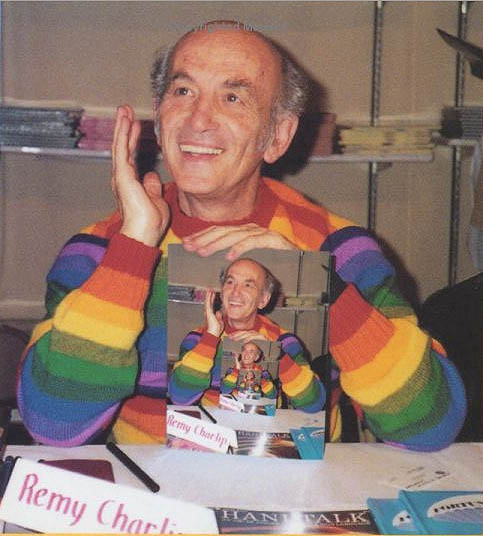

By John Held, Jr.

Remy Charlip was born (1929) and raised in Brooklyn, New York, studied textile design in high school, and graduated from Cooper Union School of Fine Arts (New York, NY) in 1949. He thought he couldn’t become a painter, as he didn’t have anything to “say.” Reflecting upon those years, Charlip has written, “Little did I know what you ‘say’ happens after you work for a while. I decided that I wanted to be a dancer, because they seemed to be ‘free spirits’ to me, and I wanted to be a ‘free spirit’.” 1

The decision lead him to a fellowship in dance at Reed College, Portland, Oregon, where he designed sets and costumes for Bonnie Bird, an early influence on John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Charlip danced in two of Bird’s productions, “The Marriage at the Eiffel Tower,” by Jean Cocteau, and “The Only Jealousy of Emer,” by William Butler Yeats. Both of these works were accompanied by music composed by Lou Harrison.2

In a turn that was to influence the course of his life, Charlip and Harrison established an enduring relationship, initially resulting in their living together in New York. Harrison, who was beginning to establish himself as major figure in experimental music, introduced Charlip to the post-war New York avant-garde. “At the time, I thought there were probably maybe a hundred interesting people in the world and I knew them all,” Charlip later quipped.3

Not the least of which were John Cage and Merce Cunningham, two friends of Harrison’s who had just returned from fellowships in Rome. “When Merce found out I was a calligrapher, he asked me, ‘Would you do a flyer for me? How much would you charge?’ It was my first commissioned job. A teacher at Cooper Union said, “Don’t do anything for less than twenty five dollars.’ I gathered my courage and asked for fifty dollars. It was the last time I charged Merce for anything.”4

Shortly, Charlip found his way to Cunningham’s studio for lessons and rehearsals resulting in Charlip’s return to his alma mater on November 24, 1950 to perform with Cunningham, Rachel Rosenthal, Sudie Bond, Marianne Preger-Simon and others, in “Rag-Time Parade,” accompanied by John Cage on piano. Charlip was to dance with the Cunningham Dance Company for the next twelve years, as well as contribute graphic and costume design.

“By the fall of 1950,” writes fellow Cunningham dancer Carolyn Brown, Charlip, “was performing Merce’s choreography and beginning to design costumes and properties, to make masks, and to perform any task of an artistic nature that needed doing.”5

As no one was salaried at this embryonic stage of the Cunningham Dance Company, Charlip performed with other groups, including that of Jean Erdman, a Martha Graham dancer with Cunningham and wife of famed mythologist Joseph Campbell. Charlip contributed set and costume design for her January 28, 1951 engagement at the Hunter Playhouse (New York), for which Lou Harrison provided music.6

A highlight of this period was Charlip’s choreography for the first New York production of The Living Theater, “Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights,” at the Cherry Lane Theatre on December 2, 1951. A reviewer seemed startled by the “intermedia” of The Living Theater, but had high praise for Charlip. “As the viper, Mr. Charlip exploited his plie and port de bras in slithering style to its utmost. This was neither a ballet nor a dance. Living Theatre, please give your choreographer a chance to show what he can do in your next one?”7 The Living Theater, guided by Judith Malina and Julian Beck, were acclaimed a decade later as one of the most experimental, and notorious, theater companies in the world.

