“Tables of Contents:

Ray Johnson & Robert Warner: Bob Box Archive”

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

University of California, Berkeley

January 27-May 20, 2012

Lectures by:

Robert Warner, January 27

Dickran Tashjian, April 18

Ray Johnson has become a cult hero, in large part due to his posthumous film portrait, “How to Draw a Bunny.” During his life (1927-1995), he was known as, “the most famous unknown artist in New York.” Those of us who knew him when…when no one else did…we treasured him. We knew he was the real deal and an inspiration on how to conduct an artful life.

Purposely avoiding public recognition in life, Johnson knew the art world in detail, having attended Black Mountain College, trained by Josef Albers, befriended by John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Ruth Awawa, et al.

Johnson was generous in sharing his friendships with others. In the late 1970s, he introduced me to William Copley (aka Cply), a friend of Marcel Duchamp, who was recovering from burns in Key West, Florida, while I was there on vacation. Copley was a functionary for Duchamp, gathering needed materials for the master artist’s last work, “Etant Donnés,” which was created in secret. Copley was necessary in perpetuating the ruse that Duchamp had “quit making art.”

So too, did Johnson use Robert Warner to run his errands in New York City, while Johnson secluded himself in the North Shore Long Island suburb of Locust Valley. Mugged the same day Warhol was shot, Ray took himself out of the scene, making occasional forays into the city, but relying on others like Warner to perpetuate his artistic presence, by asking him, for instance, to carry out mysterious deliveries to Jasper Johns.

Sequestered from the scene, using a third parties to intervene in his “performances,” Johnson continued his traditions of “nothings,” or “non-happenings,” which he labeled many of his public performances. If “happenings” were created situations to elevate one above the happenstance of existence , “nothings” blended activity with everyday life…nothing special.

