and talking and playing together and that is our fun…

—Contributed by Jarrett Earnest

My full conversation with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge can be found here.

My full conversation with Nayland Blake can be found here.

Gordon Hall’s Paper “Object Lessons” here.

Juliana Huxtable’s tumblr here.

The Tuttle conversation with Bob Holman excerpted above can be found here.