A transformative era in Charlip’s life was his periodic visits to Black Mountain College, in Asheville, North Carolina, from 1951-1953. Currently regarded to be the nation’s most successful and influential art school, an “American Bauhaus,” at the time BMC attracted a seemingly bottomless pool of vanguard artists that were to influence the course of American post-war art: painters Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Joseph Albers, Franz Kline, Wilhelm DeKooning; poets Robert Creeley, Jonathan Williams, M. C Richards; filmmaker Arthur Penn; architect Buckminister Fuller; sculptors John Chamberlin and Ruth Asawa; and musicians John Cage, David Tudor, Morton Feldman and Earle Brown.

Lou Harrison had taught there and encouraged Charlip to visit, which he did Thanksgiving 1951 with musician/composer David Tutor and poet M. C. Richards, missing one of the doors on the car. He returned for three summer sessions, the last as artist-in-residence with Merce Cunningham and dancers, which solidified the founding of the Company.

In August of 1952, an event occurred, a crescendo in American cultural history, due in no small part to the confluence of artists in different mediums gathered in the isolated BMC landscape. Regarded as the first “happening,” it became a milestone in performance art, a brilliant mix of different artistic mediums by strong personalities intermingling in space and time. John Cage lectured on a ladder, timing out the subsequent events; David Tudor played piano. Charles Olson and M. C. Richards recited poetry; Nick Cernovich projected film; twenty-six year old Robert Rauschenberg operated a phonograph; Merce Cunningham moved amidst the audience chased by a barking dog. The impetus sprang from M. C. Richard’s first English translation of Antonin Artaud’s, “Theater and its Double,” which was circulated among the BMC community that summer. “This,” Cage later stated, “was extended on this occasion not only to music and dance, but to poetry and painting, and so forth, and to the audience. So that the audience was not focused in one particular direction.”8

On every seat, audience members found a program for this first “Happening,” printed by Charlip. “I did that little program on cigarette paper, and I got the smallest type and I was using tweezers to put the type together and…it was on this size paper, and I put it in the press…I made about a hundred of them and all together they made a stack about this high…I put an ashtray on every chair, and I put tobacco and the cigarette paper so that people could roll the cigarette and smoke it during the concert.”9

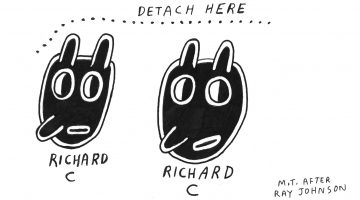

The artists who Charlip met while attending BMC formed a foundation of friendships he maintained throughout his life. He encouraged Nicholas Cernovich to take up lighting design, which the latter put to use with the Cunningham Dance Company. Ray Johnson, the inscrutable master of Mail Art, was partial inspiration for Charlip’s innovative “Air Mail Dances.” Norman Solomon, a chronically underrated painter and photographer, was a frequent New York companion of Charlip in the fifties, later residing in the San Francisco Bay Area, near former BMC students Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier.10

As if BMC was not enough, Charlip received continuing post-graduate work from 1956-1961 in the back of a Volkswagen Microbus driven by John Cage, navigated by Merce Cunningham, enlivened by Robert Rauschenberg, with traveling companions Nicholas Cernovich and dancers Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Marianne Preger-Simon and others. Writing with fifty years of hindsight, Carolyn Brown in “Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham,” (Knopf, 2007) wrote, “…our focus was nevertheless single: art and life. No separation. John’s (Cage) credo -accepting the multiplicity of things- was actively lived in the VW days.”11

Throughout this period of the mid-fifties, immersed in unpaid rehearsals and performances with the Cunningham Dance Company, Charlip supported himself by involvement in a “multiplicity of things.” His graduation from Straubenmüller Textile High School (1946) prepared him for freelance assignments in textile design, a skill he applied equally to costume design for the Cunningham Dance Company, The Living Theater and Donald McKale and Company. His graphic design skills, honed at Cooper Union, enabled him to secure steady work designing book jackets from publishers like Doubleday, Corinth Books and Harvest Books, for works by Virginia Woolf (“Jacob’s Room & The Waves”), Diane Di Prima (“Dinners and Nightmares), and dancers Irene Castle (“Castles in the Air”) and Ted Shawn (“One Thousand and One Night Stands”).