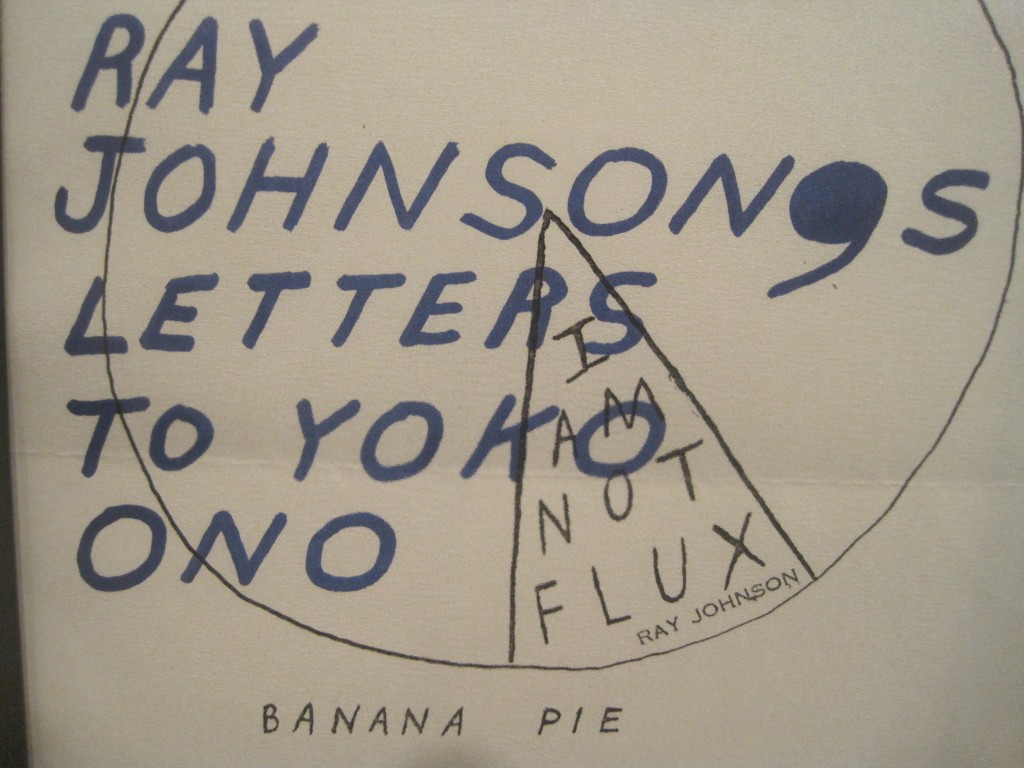

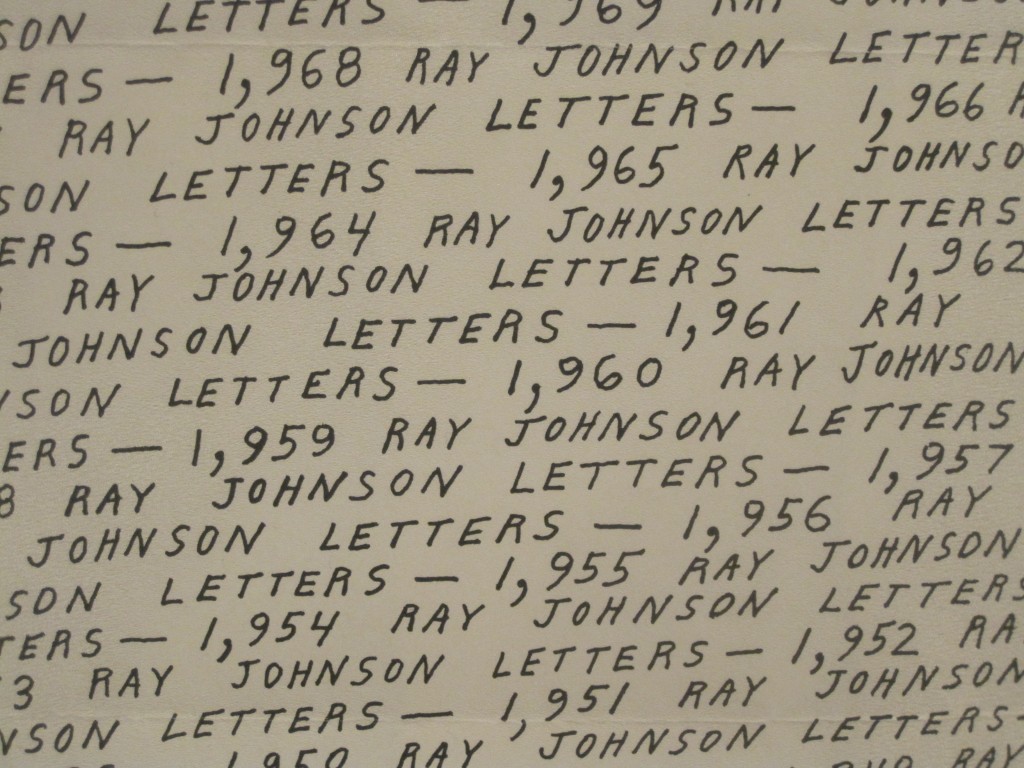

Johnson’s prime motivation was the aesthetic distribution of communication – not only through the postal system, with which he is associated as the Father of Mail Art – but by various mediums, including the telephone. Johnson persistent daytime telephone calls to Warner, caused Bob’s boss (an optician) to pull the plug on these workday performances. But by then, Bob had proved himself.