“When I was twenty, I slipped and fell on some gook in the kitchen of a summer resort where I was working as a waiter. During the week it took for my sprained ankle to heal, I decided never again to work at just any job, but to find ones in which I could develop my special talents. So I took my portfolio around to get commissions to do artwork. Although I did whatever people asked – book jacket designs, textiles, lettering – I became by own boss and was soon brave enough to do work that was self-generated. I thought up projects and carried them out.”12

In 1958, friends encouraged Charlip to join an adult theater group for children, The Paper Bag Players. The longest lasting theater company for children in North America still in existence, The Paper Bag Players earned Charlip his first Obie Award (Off-Broadway Theater) from the Village Voice for co-founding and direction of the theater company. “… we used ordinary things from around the house. We stuck our four heads in four holes cut in an old chenille bedspread for an four headed sea monster, we cut a dragon out of a big refrigerator box, used a blue plastic shower curtain for water, made a princess costume out of an old lace curtain, used wax paper for hair and aluminum foil for a crown. We wanted to inspire children to improvise.”13

This improvisational approach was previously displayed in Charlip’s first book for children, “Dress Up and Lets Have a Party,” published by Young Scott Books (New York) in 1956. The contract for the book, signed the previous year, was witnessed by Merce Cunningham.14 Young friends gather for a party wearing things from around the house: a purse for a hat, a lampshade for a tutu. Bridging the art/life divide, Charlip named the book’s characters for his personal acquaintances: Ray (Johnson), Carolyn (Brown), John (Cage) and Vera (Williams).

In the spirit of collaboration, born of personal proclivity and the process of dance, Charlip designed a 1958 book, “What is the World?” with contributions from John Cage, Ray Johnson, Norman Solomon, Frank O’Hara and James Waring, among others.

What began as a sideline has became an illustrious career. Charlip has gone on to author or illustrate over thirty books. “I continued to dance with Merce, Jean Erdman, Katherine Litz and Sabina Nordoff. I also continued to do children’s picture books. One of my favorites, “Arm in Arm,” (1969) won several Best Picture Book of the Year awards from Bratisalva Book Fair, and as one of the Ten Best Illustrated books of the Year by The New York Times. Later, “Thirteen,” (1975) and “Handtalk Birthday,” (1987) made that list as well. “Thirteen,” was chosen best picture book by The Horn Book/Boston Globe. “Handtalk,” (1977) was given the Christopher Award, and “Harlequin,” (1973) received the Bank Street School of Education Award. Other favorites are “Fortunately,” (1964), “I Love You,” (1967), “Sleepytime Rhyme,” (1999), and “Little Old Big Beard and Big Young Little Beard,” (2003). Each book had a different topic, style of writing, painting and structure suitable to it’s subject.”15

Charlip worked with some of the giants of the industry, including Ruth Krauss, with whom he collaborated on “A Moon or a Button,” (1959) and “What a Fine Day For,” (1967). He also illustrated works for Margaret Wise Brown, birthing classic children’s works, “David’s Little Indian.” (1956), “The Dead Bird,” (1958), and “Four Fur Feet,” (1961). In April 1997, Charlip was honored by The Children’s Literature Center in the Library of Congress, for his distinguished career in the field, during ceremonies coinciding with his exhibition, “A Celebration of Remy Charlip.” Two years later, The San Francisco Public Library mounted an extensive exhibition and program, “Remy Charlip’s World: Books into Theater/Theater into Books.”

His play adaptation of Krauss’s “A Beautiful Day,” won him a second Obie Award in 1966 for “Distinguished Direction.” A reviewer for “The Village Voice” mused, “Watching the Saturday night performance I found myself thinking, several times, ‘Remy Charlip is a genius’.”16 The Judson Memorial Church production was one of many theatrical works he did for the Judson Poet and Dance Theaters, one of the most innovative spaces for contemporary theater and dance of the era.

Charlip was also working at other New York avant-garde venues including Café La Mama, The Joyce Theatre and Dance Theater Workshop. He did the sets and costumes for Kenneth Koch’s, “Bertha,” at the Cherry Lane Theater (1962), and designed sets, costumes and provided choreography for Paul Goodman’s, “Jonah,” at American Place (1966). Charlip contributed make-up to a segment of Jean-Claude van Itallie’s, “American Hurrah,” at the Pocket Theater (1968). That same year he appeared with Andy Warhol and Edward Albee at the Village Gate, as well as designing costumes for a Merce Cunningham and Dance Company production of “Field Dances,” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

His growing acclaim as a dancer, choreographer, costume designer, illustrator, and director was beginning to be recognized in the academic world. “People who saw what I could do started to commission works, or ask me to teach farther afield. I traveled anywhere anyone asked me to go.”17 He was asked to participate in “Spring Dance Courses, Choreographer Theatre,” at the New School for Social Research (New York) from 1967-1969. Concurrently, he became Head of the Children’s Literature and Theatre Department at Sarah Lawrence College from 1967 through 1971, where he taught a “Workshop in Making Things Up.”

Charlip went on to become a Joseph E. Levine Fellow at Yale University (1968-1969), a Hadley Fellow at Bennington College (1976), a Visiting Artist Resident at Harvard University (1982), and John Adams Distinguished Visiting Professor at Hofstra University (1991). Additional academic opportunities presented themselves as a Regents Lecturer at the University of California, Santa Barbara (1989), and The San Francisco School District Arts Education Project (1994-1995). “All my life I’ve taught that each person is unique, living their own version of an artist-dancer-writer-singer-painter-musician. One way for me to share that special balancing act with others is to take each art separately and present it as simply as possible, without the hocus-pocus and snobbery, so that everyone can see how it’s done.”18

Charlip’s teaching activities and residencies extended beyond the classroom and into the world. He directed The National Theatre for the Deaf for two years (1970-1971), working with the actors in the creation of two celebrated works. In 1972, he directed the London Contemporary Dance Company, followed by a residency with The Scottish Theatre Ballet Company the following year and the Welch Dance Theater in 1974. That same year he was in Sydney, Australia, with the New South Wales Dance Company, before moving on to Caracas, Venezuela, with the Caracas Taller De Danza in 1975.

Previous to this, he was asked to participate in Robert Rauschenberg’s Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) project, which undertook the programming at the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion at the Osaka World’s Fair in 1970. Charlip choreographed and performed in the opening ceremonies, presenting “Homage to Loie Fuller.” This was but one of three separate trips to Japan, where seven of his children’s books have been published.

His services have been requested throughout the United States, as well as his more far-flung venues. He has choreographed commissioned works for The Joffrey Ballet (1968), Next Wave at the Brooklyn Academy of Music Opera House (1984), The Metro Theater Circus, St. Louis (1980), Rep West, Santa Barbara (1988), The Oakland Ballet (1994), and for many universities including Stanford and Mills College.

Several of these commissions have included dances based on his friendships. For Lucas Hoving, a dancer for many years with the José Limon Dance Company, he created “Growing Up in Public” (1987). In 1995, Charlip choreographed, “Ludwig and Lou,” for the Oakland Ballet, an homage to his long and continuing friendship with Lou Harrison.