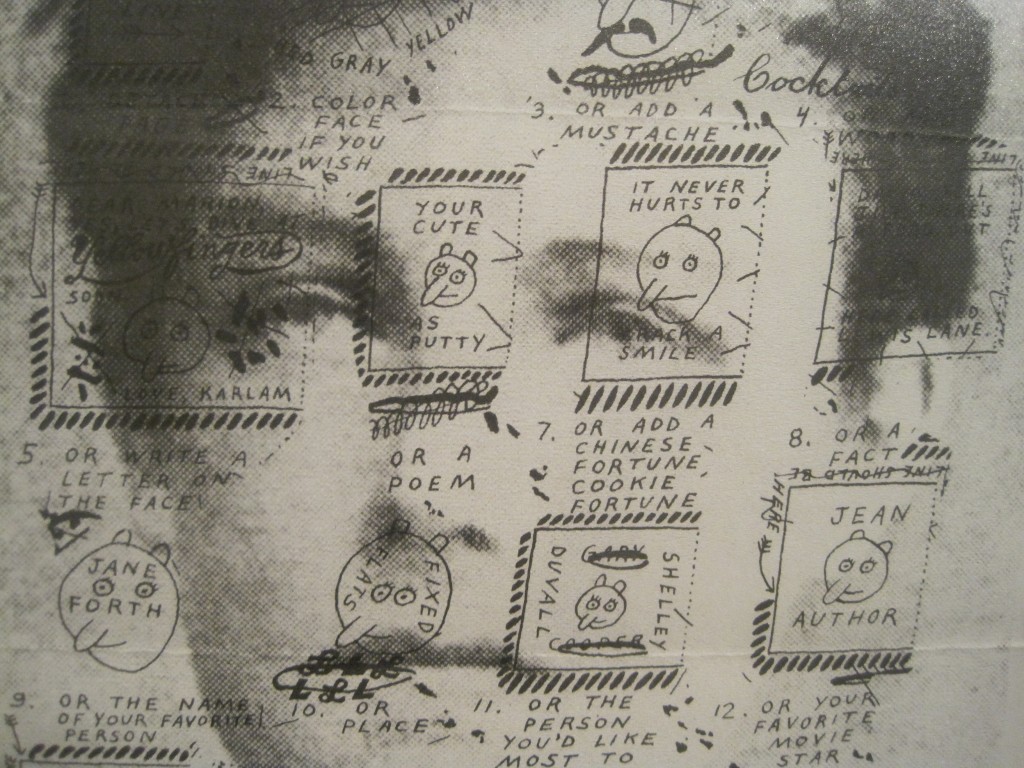

Johnson’s mailed works often included an “acid test.” They were freely given, but included calls for reciprocal response. Many of his mailings contained admonitions to “add and pass” or “add and return,” challenging the “purity quotient” of the receiver. Did the correspondent conform to instruction? Was the original photocopied first and then passed along? Was the admonition ignored? Bob Warner was subjected to a variety of these tasks, proving his trustworthiness.