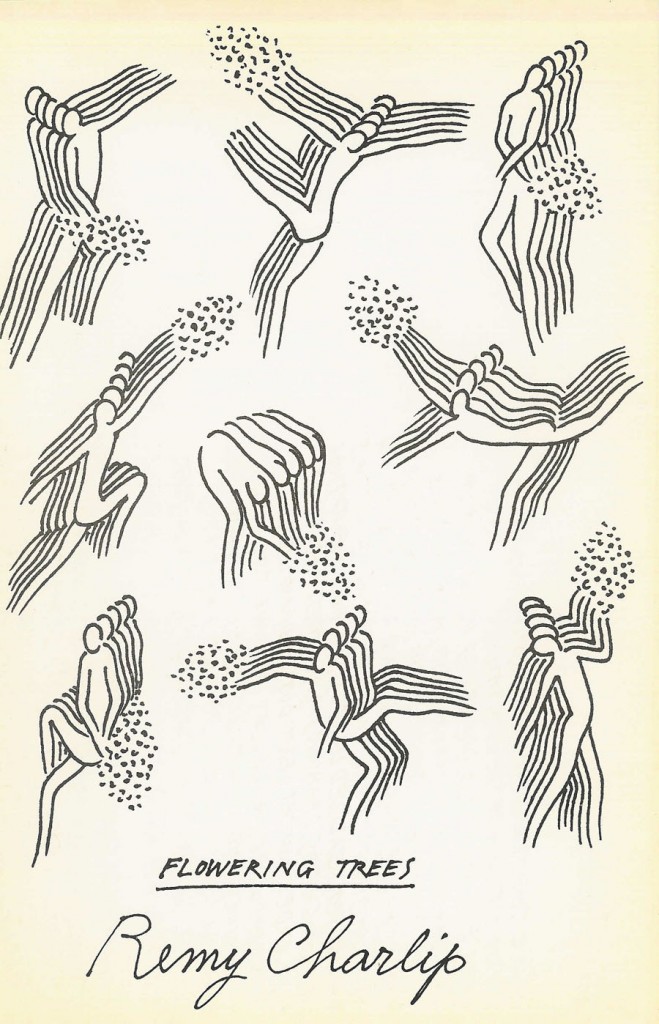

As if his constant travels both internationally and domestically were not enough, Charlip found another way to impart his creativity and choreography in the creation of “Air Mail Dances.” Inspired by the mail art of Ray Johnson, and necessity, Charlip’s tardiness in creating a choreographic work for Parisian resident Nancy Green, resulted in mailed, “Instructions from Paris,” in 1971.

In March 1976, Charlip was quarantined in Australia, unable to work with The New South Wales Dance Company in Sydney, Australia, as planned. From a detention cell in Sydney, Charlip drew dance movements, from which the dancers were to create the transitions. News of the quarantine and the innovative intellectual escape from conventional dance choreography made international headlines. “His Art Bounded Prison Walls,” announced the Sydney Daily Telegraph. “Children’s Book Author Gets Unexpected Rest…In Quarantine!” proclaimed a press release by his American publisher. The New Yorker carried the story in it’s, “Notes on People.” The New South Wales Dance Company, undeterred by their visiting choreographer’s incarceration, proclaimed in a press release, “Government Responsible for Creation of New Art-Form.”

“I have choreographed hundreds of dances in the usual way by being there in the same room at the time of choreographing. With a new form I invented called ‘Air Mail Dances,’ I send a drawn dance score in the mail, to soloists and companies all over the world. They interpret the 20 to 40 figures in different positions that I’ve drawn on a single page of paper. The dancers then make the transition from one drawn position to the next, thereby finishing half of the dance. In the past dance notation was used ‘after the fact’ to be able to remember, or re-construct a dance already finished. ‘Air Mail Dances’ are ‘before the fact,’ the same way one uses a new musical score, or play script.”19

Another postal inspired work was Charlip’s collaboration with Donald Evan’s on a book project, “Postcards to Gopshe.” Evans’ was an inspired artist, creating imaginary worlds through the medium of postage stamps, which he created in meticulous watercolor. Correspondence between the two, source materials, notes and page layout, exist in Charlip’s archives, although the collaboration was brought to a halt by the untimely death of Evans’ at age 32 in 1977. “I love to listen to other peoples’ ideas and work methods, their histories, dreams, fantasies,” Charlip has stated.20

“I’ve always felt like an outlaw. But there is something in that feeling that allows identification with the disenfranchised, with children, with the un-macho.”21 One of Charlip’s great strengths as an artist is this ability to identify and express the hopes and desires of those shunned by the mainstream. His work with the National Theatre of the Deaf had a profound effect on him, resulting in a biographical dance, “Glow Worm,” which was presented as part of the WGBH-Boston, program, “Dances by Remy Charlip,” in 1977. He has also collaborated with Neil Marcus, a dancer who uses a wheelchair, in a 1995 work, “The Art of Human Being.” He has committed himself to children, not only through his books but through book readings and conducting dance and creativity workshops for young performers and students throughout the country.

As a gay man, he has been tireless in promoting messages of human dignity and was nominated in 1983 for the Stonewall Awards with Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, Arthur Tress and others. “Artists have to take courage in each other. What they’re doing will eventually save somebody’s life. Literally. The physical and emotional life. The intellectual life. Artists can keep someone from being depressed or give you an idea about how to live your life in another way. That’s the thing I want us to remember.”22

A man of such broad vision and diverse talent and experience, Charlip becomes hard to pigeonhole, even by himself. “I did my first children’s book in 1956, so a child who was 10 then…a parent now 60 or over, approaches me with pleasure and admiration. I used to put down those early books as not being as ‘serious’ as my dancing. With my picture books becoming best-sellers and receiving grateful appreciation form a large number of librarians, book-sellers, parents, and children, I have had to re-evaluate my work and add to my self-image of dancer, choreographer, costume and set designer, one of educator and picture-book artist and writer as well.”23

Despite a long career in the arts, capped by lifetime achievement awards and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2005, a humble Charlip remains ambiguous about his accomplishments. “Please don’t think of yourself as an underdog,” Lou Harrison wrote Charlip in 2000. “…you are very famous, much loved and admired big time. This makes you an Overdog, you know.”24

1 Mary Emma Harris, “Black Mountain College Project: Charlip Interview.” February 23, 1998. Page 24.

2 “This Summer on Campus.” Reed College, Portland, OR. June 19-July 29, (1949).

3 Harris, page 14.

4 Remy Charlip. “Narrative of My Career and Accomplishments.” April 2005. Page 1.

5 Carolyn Brown. “Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham.” Knoph, New York, NY. 2007. Page 88.

6 Program. “Jean Erdman and Dance Company.” Hunter Playhouse, New York, NY. January 28, 1951. Merce Cunningham, guest artist. Lou Harrison, conductor. Charlip contributes costume design and sets for “The Fair Eccentric, or the Temporary Belle of Hangtown.”

7 Review, “Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights.” Dance, January 1952.

8 Richard Kostelanetz. “Conversing with Cage.” Routledge, New York and London. 2003 (Second Edition). Page 110.

9 Harris, page 10.

10 “Black Mountain College Reunion: Message for the Future.” M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, CA. March 6-7, 1992. Charlip on program with Asawa, Dawson, Harrison, Noland, Richards, et al.

11 Brown, page 341.

12 Margaret Tadesco. “Remy Charlip.” Less Hot Air on Dance (Brooklyn, NY), Summer 1992. Page 8-9.

13 Charlip, page 2.

14 Contract. Charlip and William R. Scott, Inc., New York, NY. July 22, 1955.

15 Charlip, page 2.

16 Michael Smith. “Theatre Journal: A Beautiful Day.” The Village Voice, December 16, 1965.

17 Tadesco, page 9.

18 Ibid., page 6.

19 Charlip, page 3.

20 Tedesco, page 8.

21 Ibid., page 10.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Charlip Archive. Alcove Boxes, Drawer 5 (3 of 3). Folder 9.