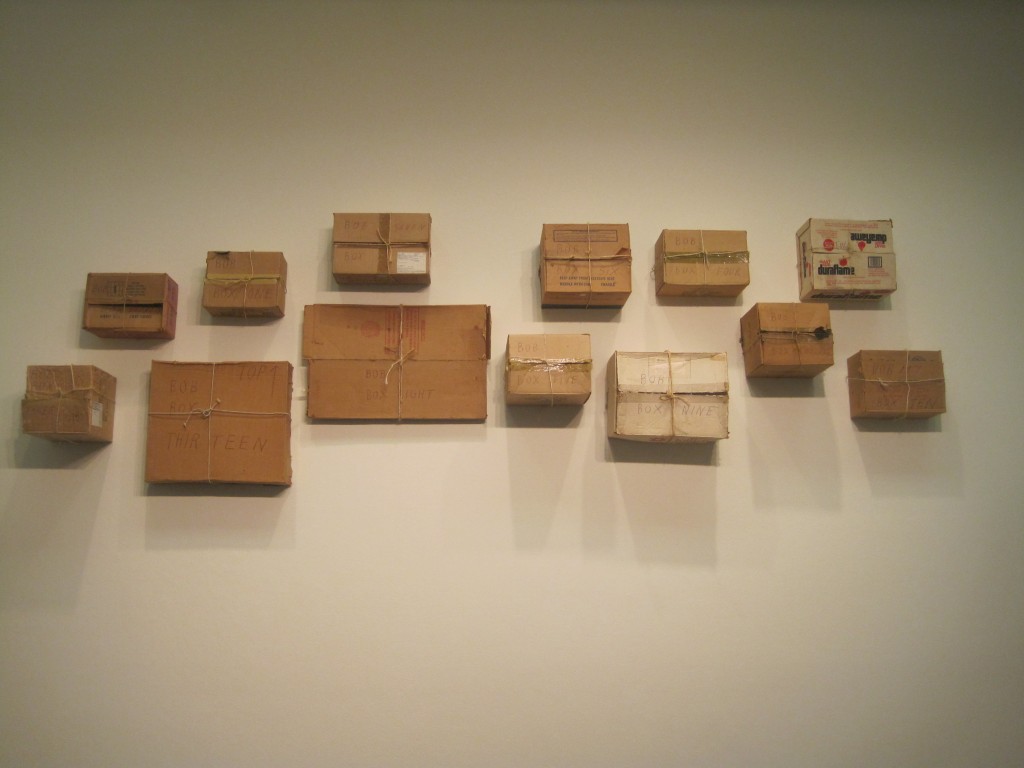

Having earned his stripes, Warner was given fifteen cardboard boxes stuffed with received mail and scores of addressed but unsent envelopes. Warner was instructed to forward two of the boxes to another party. For years, Warner kept the remaining thirteen boxes unopened and intact. In 2010, Esopus Magazine, sponsored a project through their gallery affiliate, whereby Warner would open the boxes in public and inventory the works.

After the exhibition, the newly inventoried works traveled to Philadelphia, with Berkeley the third stop of the tour. It was recommended to the Berkeley Museum by Dickran Tasjanian, a professor emeritus from the University of California, Irvine, recently retired to the Bay Area. The author of Skyscraper Primitives: Dada and the American Avant-Garde, 1910-1925, and Boatload of Madman: Surrealism and the American Avant-Garde, 1920-1950,” the scholar, an acquaintance of Warner, was aptly suited to appreciate Johnson’s difficult fit into these previous avant-gardes.

Tasjanian’s admiration was made easier by his and Johnson’s mutual appreciation of Joseph Cornell. Tashjian also authored, Joseph Cornell: Gifts of Desire, and Johnson counted Cornell among his circle of friends. A critical remark that Ray found amusing and often circulated was, “Johnson is to the letter, what Cornell was to the box.”

Both Warner and Tasjanian conducted gallery talks – Warner at the opening of the exhibition, and Tasjanian during its course. Both talks were well attended and served to inform the curious. Spread out on thirteen tables, the contents of the thirteen boxes needed some clarification.

At first sight, the items appear to be piles of flotsam and jetsam, with no apparent relationship to one another. The collection was not selected by Johnson, but generated by the Mail Art network. In deciphering the accumulation, there are clues for the initiated. For instance – a collection of belts, which related to Johnson’s fascination with snakes (and penises), and were in all likelihood, remnants of his 1970s era, “Spam Belt Club.” Johnson would often include instructions to his correspondents to send objects to an unwitting third party- for example, “Send slips to Lucy Lippard.” In turn, Johnson would often be the recipient of his correspondents peccadillos.

The boxes also contained items returned and embellished by correspondents as requested by Johnson, including a Johnson exhibition poster altered and returned by Bay Area artist William Wiley.

Also on exhibition are several of Johnson’s more formal collages, composed of wood or compressed cardboard, often bearing images first found in his mailings. Rarely shown during his lifetime, these works have gained increased recognition through their exhibition by the Ray Johnson Estate, administered by the Richard L. Feigen & Co., New York.

Despite the elegance of the framed collages, and their obvious appeal to collectors, the true importance of Ray Johnson lies in his preoccupation with the distribution of the artwork, in the process of which, he established a worldwide network, which continues to uphold his practice of freely circulated works, stimulating long distance aesthetic communication, friendship, and community.

Written by John Held, Jr.

Interview between Ray Johnson and John Held, Jr. linked here